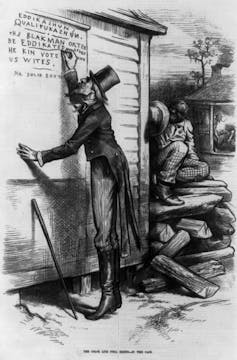

Georgia election fight shows that black voter suppression, a southern tradition, still flourishes

Georgia's refusal to process 53,000 voter registrations, mostly filed by African-Americans, is the latest in a long history of black voter suppression in the South, from poll taxes to literacy tests.

Georgia’s Republican Secretary of State Brian Kemp has been sued for suppressing minority votes after an Associated Press investigation revealed a month before November’s midterm election that his office has not approved 53,000 voter registrations – most of them filed by African-Americans.

Kemp, who is running for governor against Democrat Stacey Abrams, says his actions comply with a 2017 state law that requires voter registration information to match exactly with data from the Department of Motor Vehicles or Social Security Administration.

The law disproportionately affects black and Latino voters, say the civil rights groups who brought the lawsuit.

As a scholar of African-American history, I recognize an old story in this new electoral controversy.

Georgia, like many southern states, has suppressed black voters ever since the 15th Amendment gave African-American men the right to vote in 1870.

The tactics have simply changed over time.

Democrats’ southern strategy

With black populations ranging from 25 percent to nearly 60 percent of southern state populations, black voting power upended politics as usual after the Civil War.

During Reconstruction, well over 1,400 African-Americans were elected to local, state and federal office, 16 of whom served in Congress.

Loyal to President Abraham Lincoln, whose Emancipation Proclamation sounded the death knell for slavery, black Americans flocked to the Republican Party. Back then, it was the more liberal of the United States’ two mainstream political parties.

Southern Democrats fought back, using both violence and legislation.

White paramilitary groups like the Ku Klux Klan and White Leagues threatened black candidates, attacked African-American voters, pushed black leaders out of office and toppled Republican governments.

After establishing single-party control over the South, white Democrats in the late 1800s instituted a poll tax, making voting too expensive for former slaves and their descendants.

“White primaries” excluded blacks from choosing candidates in primary elections.

These attacks proved effective. Between 1896 and 1904, the number of black men who voted in Louisiana plummeted from 130,000 to 1,342.

After North Carolina U.S. Rep. George White retired, in 1901, the South would send no African-Americans to Congress until the 1972 election.

Voter suppression in Jim Crow Mississippi

In the early 20th century, many black Americans voted with their feet, migrating north and west.

Around the same time, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal – which instituted racial quotas in hiring for federal public work projects and included policies aimed at reducing inequality – was shifting northern black voters’ allegiance to the Democratic Party.

Black voters in northern cities began putting African-American Democrats into congressional office.

But they did not give up on the South, pressing the Supreme Court to reaffirm voting rights in the 1944 case Smith v. Allwright, which prohibited white-only primaries.

But black voter suppression remained deeply entrenched in the South. Several states required new voters to complete literacy tests before they could cast a ballot. In the 1880s, 76 percent of southern blacks were illiterate, versus 21 percent of whites.

Strategies for excluding black voters evolved along with federal law.

In reaction to Brown v. Board of Education, which in 1954 overturned “separate but equal” segregation laws, Mississippi in the same year modified its poll test. It asked voters to interpret a section of the state’s constitution, authorizing county registrars to determine whether the applicant’s answer was “reasonable.”

Virtually all African-Americans, regardless of education or performance, failed.

Within a year, the number of blacks registered to vote in Mississippi dropped from 22,000 to 12,000 – a mere 2 percent of eligible black voters.

Political violence – including the 1955 attempted assassination of voting rights activist Gus Courts and murder of George W. Lee – accompanied the legal restrictions, showing the cost of black political independence.

Fighting for the vote

Activists were not deterred. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Congress of Racial Equality continued to wage grassroots voter registration campaigns and fight for official representation in the Democratic Party.

In 1964, a new political party, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, was founded to welcome “sharecroppers, farmers and ordinary working people.”

The Freedom Democratic Party elected 68 delegates to attend the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey, hoping to transform the all-white Mississippi delegation.

Trying to broker a deal, national Democratic leaders extended Mississippi’s Freedom Democrats two nonvoting at-large seats at the convention – a minor concession that led most white Mississippi party members to walk out in protest.

Freedom Democrats rejected the two seats as tokenism, holding a sit-in on the convention floor in Atlantic City to highlight the lack of black political representation.

Black voters make gains

Over time, the civil rights movement sparked a political shift that dramatically changed the U.S. electorate.

The 24th Amendment outlawed poll taxes in 1964, abolishing a major barrier to black enfranchisement in the South. Literacy tests, too, were restricted, under the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

The Voting Rights Act also established federal oversight of voting laws to ensure equal access to elections, particularly in the South.

By the early 21st century, African-Americans constituted a majority of the registered Democrats in Deep South states from South Carolina to Louisiana. They turn out in high numbers and have been key voters for getting Democrats into office in the conservative-dominated South.

Voter suppression today

Over the past decade, Republican lawmakers have chipped away at the last century’s advances, enacting voter ID laws that make it harder to vote.

Claiming they seek to deter election fraud, some 20 states have restricted early voting or passed laws requiring people to show government ID before voting.

Voter identification laws have hidden costs, research shows.

Getting a government ID means traveling to state agencies, acquiring birth certificates and taking time off work. That puts it out of reach for many, a kind of 21st-century poll tax.

Federal and state courts have overturned such laws in some states, including Georgia, North Carolina and North Dakota, citing their harmful effect on African-American and Native American voters.

But the Supreme Court in 2008 deemed Indiana’s voter ID law a valid deterrent to voter fraud.

Perhaps most damaging to black voters was a 2013 Supreme Court decision that weakened the Voting Rights Act.

Shelby County v. Holder ended 48 years of federal oversight of southern voting laws, concluding that the requirement relied on “40-year-old facts that have no logical relation to the present day.”

Current events show that voter suppression is hardly a thing of the past.

From Georgia’s voter registration scandal to gerrymandered districts that dilute minority voting power, millions may be shut out of November’s midterms.

Frederick Knight does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…

Why US third parties perform best in the Northeast

Many Americans are unhappy with the two major parties but seldom support alternatives. New England is…

Abortion laws show that public policy doesn’t always line up with public opinion

Polls indicate majority support for abortion rights in most states, but laws differ greatly between…