Kavanaugh confirmation could spark a reckoning with system that often fails survivors of sexual abus

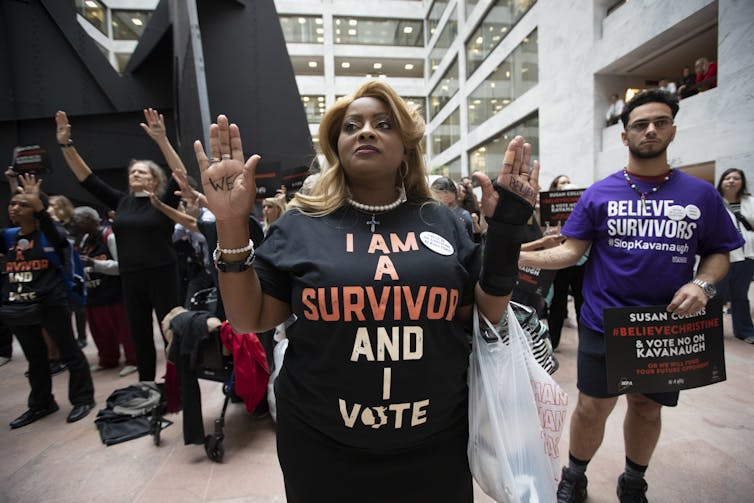

The testimony of Christine Blasey Ford in the Kavanaugh nomination hearings showed what happens when abuse survivors enter systems that are not designed to respond to their words or meet their needs.

After voting to confirm Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, Sen. Joe Manchin said that he made his choice even though he supported survivors of sexual abuse and believed that “we have to do something as a country” about sexual violence.

“I’m very much concerned… with the sexual abuse that people had to endure,” he said. “But I had to deal with the facts I had in front of me.”

The testimony of Dr. Christine Blasey Ford, and Kavanaugh’s confirmation despite that testimony, is a prominent example of what happens when abuse survivors engage with systems that were never designed to respond to their words or meet their needs.

Although few survivors testify in front of the Senate, the process by which Ford was forced to tell her story, and reaction of senators to that story, is strikingly similar to what abuse survivors undergo every day in civil and criminal courts.

I am a scholar of domestic violence, and my work has focused on analyzing the stories survivors share when they seek safety.

I’ve also studied what happens when the legal system processes these stories.

What I’ve found is a fundamental mismatch between what survivors disclose and what legal systems need to hear to take action.

Victims and systems unaligned

Legal institutions ask survivors to explain why they need legal protection, to tell their story of abuse. But, as noted by scholars Shonna Trinch and Susan Berk-Seligson, “What is needed by those whose job is to listen to them is a report, not a story.”

Courts want a report that is linear, providing an almost external accounting of abuse with specific names, dates and “facts.” Survivors expect to be able to share what they have experienced in a way that reflects how they have made sense of the event and its aftermath.

The end result is that we have systems that are supposed to help, but in general are unable to adequately assess and respond to survivors’ stories.

My research shows that survivors who disclose their abuse often hear initial statements of support and belief. Those statements are quickly negated by a “but” and an explanation of why someone will continue to act as if that story had never been told.

How did we end up with this system?

Many scholars, including Kimberlé Crenshaw, argue that institutions, including the legal system, design policies based on stereotypes about survivors that rarely reflect their actual circumstances. That’s especially true with survivors who are not “good victims” or who are not white, middle-class women who have external documentation of physical abuse.

This explains how what appears to be neutral system can produce different outcomes for people based on the intersections of gender, race, sexuality, age, citizenship status and other aspects of social identities.

For example, using victim advocates from a prosecutor’s office or police department to assist survivors filing for protection orders that would keep them safe from their abusers appears to be an effective use of resources.

But many abuse survivors have legal problems themselves or mistrust the legal system. They may not want to report the violence they’ve experienced because they could become the target of immigration enforcement or child protective services.

For many survivors, it’s easier and safer to not report the abuse and pretend that the resulting trauma never happened.

Puzzles in the aftermath

To an outsider, the choice not to report in the moment, or even years later, does not make sense.

They do not understand how survivors compartmentalize in order to survive or even thrive. They do not see that survivors evolve complex ways of coping, such as Ford’s insistence on constructing double front doors at her home so she’d be able to escape through one if the other was blocked.

The legal system’s rules of evidence, evidentiary requirements and statutes of limitations all reflect this.

What I’ve found in my research is that the legal system wants short, brief reports that focus on legally relevant acts of abuse, contain specific information and include supplemental documentation.

Few survivors can craft those types of narratives unassisted.

And many survivors – especially those who are of color, are poor or do not have U.S. citizenship, and who are not heterosexual – do not see institutions like the legal system as a resource.

Those institutions aren’t designed with their goals, needs and motivations in mind. When they witness events like the confirmation hearing, where a woman with education and privilege discloses sexual violence and nothing happens, how can they be expected to entrust their own narratives of abuse to others?

.

Speaking up

Ruth Bader Ginsburg said that “I’m dejected, but only momentarily, when I can’t get the fifth vote for something I think is very important. But then you go on to the next challenge and you give it your all. You know that these important issues are not going to go away. They are going to come back again and again. There’ll be another time, another day.”

For some survivors, today, in the aftermath of Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony, is finally that day. They are filling out protection order petitions, calling the police, reaching out for help.

But in some cases, they will be denied an order, the abuser will not be sanctioned or they themselves will be mistakenly arrested instead of, or along with, their abuser. In the toughest cases, like that of Melanie Edwards in Washington state, they will be killed by their abusers.

The United States should rethink how to help survivors of violence and how to sanction perpetrators.

Helping or hurting?

In the right environment and with the right support, survivors will want to tell their stories and will be empowered and validated by that retelling.

However, the legal system is an adversarial system with confusing and complex bureaucratic procedures and often untrained staff. As trauma scholar Dr. Judith Herman explains, “If one set out intentionally to design a system for provoking symptoms of traumatic stress, it might look very much like a court of law.”

Survivors are asked to recall specific details about their victimization that they have repressed in order to survive. As one advocate said to me in an interview, “They’re trying to forget what happened and here I am, asking them to write down, with as many details as they can, what they went through.”

How might we create a more responsive system?

First: Stop requiring survivors to narrate their abuse. It’s more detrimental than helpful, especially if we simply discount it as a “story” afterward.

If there is some form of external documentation, survivors should be able to provide that instead. If there is no external documentation, then the narrative should be elicited in a supportive environment of the survivor’s choosing, with trained staff available to help them better understand the kinds of information judges and law enforcement need.

Second: People charged with listening and responding to survivors need to be educated about the dynamics of domestic and sexual violence. While some are, many do not fully understand the ways in which domestic and sexual violence impact survivors. It is impossible for them to hear and respond appropriately unless they understand those dynamics.

The confirmation hearings, and the responses to Ford’s testimony, underscored this idea. While the remarks of some senators after her testimony reflected that they understand that they should “support” and “believe” survivors of violence, they also showed they were not informed about how survivors act in response to and process sexual trauma.

It’s as if they were saying: I believe, but I don’t understand, so your story does not exist for me in that it does not force me to act or impact my vote.

Finally: Explore what believing and supporting a survivor means.

While the words “I believe” and “I support” are critically important, they should not become buzzwords that replace actions. When you believe a survivor and decide to support that survivor, you must act. You must make hard, even unpopular, decisions.

You must work to adapt the system in order to uphold justice.

I believe. Period. I believe.

Alesha Durfee receives funding from the National Institute of Justice.The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Justice.

Read These Next

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…

Drug company ads are easy to blame for misleading patients and raising costs, but research shows the

Officials and policymakers say direct-to-consumer drug advertising encourages patients to seek treatments…

Bad Bunny says reggaeton is Puerto Rican, but it was born in Panama

Emerging from a swirl of sonic influences, reggaeton began as Panamanian protest music long before Puerto…