Unearthed mummy recalls an Iran before the ayatollahs

A mummy unearthed during construction in Iran may be the body of a former shah. For the Islamic regime, the discovery is an unwelcome reminder of Iran's secular past. For protesters, it holds promise.

As a historian, I well know that the past has a habit of coming back. And, sometimes, it wreaks havoc on the present.

That’s the situation now confronting Iran after a mummy was discovered during construction on a building in Tehran.

Everything old is new again

Iran’s 1979 Revolution brought into power a conservative Islamic regime.

When that happened, some Western scholars – myself included – feared that the new ayatollahs would visit destruction on anything non- or pre-Islamic. I was part of a group of academics who created a new association of Iranologists in Europe to ensure continued study of Iran’s past.

To our relief, the new government admirably continued scholarly research on the past, both Islamic and pre-Islamic, maintaining archaeological excavations and publishing the results.

But the revolutionary Islamic government did seek to erase one inconvenient part of Iran’s past. After the last Iranian monarch, or shah, fled the country in early 1979, a group of Revolutionary Guards demolished the mausoleum of his father, Reza Shah.

Reza Shah, the founder of Iran’s Pahlavi dynasty, died in exile in South Africa in 1944, after being deposed by the British during World War II. His body was brought to Cairo, where it was mummified in order to preserve it.

It remained there until his son, Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi – who had succeeded him on the Iranian throne – brought it to Tehran and interred it in a specially built mausoleum.

When the mausoleum was destroyed in 1979 during Iran’s revolution, Reza Shah’s mummy disappeared in the rubble. Nothing was known of its fate.

Unearthing the shah’s dynasty

Now, construction at a shrine on the site of what used to be the mausoleum has turned up a mummified body. Since mummification is extremely rare in Islam, most observers believe that it is the late shah.

I agree. Judging by the pictures I’ve seen online, the dead man was a person of some significance, with a military bearing. The mummy’s well-preserved face even bears a certain eerie resemblance to Reza Shah’s son, the Shah Muhammad.

This mummy is attracting global attention – and not just for its archaeological interest. It is also politically charged.

Politics in Iran today are fluid and volatile. The ruling Islamic regime is split, as is often the case, between leaders who seek more positive engagement with the West and those who maintain an anti-American foreign posture.

As President Donald Trump contemplates scrapping the Iran nuclear deal, Iranians are now hotly debating how the country should react if the agreement is indeed undone. These discussions exacerbate existing divisions within the government.

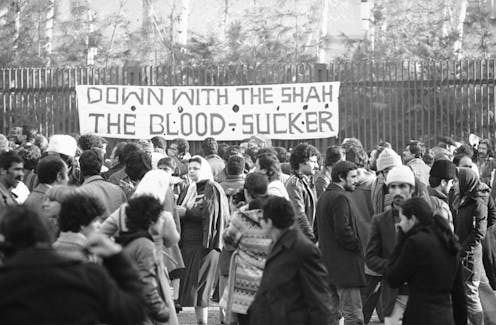

Meanwhile Iran’s economy is weak and its currency in free fall. Nationwide protests erupted in cities across the country in early 2018, with crowds shouting anti-regime slogans – some of them praising the last shah or expressing nostalgia for his reign.

For some demonstrators in Iran and in exile, the mummy of a once-powerful shah appears to hold promise. It is a symbol of a different era – a reminder that Iran hasn’t always been an Islamic Republic.

A crown prince in exile

For those in power, however, the return of a dead shah represents a threat.

The ayatollahs are not, I think, worried about a return of the Pahlavi dynasty. They know very well that most supporters of Iran’s former monarchy are in comfortable exile in Los Angeles and Europe.

And though opposition to Iran’s current regime has spiked in recent months, domestic support for a return of the Pahlavis is negligible.

But the shah’s mummy still has galvanizing power among those opposed to Iran’s hard-line current regime because it symbolizes a government not built on religion.

The Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi, son of Iran’s last shah, lives in exile in the United States. He has called on the government in Tehran to treat his grandfather’s body respectfully, in accordance with the requirements of the Quran.

But, in this context, demanding respect for the dead is also a political calculation. Calling the Iranian people “the true guardians of Reza Shah’s legacy” on Twitter, the crown prince has asked citizens to support his family.

By this, it’s fairly clear he means not only his mummified grandfather but also his own claim to the throne. In interviews from Los Angeles, the exiled crown prince is increasingly open about wanting to see Iran’s monarchy restored.

Meanwhile the government has taken the mummy into custody while DNA tests are done to confirm its identity. But, conveniently for the regime, that process could take weeks or months – long enough for the protesting crowds to lose interest.

As a catalyst for those hostile to Iran’s Islamic regime, the dead shah’s body may work for a while. But if Iran’s fragmented opposition is to get rid of the powerful ayatollahs, they’ll need more than a mummy.

David J. Wasserstein does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…

Will AI accelerate or undermine the way humans have always innovated?

An anthropologist’s new book lays out the formula for human innovation, from stone tools to supercomputers.…

When civil rights protesters are killed, some deaths – generally those of white people – resonate mo

From the civil rights era of the 1960s until today, white victims of government violence have received…