Personal diplomacy has long been a presidential tactic, but Trump adds a twist

Meeting with heads of state has become routine for presidents, but Trump's way with words and gestures rattles many in the diplomatic community. The biggest concern is his sweet talk to dictators.

President Donald Trump plans a second meeting with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un in February in what will be another example of Trump’s personal diplomacy efforts.

In September, Trump told the crowd at a rally that he “fell in love” with Kim after the two exchanged letters. Many were critical of the statement, including allies of the president like Sen. Lindsey Graham. While Trump later admitted that his profession of love was “just a figure of speech,” the comment puts a spotlight on his relationships with foreign leaders.

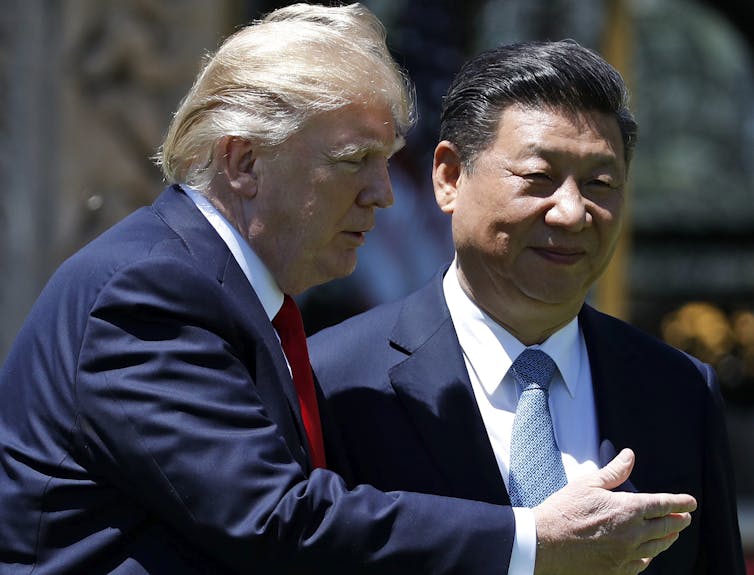

In Trump’s first two years in office, he’s met with many world leaders both at home and abroad. Several of these interactions grabbed headlines, often for the wrong reasons: aggressive handshakes, shoving, insulting allies, and what some critics consider fawning love fests with dictators like Kim and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

With such a record, would American interests be better served if Trump stayed away from world leaders? The truth is that even if the answer were yes, he couldn’t. The president is diplomat-in-chief. Personal diplomacy is part of the job.

I study personal diplomacy and I know the centrality of the practice to the presidency in the post-WWII era. Despite what his critics say, Trump’s use of personal diplomacy is a continuation of past presidential practice. It’s his style and approach that break from past tradition.

Personal diplomacy is part of the presidency

This wasn’t always the case. Not until Franklin D. Roosevelt did personal diplomacy become increasingly common in the presidency. Technological advancements in communication and travel, America’s rise to global preeminence, the growth of presidential power, and increasing domestic incentives made the practice appear attractive and often necessary to White House occupants.

Professional diplomats have long complained about political leaders engaging in personal diplomacy. Writing in 1939, British diplomat Harold Nicolson put it like this: Frequent meetings between world leaders “should not be encouraged. Such visits arouse public expectations, lead to misunderstanding and create confusion.”

Professional diplomats are generally better informed than political leaders on international issues. They also are experienced negotiators, possess linguistic expertise and are knowledgeable of diplomatic protocol. They are also usually less influenced by domestic politics. They tend to stay out of the media spotlight and work behind the scenes.

But history provides us with many examples of the value of leader-to-leader diplomacy. Franklin Roosevelt’s connection with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill played a central role in the Allied victory during WWII. The bond between Jimmy Carter and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat was crucial to Egyptian-Israeli peace. And Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev’s relationship was key to the end of the Cold War.

Presidents themselves have recognized the importance of leader-to-leader diplomacy. George W. Bush wrote in his memoir, “I placed a high priority on personal diplomacy. Getting to know a fellow world leader’s personality, character, and concerns made it easier to find common ground and deal with contentious issues.”

Dangers lurk

But there are risks as well.

Leaders don’t always get along. Miscalculation and tension may be as likely as understanding and cooperation.

In 1961, U.S.-Soviet relations went from bad to worse after John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev met. Khrushchev came away thinking the president was weak and inexperienced. Within months, the Soviet leader ordered the building of the Berlin Wall. The following year, Khrushchev put nuclear missiles in Cuba capable of reaching almost every corner of the continental United States.

George W. Bush thought he could trust Russian leader Vladimir Putin because he “looked the man in the eye” and “was able to get a sense of his soul.” But by the end of his presidency, it was clear that Bush had seriously misjudged the Russian leader.

Trump’s approach

In his two years in office, Trump has shown himself both following in his predecessors’ personal diplomacy footsteps but also breaking from established norms.

As candidate Trump, he boasted that he would get along with Putin. And since becoming president, he has continued to promote his personal relationships with world leaders.

This is normal presidential behavior. Where Trump differs from his predecessors is in the relationships he promotes and the way he approaches personal diplomacy.

One of the most striking things about Trump’s personal diplomacy is his praise of dictators. While past American presidents also sought to form personal bonds with unsavory leaders, none so publicly embraced and praised brutal authoritarians such as Kim, Putin and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman as Trump has done.

This has a cost. Personal diplomacy is a form of “theater.” It sends signals to domestic and international audiences. The leaders a president decides to meet with, praise or attack is a statement of American values and policy. By effusively embracing dictators, Trump’s personal diplomacy is at odds with traditional American foreign policy, and critics argue that it emboldens dictators.

Trump also differs from past presidents by appearing indifferent to the risks of personal diplomacy. “You have nothing to lose and you have a lot to gain,” he said.

Personal diplomacy is a tool presidents use to advance American interests. And because of the risks, careful preparation and a clear strategy are vital.

But Trump is impulsive and prone to rely on “touch” and “feel.”

Politics is deeply personal for him. While disagreement is a natural part of international politics, he often views it as a personal affront. Before he fell in “love” with Kim Jong Un, he called the North Korean dictator a “madman” and mocked his height and weight.

Trump has even attacked allied leaders. When Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau stated his country wouldn’t be pushed around, the president felt betrayed and lashed out, calling Trudeau “very dishonest and weak.”

Leader-to-leader diplomacy is inherently personal. But presidents are best served when they don’t take it too personally. Former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger once said, “America has no permanent friends or enemies, only interests.” So even if leaders form personal bonds, it doesn’t mean two nations will always agree. And that’s OK. It’s a natural part of international relations, not a personal insult to the president.

When presidents engage world leaders, the stakes are raised and mistakes amplified. So a clear assessment of the risks and benefits of personal diplomacy is essential. As former Secretary of State Dean Acheson cautioned, “When a chief of state or head of government makes a fumble, the goal line is open behind him.”

Tizoc Chavez does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Why US third parties perform best in the Northeast

Many Americans are unhappy with the two major parties but seldom support alternatives. New England is…

Detroit was once home to 18 Black-led hospitals – here’s how to understand their rise and fall

In the early 20th century, Detroit’s Black medical professionals created a network of health care…

From moral authority to risk management: How university presidents stopped speaking their minds

Nearly 150 universities and colleges have adopted institutional neutrality pledges since 2023.