Your voting habits may depend on when you registered to vote

Not all who register vote. Research shows factors like timing and major tragic events can influence who, in the end, makes it out to the polls.

When eligible citizens register to vote, it doesn’t necessarily mean that they will turn out.

Voting in the U.S. is a two-step process. Citizens in every state except North Dakota must first register before casting a ballot.

As we discuss in our recently published article in Electoral Studies, the timing of when a voter registers to vote affects whether they vote in the upcoming election. It also relates to whether they become a repeat voter, or what political scientists refer to as a “habitual voter.”

Our findings could have an impact on turnout this November and future elections.

Making registration easier

In Canada, Germany and many other countries, voter registration is automatic. Not so in the U.S.

But there have been efforts over the last 25 years to make voter registration easier in the U.S.

Since 1993, with the passage of the National Voter Registration Act, all U.S. citizens can register to vote when they apply for a driver’s license or services at other governmental agencies. Citizens in 37 states are also able to register to vote online, making the process even more convenient.

More recently, a dozen states have enacted legislation changing voter registration at DMV offices from “opt-in” to “opt-out.” When applying for or renewing their driver’s license, you are automatically registered to vote unless you choose not to. Initial research on this approach from Oregon suggests that people who are automatically registered, compared to those already registered, were much younger and geographically reside in areas with a racially diverse population, lower income and lower education levels.

Of course, eligible citizens fall through the gaps. That’s where voter registration groups come in, fanning across the country, pen and paper (or smartphones) in hand, to register new voters.

As a final measure to encourage voting, citizens in 15 states and the District of Columbia may register at the polls on Election Day. Most eligible citizens, however, reside in a state in which they must register at least 29 days before Election Day.

But registration doesn’t equal voting. Not everyone who successfully registers prior to Election Day actually goes to the polls, especially in midterm elections.

From registration to the ballot box

In our study, drawing on nearly a decade of voting data in Florida, we find that when voters register affects their voting behavior.

Individuals who register in the waning months prior to Florida’s 29-day registration cutoff are more likely to vote in the upcoming election than others who register throughout the previous election cycle.

However, these last-minute registrants are less likely to vote in future elections. The act of registering to vote, and even voting in the next election, does not translate into becoming a repeat, regular voter. We think this is because those who register close to the deadline may be mobilized to do so by campaign events tied to the upcoming election, but they may not become regular voters for the long haul.

Relatedly, we are looking at what effect tragic events that occur well before an election may have on getting people to register and then turn out to vote.

For example, current evidence is mixed as to whether more young people are registering after a school shooting in Parkland, Florida. Has the social movement really increased the number of registrations among young voters? Similarly, are the thousands of Puerto Ricans who were displaced by Hurricane Maria registering to vote in Florida and other states?

It remains to be seen whether these individuals who have registered will vote in the 2018 midterms, and whether they will become habitual voters. Our research suggests that it’s not a sure bet.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

50 years ago, the Supreme Court broke campaign finance regulation

A gobsmacking amount of money is spent on federal elections in the US. The credit or blame for that…

When civil rights protesters are killed, some deaths – generally those of white people – resonate mo

From the civil rights era of the 1960s until today, white victims of government violence have received…

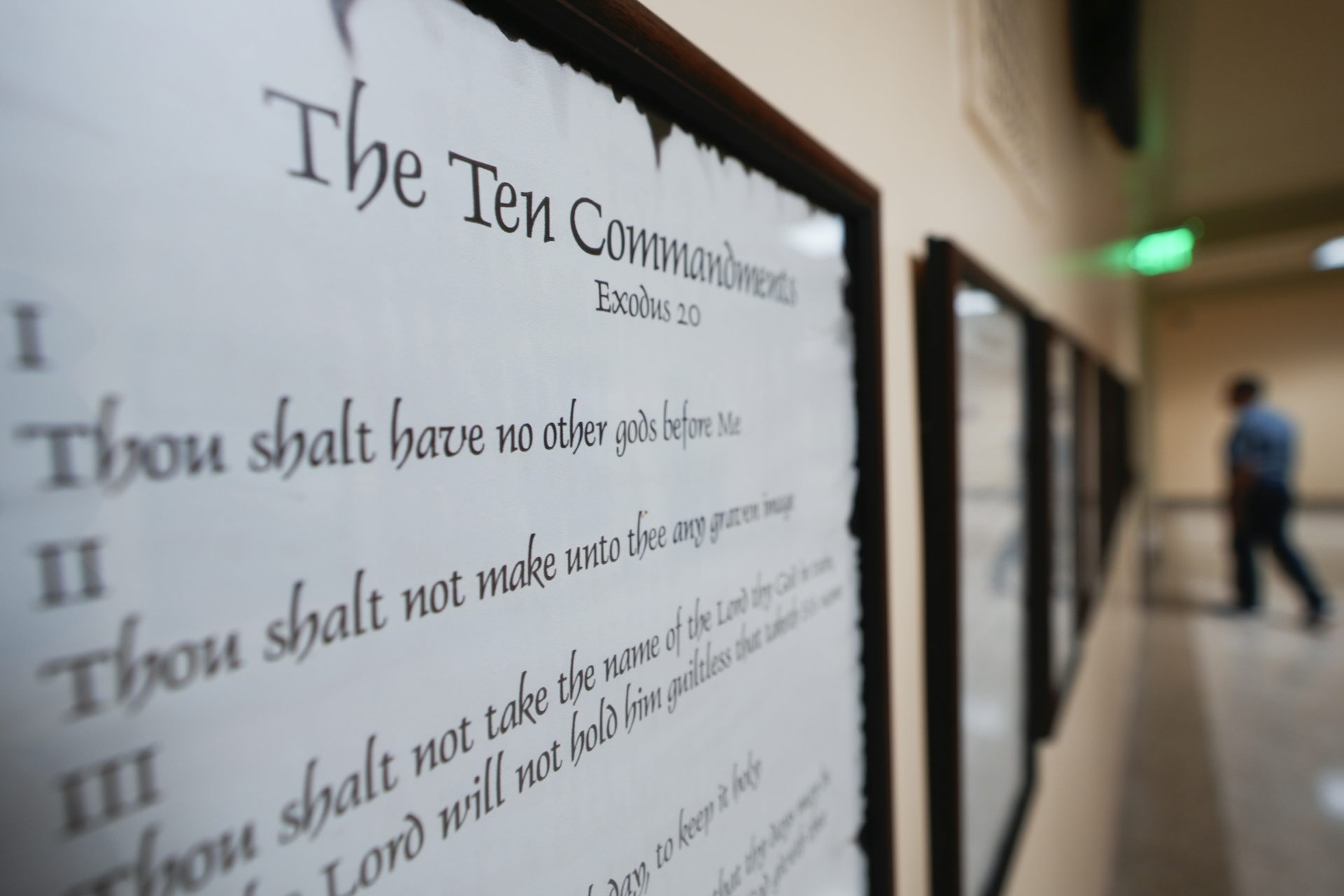

Baptists have helped shape debate about religious freedom for over 400 years – up to today’s 10 Comm

The phrase ‘separation of church and state’ dates back to a letter from Thomas Jefferson to a Baptist…