Latest allegations of sexual assault show how the legal system discourage victims from coming forwar

What happens when assault survivors enter systems that are not designed to respond to their words or meet their needs.

Virginia’s Lt. Gov. Justin Fairfax is refusing to resign after denying charges by two women who have said that he sexually assaulted them.

The first woman to come forward was Vanessa Tyson, a politics professor at Scripps College. She initially contacted The Washington Post after Fairfax’s election in December 2017, alleging that Fairfax forced her to perform oral sex in 2004.

The Post stated it did not publish a story at that time because it “could not corroborate Tyson’s account or find similar complaints of sexual misconduct.”

So Tyson’s story did not make national headlines until this week, when it was first published by the conservative blog Big League Politics.

The second woman to come forward is Meredith Watson, who alleges Fairfax raped her while they were both students at Duke University in 2000. According to a statement written by her attorneys, Watson told a dean at the school about the rape, and the dean “discouraged her from pursuing the claim further.”

On Feb. 9, Fairfax asked the FBI to investigate their allegations. While it’s not clear that the FBI will investigate, the controversy raises important questions about how the legal system deals with cases of sexual assault.

I am a scholar of domestic and sexual violence, and my work has focused on analyzing the stories survivors share when they seek safety and hold perpetrators accountable for abuse. I’ve also studied what happens when the legal system encounters and processes these stories.

What I’ve found is a fundamental mismatch between what survivors disclose and what legal systems need to hear to take action.

Survivors and systems unaligned

Survivors of sexual assault expect to be able to share what they have experienced in a way that reflects how they have made sense of the event and its aftermath.

In contrast, courts want a report that is linear, providing an almost objective, dispassionate accounting of abuse with specific names, dates and “facts.” They want independent evidence of the abuse.

The problem is, acts of sexual and domestic violence rarely occur in front of other people, and survivors of sexual and domestic violence often have little external evidence of their assault other than their story.

The end result is that systems that are supposed to help are, in general, unable to adequately assess and respond to survivors’ stories.

For example, officers responding to cases of domestic violence often do not make arrests, especially in cases of sexual violence.

In an analysis of FBI data, my colleague Matthew Fetzer and I found that only 26 percent of cases of sexual domestic violence reported to the police resulted in an arrest (in comparison to 52 percent of cases of physical domestic violence).

This may be due to the intimate nature of sexual violence and the difficulty of proving sexual assault. As one woman who experienced sexual violence told researchers: “I was raped by my husband. There was no evidence except for bruises on the inside of my legs or the pain on my breasts, and you just can’t prove it.”

Many institutions and organizations make decisions based on stereotypes about survivors that rarely reflect their actual circumstances. That’s especially true with survivors who are not “good victims,” who are not white, middle-class women, and who do not have external documentation of their abuse.

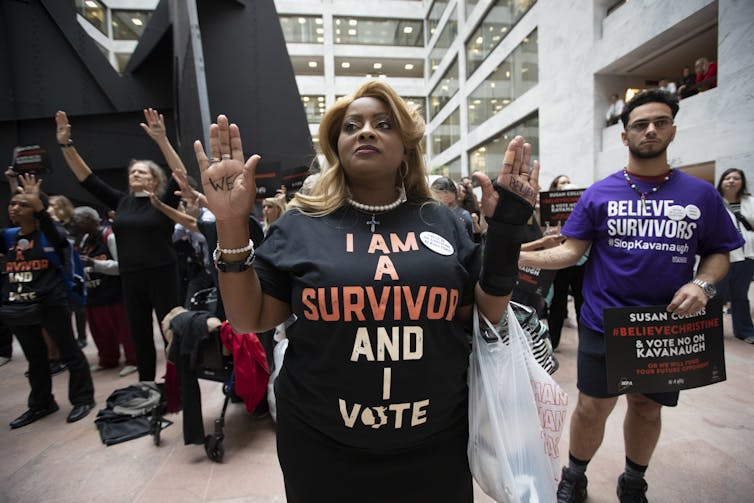

For many survivors – especially women of color, women reporting violence committed by perpetrators who hold power or women who experience sexual violence – it’s easier and safer to not report the abuse and pretend that the resulting trauma never happened.

To an outsider, the choice not to report an assault in the moment, or even years later, does not make sense.

They do not understand how survivors compartmentalize in order to survive or even thrive.

Many legal options for reporting sexual assault – such as calling the police – aren’t designed with survivors’ goals, needs and motivations in mind. So survivors do not see reporting as an option, and do not see the legal system as a resource.

Expecting a survivor to disclose their abuse to someone in the moment does not reflect current knowledge and theory about sexual and domestic assault.

Rethinking responses to violence

The Fairfax story is an opportunity to rethink how to help survivors of violence and how to hold perpetrators accountable for their actions.

In the right environment and with the right support, survivors will want to come forward, share their stories, and gain strength from doing so.

However, the legal system is an adversarial system with confusing and complex bureaucratic procedures and often untrained staff. As trauma scholar Dr. Judith Herman explains, “If one set out intentionally to design a system for provoking symptoms of traumatic stress, it might look very much like a court of law.”

Survivors are asked to recall specific details about their victimization that they have repressed in order to survive. As one advocate said to me in an interview, “They’re trying to forget what happened and here I am, asking them to write down, with as many details as they can, what they went through.”

How might we create a more responsive system?

First: Stop requiring survivors to narrate their abuse. It’s more detrimental than helpful, especially if we simply discount it as a “story” afterward.

If there is some form of external documentation, survivors should be able to provide that instead. If there is no external documentation, then the narrative should be elicited in a supportive environment of the survivor’s choosing, with trained staff available to help them better understand the kinds of information that judges and law enforcement need.

Second: People charged with listening and responding to survivors need to be educated about the dynamics of domestic and sexual violence. While some are, many do not fully understand the ways in which domestic and sexual violence affect survivors. It is impossible for them to hear and respond appropriately unless they understand those dynamics.

Finally: Explore what believing and supporting a survivor means.

While the words “I believe” and “I support” are critically important, they should not become buzzwords that replace actions. When you believe a survivor and decide to support that survivor, you must act. You must make hard, even unpopular, decisions.

You must work to adapt the system in order to uphold justice.

I believe. Period. I believe.

Editor’s note: This is an updated version of a story originally published on Oct. 12, 2018.

Alesha Durfee receives funding from the Center for Victim Research.

Read These Next

How the Emerald Isle shaped the Steel City – Pittsburgh’s rich Irish history

Long before Pittsburgh’s modern Irish celebrations existed, Irish immigrants helped shape the city…

I was teaching virtue and knowledge while lying on the side

While rationalizing deception is easy to do, developing the virtue of truthfulness is not.

As the Oscars approach, Hollywood grapples with AI’s growing influence on filmmaking

AI tools can now generate movie scenes, resurrect lost footage and replace entry-level jobs – forcing…