A socialist's primary win doesn't herald a workers revolution in the US

The victory of a Democratic Socialist in a New York primary will not lead to the dictatorship of the proletariat. It's an incremental addition to the long history of moderate socialism in the US.

Anyone anticipating a golden dawn of Marxist-Leninist communism soon in the United States might have to wait a while longer – perhaps forever.

The surprise victory of socialist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez over longtime Democratic New York Congressman John Crowley in a New York congressional primary has been featured prominently in the news. That was soon followed by headlines proclaiming the radical wing of the Democratic Party wants to take it over.

Both are noteworthy for a number of reasons. But they do not herald a workers’ revolution in the United States.

Despite the surprise around Ocasio-Cortez’s victory, the Democratic Socialists of America, or DSA, of which Ocasio-Cortez is a member, is not an upstart on the American political scene. Part of a long history of socialism in America, the Democratic Socialists have had relationships with progressive Democratic Party candidates and members of Congress for decades.

I have conducted research in areas of the world once dominated by socialism. When I teach my political ideologies class, I point to the long history of socialism that has contained many and various voices.

Socialism, in the broadest sense, posits that since society’s wealth is created by its workers, its workers should benefit from the fruits of their labors and administer them as they please.

The DSA’s history of moderation and collaboration with the American establishment sets it apart in history against more radical and utopian socialist parties, both in the U.S. and the rest of the world.

Socialism’s European history

Socialism, conservatism and liberalism constitute the three cardinal political ideologies.

Socialist ideas grew in importance as thinkers criticized the liberalism that has dominated the West since the Enlightenment in the 18th century.

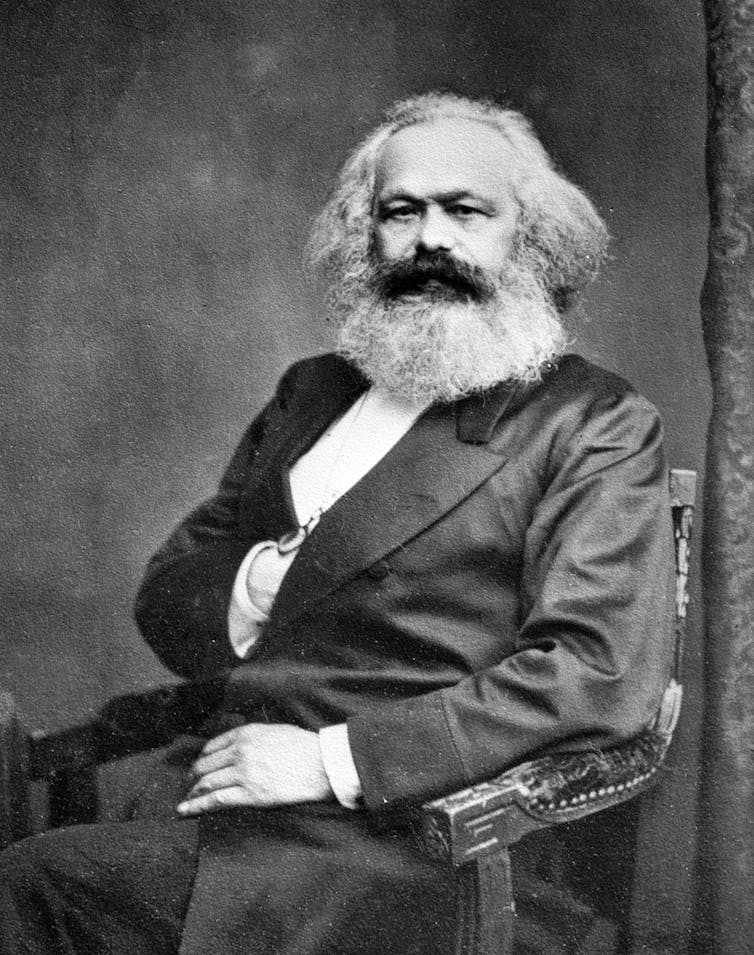

Socialism is often associated with Karl Marx. For Marx, capitalism unjustly concentrated the wealth of the many in the hands of a few.

Marx and his intellectual collaborator, Friedrich Engels, saw the misery of factory workers in 19th-century England. They expected the lives of the working class to get ever worse. At some point, they believed, workers would recognize their misery and overthrow the governments in advanced capitalist countries.

Then, Marx and Engels believed, a dictatorship would rule temporarily while society was reorganized in the interests of the workers. Eventually, this workers’ state would wither away to leave self-governing, satisfied workers with plenty of leisure time to engage in fulfilling pursuits. Marx named this latter state “communism.”

But socialism is not just about Marx.

English martyr St. Thomas More is sometimes seen as the earliest socialist. Socialism’s defining principle of equitable distribution of society’s goods appears in his 1516 work “Utopia.”

One of More’s characters states, “As long as there is any property … I cannot think that a nation can be governed either justly or happily: not justly, because the best things will fall to the share of the worst men; nor happily, because all things will be divided among a few … the rest being left to be absolutely miserable.”

The misery and poverty of those without adequate resources is a central theme in socialist thought.

Robert Owen, an early 19th-century British industrialist, wrote, “The rapid accumulation of wealth created by the industry of the people … [is] in the hands of capitalists who created none of it, and who misused all they acquired.”

Socialism comes to the United States

While socialist ideology was developed in England, with the notable contribution of certain Germans, like Marx and Engels, it wasn’t long before the idea gained a following in the United States. Robert Owen himself brought socialist ideas to the U.S. in his experimental, utopian community of New Harmony, Indiana.

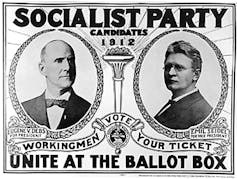

Eugene V. Debs is the political figure most associated with American socialism.

A railroad worker, Debs ran as the presidential candidate for the Socialist Party of America five times from 1900 to 1920. Debs remains American socialism’s most successful candidate, receiving 6 percent of the popular vote in 1912.

Debs held that workers in the United States were denied a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work. From the wealth that they create, said Debs, workers receive only about 17 percent.

Aligning himself with American workers links Debs, through Owen and More, to the fundamental tenet of socialism: a distribution of wealth that recognizes working people as the rightful owners of their product.

Democratic Socialists of America

The Socialist Party of America, came, as socialist parties often do, to a crisis in 1972.

The Debs faction wanted to perpetuate his pacifist position and opposed the Vietnam War. The other faction, led by political activist and author Michael Harrington, supported the war as a means to check the Soviet Union, whose human rights abuses and repressive authoritarian government were seen by some socialists as a betrayal of their movement.

Harrington also saw this as a way to distance himself from the anti-Americanism many associated with socialism. By 1973, Harrington had taken his faction out of the Socialist Party of America and formed the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee.

From the beginning, the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC) committed to working with the Democratic Party, labor, racial minorities and feminists.

Harrington adopted a pragmatic brand of socialism that he described as being “on the left of the possible.” It opposed Soviet-like concepts American socialists had once endorsed, such as centralization of the economy and public ownership of major enterprises.

The DSA was founded in 1982 by the merger of Harrington’s DSOC with the smaller New American Movement, a socialist group that had grown out of the student groups of the 1960s.

Socialism moves towards the center

Some long-held DSA policies are hardly distinguishable from today’s mainstream politics.

On important matters of international affairs such as trade and terrorism, the DSA has historically and consistently remained in touch with general American attitudes. The DSA’s platform since 1982 has included a national health service and reining in the power of multinational corporations.

Members of Congress, mayors and state legislators have been a part of the Democratic Socialists of America from its founding and throughout. By 1990, the DSA had 19 of its members in an elected office. That included two U.S. representatives – both from California – four state representatives and five mayors. This marginal success in elected office continues today as the party has 35 elected officials in its ranks.

While America’s most famous democratic socialist is Bernie Sanders, the Vermont senator and 2016 presidential candidate has not identified himself as a DSA member.

Ocasio-Cortez, who won the New York primary against an established Democratic party figure, espoused campaign positions that were right off of the 1979 DSOC platform – and recent Democratic Party positions. Her message was “economic, social, and racial dignity.” She called for single-payer health care and attacked the influence of large corporations.

Given her win in a safe Democratic seat, it appears likely that Ocasio-Cortez will be the 36th member of the DSA currently holding elected office in the U.S., thus extending the long history of socialism in America.

Daniel Pout has received funding from the Fulbright Porgram

Read These Next

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…

Drug company ads are easy to blame for misleading patients and raising costs, but research shows the

Officials and policymakers say direct-to-consumer drug advertising encourages patients to seek treatments…

Tiny recording backpacks reveal bats’ surprising hunting strategy

By listening in on their nightly hunts, scientists discovered that small, fringe-lipped bats are unexpectedly…