Why is it so hard to get an accurate vote count?

There are different ballots, voting machines, registration and eligibility requirements and procedures for counting votes across the country. That's a recipe for occasional confusion and miscounts.

In Kansas this past August, vote totals in the Republican primary for governor fluctuated by more than 100 votes over the course of a few days, and the winner – Secretary of State Kris Kobach – wasn’t declared until a week after the vote.

In Virginia, a hotly contested battle last year for the commonwealth’s House of Delegates first gave the race to the Republican by 10 votes, and after a recount, the Democrat led by one vote. A court later decreed the election a tie, and it was decided in favor of the Republican by a random drawing.

Why are the vote totals for many political offices so hard to nail down?

Shouldn’t it be easy to count ballots, the way they do in Britain, for example?

Local control

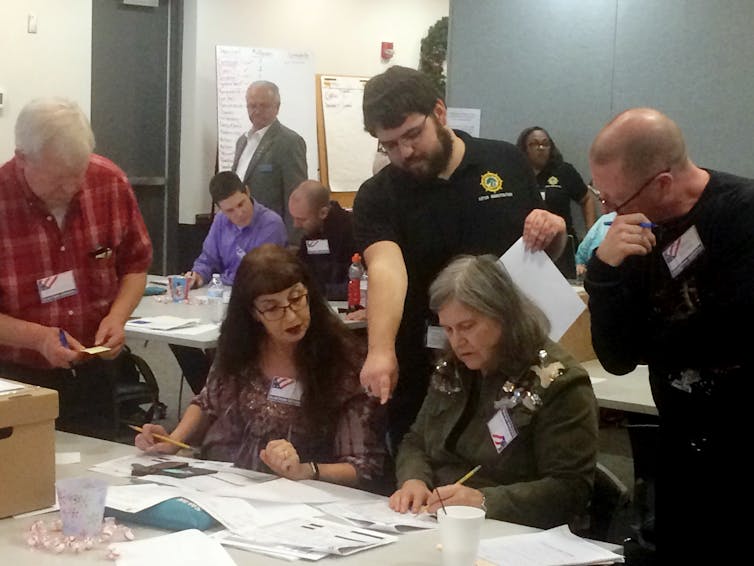

One major explanation is that we don’t really have a national election like they do in Britain. And with each state and local government running elections and counting ballots, often with the help of citizen volunteers, mistakes can happen.

In the United States, we have a series of simultaneous state and local elections held at around the same time. There is no national agency that administers American elections; they are overseen by more than 10,000 local jurisdictions.

This means that there are different ballots, different voting machines, different registration and eligibility requirements, and different administrative procedures for counting votes all across the country. That’s a recipe for occasional confusion and miscounts.

Goal is same; methods aren’t

Sometimes the technology itself can confuse voters and cause them to make errors when voting. That was the case with the “butterfly ballot” used in Palm Beach County in the 2000 election, whose “hanging chads” made it hard to determine for whom the ballot was cast.

Shifts to new technology can produce problems and then errors in vote counts, as my colleagues and I showed in research supported by the National Science Foundation.

The cost of holding elections is paid from local tax revenue, so local governments have a disincentive to invest in upgrading voting systems. Since providing police and fire service, a good education and picking up garbage all have a higher priority than administering elections, financial support for election administration is often a low priority.

Ultimately, the secretary of state in each of the 50 states (or the head of an election division within that office) is responsible for certifying the result of the election for each office, property tax or bond issue, or proposition appearing on the ballot. It’s in that office that conflicting vote totals ultimately get reconciled.

But how they get to a certified result varies by location as well.

Changes in how votes are cast

Voting used to take place on a single day. A voter had to show up in person to cast a ballot.

In 1993, in the interest of convenience and increasing turnout, Congress passed the National Voter Registration Act, also known as the Motor Voter Act. The legislation allows registration for voting at the same time a person applies for a driver’s license or renewal, as well as other registration opportunities when interacting with state and federal government agencies.

Turnout in the United States is lower than in most democracies, and a number of procedures have been adopted in various states to allow people to use absentee ballots, cast votes at early voting sites, and even to obtain provisional ballots for people who show up to vote in person but whose eligibility is questioned.

All of these parameters vary by location. For example, early voting can start as much as 46 days before Election Day in some states, like Minnesota and Illinois, while states like Michigan do not allow it at all.

In many states, different kinds of ballots are counted at different points in time.

In-person ballots are often counted on election night, and absentee ballots are counted then or shortly thereafter.

Provisional ballots, which are used when there are questions about a voter’s eligibility, are held confidentially in envelopes with signatures and other identifying information. They have to be checked for eligibility back in a local clerk’s office and may not be counted for a day or two.

Military ballots mailed in from overseas will be counted as long as they are postmarked by Election Day, but they could take several days to get to the local office.

Because of this complexity, election administrators must have a set of procedures in place to ensure the integrity of the voting system.

Once the votes are in

In each precinct on election night, there is an audit process that the local election director oversees to insure the integrity of the ballots and the count. An initial count is made in a series of steps. Here is what that looks like:

After the ballots are first counted in each precinct, often by volunteer poll workers with various levels of experience and training, those totals are transmitted in person to a secure location. Then, totals are added up for the ward, city, county and the state level.

The ballots themselves – or devices with ballot totals like voting machine cartridges – are brought by precinct workers to a secure location. Sometimes, because of human error, a small number of ballots – typically one precinct or less – may be temporarily misplaced: for example, one ballot box or one cartridge. When they are recovered, the initial vote count will be adjusted. In all of these ways, a final preliminary vote count is generated.

After the initial vote tabulation, there is a period when the results can be challenged for various reasons and a recount requested.

In some jurisdictions, a recount may be mandatory when the winning margin falls within a certain small range.

All of these procedures must take place in a period from 30 days after the election to when the state legislature next convenes and the secretary of state certifies the results as final. The vote totals again have a chance of changing – typically by a small amount – but hardly anyone pays attention to these final adjustments.

One more variable

One final note: For decades the Associated Press provided county-level vote totals to news agencies on election night.

But starting this November, there will be two major exit poll operations and associated systems for collecting and disseminating the county-level votes.

The Associated Press will partner with Fox News, while Edison Research, which has been responsible for the National Election Pool, the exit poll conducted for a combine of major news organizations since 2004, will tabulate raw vote totals as well.

Because Edison Research will be new at providing vote totals, it could encounter some technical difficulties in collecting and disseminating the data. There could also be some variability in the speed with which the vote totals are released.

As a result, conflicting vote tabulations could appear in the 2018 general election. Remember – these are only preliminary vote counts for the benefit of news organizations, not the certified results.

Michael Traugott received funding from the National Science Foundation to study voting technology.

Read These Next

How a 22-year-old George Washington learned how to lead, from a series of mistakes in the Pennsylvan

Washington’s fundamental character as a military leader was forged in the Ohio River Valley, where…

Local governments provide proof that polarization is not inevitable

Partisan debates are less heated at the local level, providing lessons that might help calm the waters…

As Jeff Bezos dismantles The Washington Post, 5 regional papers chart a course for survival

Other billionaires who own newspapers are doing a better job, a journalism professor explains.