California's jungle primary sets up polarized governor's race for November

The top two system in California was created to draw out more centrist candidates and voters, but data from primaries past show it's just not working.

Voters who took part in California’s innovative and anti-party “jungle” primary delivered a typical and predictably partisan result in the governor’s race.

They sent Democratic Lt. Governor Gavin Newsom as the heavy favorite into a November contest against Republican businessman John Cox. With the liberal Newsom positioning himself as a Bay Area Bernie Sanders, and staunchly conservative Cox touting his Twitter endorsement from President Donald Trump, the battle at the top of the ticket will be fought from the ideological poles. Incumbent Dianne Feinstein is safe in the Senate, but key House districts are too close to call as of this writing.

This was not how California’s top two system, or “jungle” primary, was supposed to work.

The hope of reformers who backed it as a ballot proposition nearly a decade ago was that the new rules – which let every voter cast a ballot for any candidate in the primary, with the top two advancing to the general election – would act as an antidote to partisan polarization.

Parties hated the idea. It meant no party was guaranteed a spot in the top two. Voters backed it, ready to experiment with anything in a rapidly polarizing state.

After four primaries run under the new system, the hopes of reformers have yet to materialize. And some of the fears of its opponents have roiled congressional races run under the top two rules, as parties struggle to avoid being shut out of the November ballot in competitive districts.

Here’s how the top two primary is supposed to shake up California politics.

Hope for a centrist electorate

First, it gives voters who don’t affiliate with a political party – a bloc that is now slightly larger than the Republican Party in the state that once produced Nixon and Reagan – a bigger voice in primaries. Voters with “no party preference” now make up 25.5 percent of registered voters, trailing Democrats at 44.6 percent but ahead of Republicans at 25.1 percent.

Before the reform, independents could vote in a party primary only if the party allowed it. Democrats did, Republicans didn’t, and very few independents turned out in primaries.

The idea was that by opening up primaries to all voters, regardless of party, a flood of new centrist voters would arrive. That would give moderate candidates a route to victory without having to bend toward the ideological extremes to appeal to party loyalists, as often happens in primaries.

Yet when the top two went into effect, no flood of independents turned out to the polls. The trickle continued.

As my colleague Seth Hill and I showed in a comparison of participation in the 2008 and 2010 elections, before the top two primary system took effect, turnout by voters with no party preference actually declined from 17.7 percent to 17.2 percent of registered voters. Those who did vote had the option of casting a ballot for any candidate, regardless of party, an important expressive right brought by the new rules. But the reform failed to deliver a new pool of moderate, nonpartisan voters to buttress centrist or independent candidates.

Hope for more centrist candidates

At least so far, candidates running from the center have also not fared particularly well under the new rules. My other research with Justin Phillips and Boris Shor looked at the positions that congressional and state legislative candidates took on a range of issues in the first races held under top two rules in 2012. We compared them with the positions of the average voter in each district.

If the top two approach had fulfilled its goals, we expected to see a closer match between candidates and voters in 2012, compared with contests held under the old rules in 2010.

However, we found no such evidence. Candidates did not represent voters any better after the reforms, taking positions just as polarized as they did before the top two. We detected no shift toward the ideological middle.

In our findings, we did note one unintended flaw in the top two rules that year, a flaw that has turned some congressional races into a jungle this year. In a battleground district, a party with strong voter support can get shut out of the November election. If one party fields two strong candidates and the other has three or four of them splitting the vote, the party with fewer candidates in the primary can monopolize space on the general election ballot.

This is exactly what happened in California’s 31st Congressional District, where Democrats held a five-point lead in party registration. Two Republicans advanced when four Democrats split the vote in 2012, leaving November voters powerless to pick which party would represent them in a swing district.

That situation, which is without question bad for democratic representation, is threatening to occur again this year. Right now, in three toss-up congressional districts, Democrats are struggling to win a place on the November ballot because they have many well-funded candidates dividing up the party base. All three primaries are too close to call as of publication.

Strategy trumped ideas

Regardless of the outcome, the quirks of the top two system have driven the dynamics of all three close congressional races. Instead of debating the merits of candidates, voters have been debating which one has the best chance of making it to November.

Democrats looking to consolidate around a front-runner in one of these races eagerly awaited any polling numbers to guide them, then became bitterly divided over two conflicting polls released just before the election.

Meanwhile, political consultants have taken up the invitation to mischief created by the new rules.

For example, national Democratic groups wanted to splinter the Republican vote, so they spent money attacking a strong Republican candidate in one San Diego district, while also attempting to prop up weaker Republicans in two Orange County districts. Welcome to the jungle primary, where races can become more about strategic fights and less about battles of ideas.

This year’s governor’s race was supposed to be the one that finally fulfilled the promise of the top two system. In early polling, former Speaker of the Assembly and Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa ran far ahead of political newcomer John Cox. Villaraigosa positioned himself as a moderate Democrat, backing charter schools and refusing to embrace a state single-payer health plan. If he made the top two, he hoped to cobble together a coalition of moderate Democrats, independents and perhaps even a few Republicans to defeat the more liberal Newsom.

That campaign might have changed California politics. Yet Villaraigosa’s dream, like many of the dreams of top two reformers, did not come true. He lost, and now voters face a choice between two partisan and more polarizing party candidates.

Thad Kousser and Seth Hill received funding from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation

Read These Next

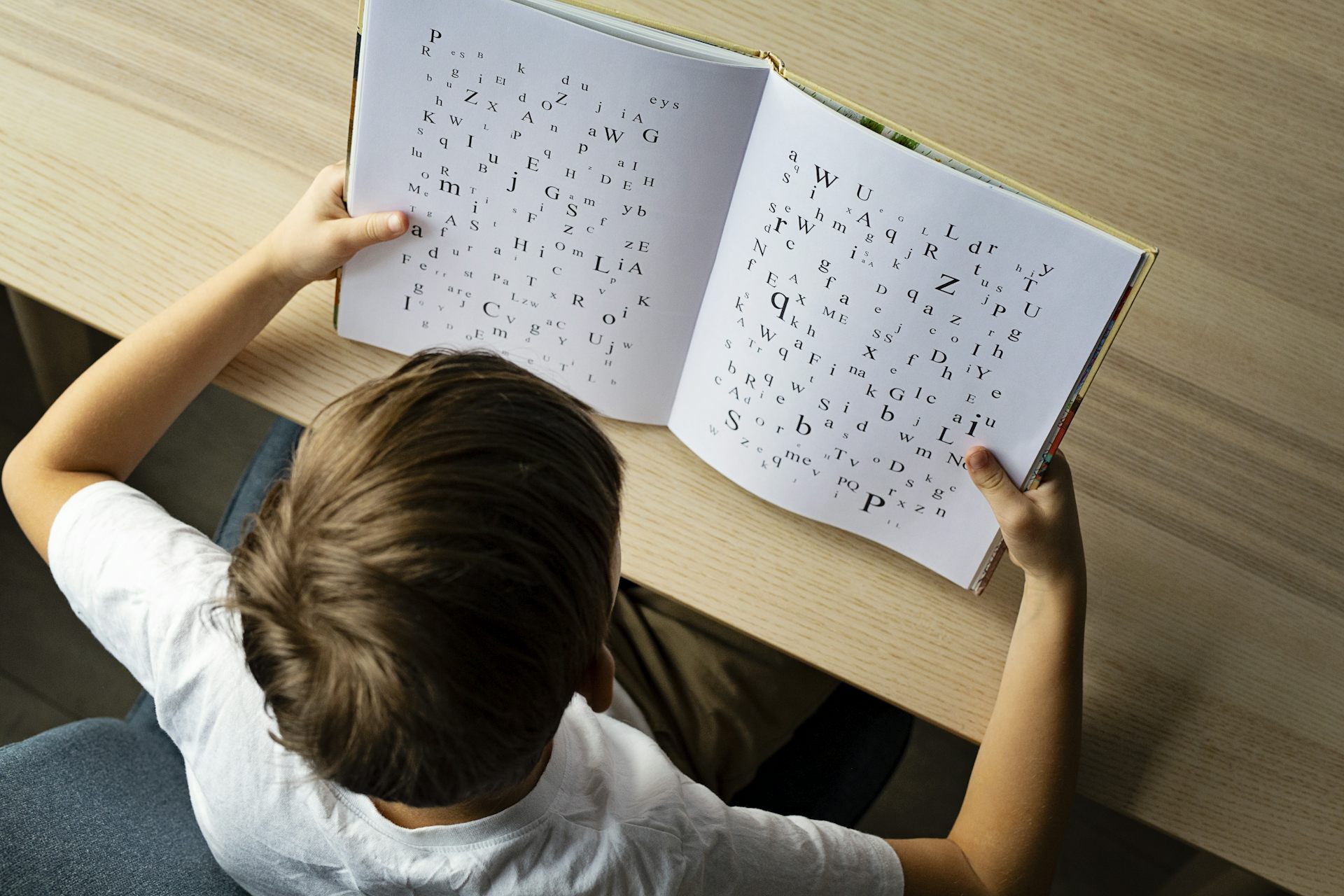

Nearly every state in the US has dyslexia laws – but our research shows limited change for strugglin

Dyslexia laws are now nearly universal across the US. But the data shows that passing a law is not the…

Citizenship voting requirement in SAVE America Act has no basis in the Constitution – and ignores pr

The House has passed a bill to require proof of citizenship for voting. Although it likely won’t become…

How the 9/11 terrorist attacks shaped ICE’s immigration strategy

The growth of today’s aggressive immigration tactics traces back 25 years, when enforcement took on…