Why top US universities have law schools but not police schools

The demise of the first academic department dedicated to policing at the University of California has left unanswered questions about the best way to educate cops.

In response to protests calling for police reform and accountability, some U.S. police departments are partnering with colleges and universities to develop anti-bias training for their employees.

In Washington D.C., for example, officers will take a critical race theory class at the University of the District of Columbia Community College. The idea of providing liberal arts education to officers to improve police-community relations and productivity is not new.

As early as 1967, a federal commission charged with finding solutions to rising crime and police brutality recommended that all police “personnel with general enforcement powers have a baccalaureate degree.”

However, recent research indicates that education has mixed results. While some evidence suggests that college-educated officers are less likely to use force, it also shows they are less satisfied with their jobs than peers with less education.

As a postdoctoral fellow, I have been studying police reform movements of the 1950s and ‘60s. I was surprised to learn of the long and complicated relationship between the police and academia.

The story of the School of Criminology at the University of California, Berkeley, in particular, reveals the challenges of developing a true “police science” – a way of improving practices within this profession by involving police in university-level research and teaching. The potential benefits of such a science are unclear, as police work has struggled to find a home in academia.

The following story is constructed from archival records at Berkeley’s Bancroft Library.

College cops at Berkeley

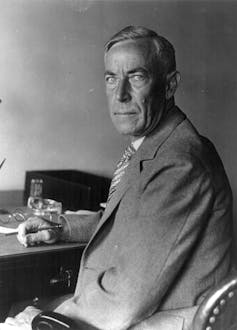

August Vollmer has been described by some scholars as the most influential police reformer in modern history. Vollmer served as the chief of the Berkeley police from 1909 to 1932, where he and his protégés improved the lie detector test, developed the world’s first fingerprinting system, adopted radio communication and automobile patrol, and set up the first crime lab in the country.

Of all Vollmer’s projects, the one dearest to his heart was the professional development of police through education. To this end, he established the world’s first police academy at Berkeley in 1908. Defying convention, he also regularly hired college students to work on his force. At the time, academic training was often considered a handicap to good police work because it made officers bookish.

Vollmer’s interest in academia was clear: He wanted to develop a team of expert police who would be sensitive to the needs of the communities they served. In 1930, he wrote: “Why should not the cream of the nation be perfectly willing to devote their lives to the cause of service providing that service is dignified, socialized and professionalized?”

Vollmer and his colleagues partnered with Berkeley in pursuit of this vision. In 1916, they began offering summer university courses for police officers. By 1923, they were conferring criminology degrees through the political science department. In 1950, they founded the School of Criminology – the first standalone department at Berkeley dedicated to police science. The school required future officers to take courses in traditional academic departments – sociology, history, mathematics – alongside practical training in police work – things like fingerprinting and interrogation. They could receive a Bachelor of Arts, a Bachelor of Science or Master of Criminology upon completion.

The school was run by police for police. O.W. Wilson, the first dean of the school, was a police officer who did not have a Ph.D. At the time, it was rare, although not unprecedented, for working professionals to lead academic departments at Berkeley.

Students came from all over the world to study at the School of Criminology. In the Bancroft archives, I found letters from alumni as far away as the Chinese Ministry of the Interior. Vollmer’s work inspired similar programs in other states including Indiana, Washington and Michigan. It also made the case for offering police courses at the other public higher education systems in the state: the California State University and California Community Colleges.

'Too occupational’

Clark Kerr, former president of the University of California, had major reservations about educating police at Berkeley.

Kerr was one of the architects of the Master Plan for Higher Education in California, which in 1960 laid out a system of higher education in the state as it still exists today. That plan called for coordination between different types of public institutions. Occupational training programs – like those for police – would be housed at Cal State campuses and community colleges. The University of California campuses would be responsible for scholarship and providing the state’s top performing students with a liberal arts education.

In line with this perspective, a faculty committee reviewed the School of Criminology in 1957, and found it to be “not a proper pursuit for an undergraduate” at Berkeley.

They wrote: “Its aims are too ill-defined to constitute a truly intellectual discipline, its techniques too disparate and fragmentary, and its perspective too occupational.”

The committee recommended completely dismantling the School of Criminology. However, by then, the school had become far too important to California law enforcement to go down without a fight.

The Bancroft’s archives contain dozens of letters from police officers and other officials asking Berkeley administrators to stall the school’s closure. They include petitions from faculty in police training programs at Cal State campuses. Without Berkeley supplying the Cal State programs with police professors and research on policing, they feared their programs would suffer.

As a condition of staying at Berkeley, the school had to look more like a traditional academic department. It would have to hire Ph.D.‘s from the social sciences, eliminate vocational coursework and focus on graduate education. Several former officers who were on faculty left the department for more hospitable workplaces. Dean Wilson went on to become the chief of police in Chicago and was replaced by Joseph Lohman, a sociologist from the University of Chicago who also worked as Cook County Sheriff.

After 1960, the school became a place for sociologists to study crime. Many criminology faculty were outspoken critics of the police. In 1971, criminology professor Tony Platt was arrested by the Berkeley police during a political protest. The relationship between the school and the local law enforcement it once trained was deteriorating.

In 1972, the school came under fire again.

A review committee rebuked it for its “current pursuit of academic goals in large part divorced from a professional orientation.” In other words, it had succeeded too well in distancing itself from its original mission of educating police officers.

This time around, few law enforcement officials came to its defense. Despite protests from student groups, Berkeley’s School of Criminology closed its doors for good in 1976.

Lessons from Berkeley

Berkeley’s School of Criminology was one of the most ambitious projects in police education ever undertaken in the U.S. After its demise, police professors came under attack at other universities and in professional associations for a “lack of academic prestige or acceptance.” Under constant threat of closure, starvation or neglect, schools of police science reinvented themselves as criminal justice departments. This required expanding their focus to include the courts and corrections.

As other scholars have pointed out, criminal justice is a poor replacement for police science. Students who major in criminal justice do not necessarily plan to become police officers. Nor do faculty need any knowledge of or experience with the police. A recent survey of 2,109 officers in eight metropolitan police departments found that 45 percent of officers had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Only half of these majored in criminal justice.

Even if these programs were designed exclusively for police, their absence at major research universities is telling. The vast majority of campuses of the University of California do not offer degrees in criminal justice.

In 2016, California State University, Sacramento launched the Law Enforcement Candidate Scholars Program, which prepares college students from all majors to become police officers through workshops on policing and internships in law enforcement agencies. It may provide valuable information on creating and sustaining police-university partnerships.

For now, as policymakers, educators and police departments consider various strategies for police reform – including the ever-popular suggestion that officers be required to have a college degree – it is important to remember the challenges of integrating this profession into the Ivory Tower. It is unclear whether college-level education is beneficial to police, what kind is most useful, how it should be delivered or by whom.

Precisely because major research universities have been reluctant to adopt a robust science of the police, we don’t have much evidence for what works and what doesn’t. It may be time for educators to ask themselves: What harm is our reluctance to study and educate this profession causing our society?

Nidia Bañuelos does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…

Drug company ads are easy to blame for misleading patients and raising costs, but research shows the

Officials and policymakers say direct-to-consumer drug advertising encourages patients to seek treatments…

Bad Bunny says reggaeton is Puerto Rican, but it was born in Panama

Emerging from a swirl of sonic influences, reggaeton began as Panamanian protest music long before Puerto…