Democrats court rural Southern voters with Stacey Abrams' State of the Union response

The South is changing, with more Asian and Latino immigrants moving in and diversifying a region that was once black and white. Stacey Abrams knows that Democrats can win these rural voters.

In a brief, direct and optimistic speech about fighting immigrant scapegoating, racism and voter suppression, Stacey Abrams celebrated diversity in her Democratic rebuttal to Donald Trump’s divisive 2019 State of the Union address.

“We will create a stronger America together,” she said.

Abrams is the first African-American woman to deliver a State of the Union response in the 53-year history of this tradition. She is the first black woman to be nominated by a major party to run for governor. Before that, she was the first African-American ever to serve as House minority leader in the Georgia General Assembly.

Her State of the Union response has increased speculation that she is a rising political star with a bright future in the Democratic Party.

By choosing Abrams to give the State of the Union response, Democrats were clearly reaching out to African-Americans and women, a key base for the party.

But Abrams’ speech also spoke to an often-overlooked constituency the Democratic Party may not have even thought about when they picked her. It’s a constituency Abrams has already cultivated: rural Southerners of color.

Abrams campaigned in both urban and rural counties last year, defying the logic of a Democratic Party that tends to court big city voters while leaving rural Americans to be won over by Republicans like Donald Trump.

Forgotten Southerners

I have been studying minority politics in the South for over 20 years.

The rural South is home to about 90 percent of America’s entire black rural population, and politics in this region have long been defined by black and white polarization. The South was a Democratic stronghold until the civil rights movement, and Democrats know they can’t win national office without winning here.

But the South – both urban and rural – is changing. In recent decades, a large number of Asian and Hispanic immigrants have settled in Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina and other southern states, bringing greater demographic and political diversity to this formerly black-and-white region.

Chinese immigrants first came to rural southern areas like the Mississippi Delta after the Civil War, so Asian-Americans have deep roots in the South. But between 2000 and 2010, the population of Asian-Americans in the South grew 69 percent, to over 3.8 million, largely due to the region’s many job opportunities and affordable housing.

The South’s Hispanic population has grown by 70 percent in recent years, surpassing 2.3 million people in 2010, when the last U.S. Census was taken. Many of these individuals have settled in rural communities, filling agricultural and other jobs and sending their children to public school.

Racial and ethnic minorities now make up over 20 percent of the entire rural population in ten southern states, from Florida to Virginia.

Democrats’ rural base

Democrats can and should court these communities if they want to win in the South. Stacy Abrams knows that. She even opened her speech wishing viewers a “happy Lunar New Year,” a nod to Chinese-Americans.

The overwhelming majority of black rural Southern residents are Democrats. Asian-American and Latino voters across the nation lean Democratic.

Abrams won big in rural northern Georgia, in places like Calhoun County, which in addition to being heavily African-American has one of the highest Latino populations in the state outside Atlanta.

Abrams benefited not just from rural votes but also from their turnout.

In predominantly black and rural Washington County, Georgia, where Abrams received 69 percent of the primary vote, the turnout rate nearly doubled from 2014. From the first days of her campaign, Abrams targeted rural voters, bringing them into the electoral process.

She did the same thing for the Democratic Party in the general election.

Voter suppression

Abrams’ State of the Union response also focused on an issue that has marred Southern elections for over a century: minority voter exclusion.

“Let’s be clear,” she said. “Voter suppression is real. From making it harder to register and stay on the rolls to moving and closing polling places, to rejecting lawful ballots, we can no longer ignore these threats to democracy.”

Abrams’ focus on voter suppression as a candidate was appealing to people of color, some of whom learned late in the 2018 campaign season that many of their ranks had been purged from voting rolls.

Some 107,000 people were removed from Georgia’s voter registration list because they hadn’t voted in previous elections. Another 50,000 applications to vote submitted by black, Asian and Latino Georgians were invalidated because of Georgia’s “exact match” law, which requires that the name on voter registration applications match exactly the information already on file with the government.

Voting rights groups said the law amounted to voter suppression, and blamed Abrams’ narrow loss on fraud by then-Secretary of State Brian Kemp, her opponent. Kemp denied the accusations and said his office was working to ensure “election integrity.”

Georgia’s exact match law disproportionately affects immigrants who had recently become citizens as well as Asian-Americans, who in 2016 were six times more likely to have their applications rejected because the names they registered to vote with differed minutely from their names on other identification forms.

Because of her political accomplishments, charisma – and, now, her national name recognition – Abrams’ importance for the Democratic Party goes beyond her obvious appeal to African-Americans and women.

If Democrats want to win big in 2020, they’ll need Stacey Abrams.

Sharon Austin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Public defender shortage is leading to hundreds of criminal cases being dismissed

There are never enough lawyers to provide indigent defense, but the situation has gotten worse since…

Welcome to the ‘gray zone’ − home to nefarious international acts that fall short of outright confli

Nations are becoming adept at provocations that fall in the area between routine peacetime actions and…

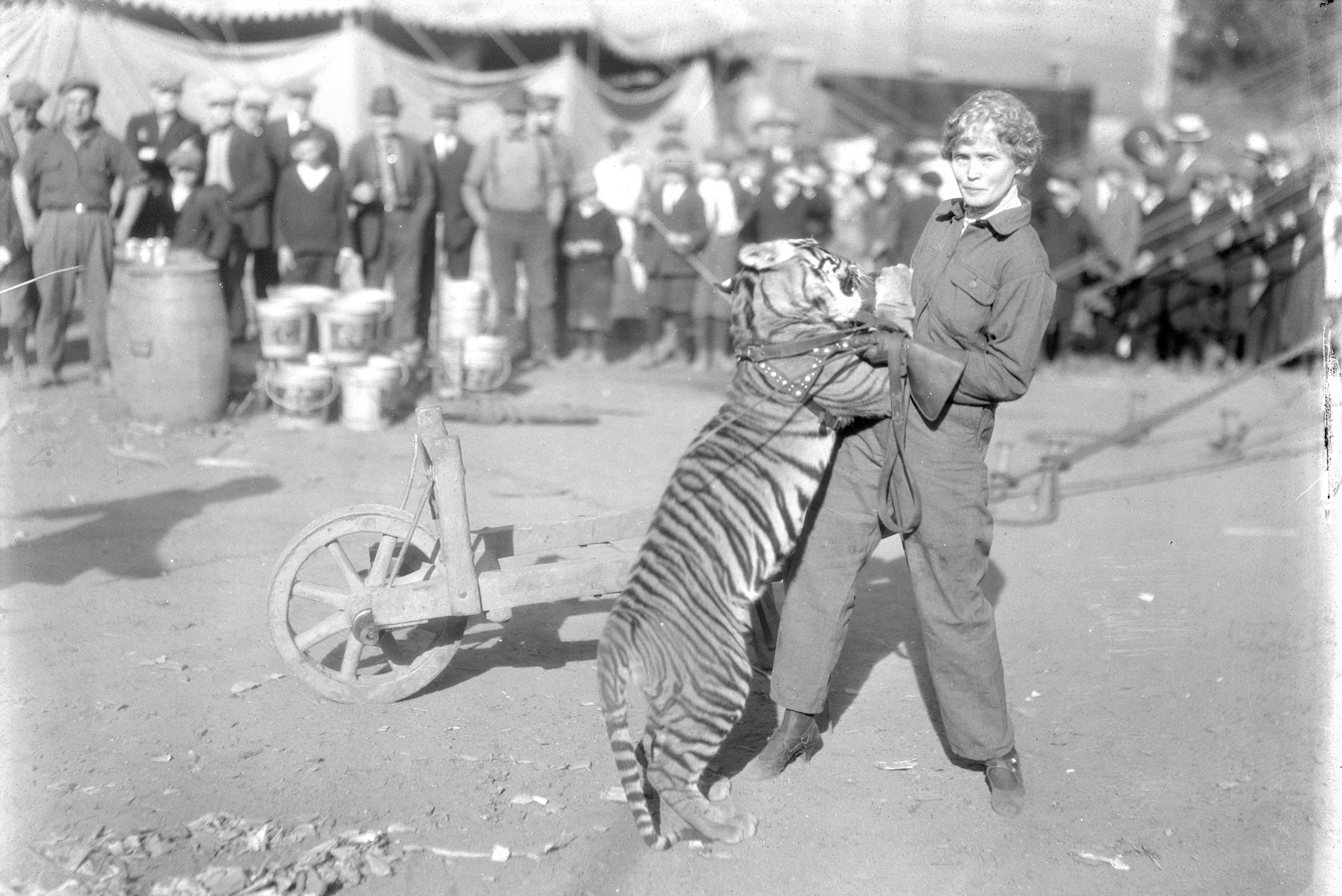

The inspiring and tragic story of Mabel Stark, America’s most famous female tiger trainer

Long before Joe Exotic became Tiger King, Mabel Stark reigned as Tiger Queen.