Resistance is a long game

The 'resistance' to the Trump administration has many forms, from grassroots organizing to making music. But a historian of 20th-century Germany asks whether opposing Trump is a real resistance.

What does resistance really look like?

In the United States, at least since November 2016, the idea of resistance seems to reflect a broadly imagined popular opposition to the presidency of Donald Trump.

At best that sentiment shows up in thousands of grassroots organizations that have taken to the streets or organized on behalf of local political candidates. At worst it functions as little more than the latest lifestyle brand.

Since The New York Times published an op-ed by an anonymous author declaring “I Am Part of the Resistance Inside the Trump Administration,” many commentators have weighed in about the extent to which the actions described in the piece rise to the level of “resistance.”

The anonymous op-ed writer, who claims membership in the resistance, projects an expectation, or perhaps a hope, that he will be able to claim, after the political “wars” over Trump have ended, a position of admirable rectitude.

Once the Trump administration comes to an end, this “quiet resistance” will no longer be necessary, since, as the op-ed writer asserts, these actions will have “preserved America’s democratic institutions.” Politics will be back to normal. Resistance, in this formulation, rights what is wrong.

As a historian of everyday life in 20th-century Germany, I approach the question of resistance with a rather different perspective, one that sees collaboration and resistance as two sides of the same coin. Even ardent anti-Nazis could act in ways that abetted the exercise of Nazi power.

Resistance or complicity – or both?

The writer Sebastian Haffner, who fled Germany for England in 1938, described how Nazi stormtroopers confronted him in a Berlin library in March 1933.

When they asked him if he was an Aryan, Haffner answered, “Yes.” In retrospect, he believed his reply indirectly validated their question and thus facilitated Nazi efforts to eject Jews from the library.

Even if Haffner’s complicity was unintentional, his failure to speak out publicly on behalf of those whose humanity the Nazis denied helped that argument carry the day.

Nazi Germany was hardly a hotbed of resistance. Unlike Haffner, most Germans accommodated themselves to the Nazi regime and fought on its behalf until the bitter end of World War II.

Ordinary people may have pushed back against the regime in small ways, whether by telling political jokes or surreptitiously listening to foreign radio broadcasts. But they only rarely challenged the legal and political structures on which the regime’s genocidal violence depended.

It is hard to distill people’s actions down to their moral or political essence, because those actions take place within a social, economic and political context of which these individual actors are also an integral part.

Was the decision by a socialist politician in Berlin to purchase a shop owned by a Jewish acquaintance an act of humanity that helped that person escape Nazi tyranny or an act of complicity that facilitated Nazi efforts to “Aryanize” the German economy? The fact that it was probably both helps to explain why it proved politically contentious in Berlin’s city assembly after World War II.

Resistance as alibi

Following the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, German politicians could point to examples of German resistance to repudiate international assertions of German “collective guilt.” It took the combined forces of the Soviet Red Army and the Western Allies to bring down the Nazi regime. But the existence of a few heroic resisters gave credence to the idea of another Germany, one that could safely play a role in postwar socioeconomic and political reconstruction.

Although the July 20, 1944 plot to assassinate Hitler has become the iconic example of heroic German resistance against the Nazi regime, it was not always a comfortable reference point. Well into the 1950s, many citizens of the new West German democracy still found these officers’ wartime repudiation of their oath to Hitler to have been an act of treason.

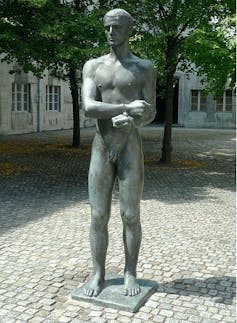

Now, the German Resistance Memorial Center is housed in the former offices of the Army High Command. In the building’s courtyard, a memorial statue and plaque mark the spot where Claus von Stauffenberg, the officer who placed the bomb that failed to kill Hitler, was summarily executed.

Yet this resistance story is complicated, too. Many of the plotters were German nationalists, skeptical of democracy and initially enthusiastic about Germany’s military successes.

Musical echoes

While in Berlin in the mid-1990s, I attended one of the annual commemorations of the failed 1944 assassination attempt. When a German military band played the German national anthem in the courtyard where von Stauffenberg was shot, I couldn’t help but hear the text of the original (and now banned) first stanza: “Deutschland, Deutschland über alles,” a 19th-century fantasy of national expansion that subsequently provided a soundtrack for Nazi imperial visions.

In my mind’s ear, “Germany, Germany over everything” overwhelmed the replacement text celebrating unity, justice and freedom.

And that’s really the point. The modern German army, the Bundeswehr, may now celebrate the July 20 plotters who turned on Hitler. But that celebration nonetheless sounds the strains of military complicity that made that sort of resistance necessary in the first place.

Ultimately, the Nazi regime depended on Germans’ willingness to deny the humanity of those it deemed outside the German “national community.”

To the extent that people inside and outside of Germany openly acknowledged and defended that humanity – often at fatal cost to themselves – they resisted the Nazi state’s fundamental aims.

Those resisters nonetheless failed to bring down Hitler or halt his genocidal project. So those who long for a heroic resistance should remain cautious about the possibility that such a project will produce short term political transformation. But they did save individual lives, and the ongoing effort to master the German past has provided vital means to interrogate the present.

From my perspective as a historian, I believe a contemporary call to resist the long-running practices of dehumanization in American politics and society should strive to hold the Trump administration and its enablers accountable.

But, as the example of Nazi Germany suggests, it is also important to recognize that resistance is not about declaring victory following a return to political normalcy. Germany’s effort to wrestle with the sources and aftermath of the Nazi regime, including Germans’ role in abetting or resisting its crimes has lasted more than 70 years.

In the United States, too, resistance can define itself as an ongoing project, not something that comes to an end with the Trump presidency.

Before the hashtag #Resist, the campaigns for “Black Lives Matter” and “Me Too” bore public witness to what those movements recognized as the systematic inhumanity in American society. That’s a historical legacy that goes far beyond the Trump administration.

If would-be resisters confront the historical sources and contemporary legacies of American inequality and exploitation, they can create an enduring legacy.

Paul Steege does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Will AI accelerate or undermine the way humans have always innovated?

An anthropologist’s new book lays out the formula for human innovation, from stone tools to supercomputers.…

Minneapolis united when federal immigration operations surged – reflecting a long tradition of mutua

Minnesotans from all walks of life, including suburban moms, veterans and protest novices, have bucked …

From moral authority to risk management: How university presidents stopped speaking their minds

Nearly 150 universities and colleges have adopted institutional neutrality pledges since 2023.