March for Our Lives awakens the spirit of student and media activism of the 1960s

Young activists are using journalism to advance their cause. Though their work echoes student activists and journalists of the 1960s, they use new tools not available to the activists of that era.

A student movement against gun violence is receiving sustained news coverage.

Students are using social and news media to build momentum and advocate for legislation in the wake of a Feb. 14 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. A former student opened fire in the school, killing 17 people.

As an expert on the history of youth journalism and media activism that blossomed in the 1960s, I see today’s students as part of a continuum that began with that movement.

Despite not all being old enough to vote, Parkland students are putting pressure on government and private corporations to meet their demands.

Florida Gov. Rick Scott signed a gun safety bill into law on March 9, while companies like Delta Airlines and Hertz have cut ties with the National Rifle Association. The student movement is a force to be reckoned with.

Students create their own media

Student journalists used media as a key tool for activism in the widespread social movements of the 1960s, journalism scholar Kaylene Dial Armstrong writes in her book “How Journalists Report Campus Unrest.” One notable student protest happened in Washington, D.C., 50 years ago.

In the spring of 1968, student demonstrators occupied the administration building at Howard University, a historically black school in Washington to protest racial inequality. Starting on March 19, more than 1,000 students shut down administrative operations at the university until March 23.

One of the lead organizers, Adrienne Manns, was the editor-in-chief of Howard’s student newspaper, The Hilltop. The Hilltop supported the protesters from the outset.

“It is the responsibility of The Hilltop to present issues and suggest solutions,” read a front-page editorial on March 8, 1968, in the lead-up to the occupation.

The organizers saw the protest as part of the broader civil rights movement of the 1960s. Armstrong writes that Howard students demanded that the administration make the curriculum more relevant to black students and give them authority over the student paper. The administration met these demands on March 23, and the students ended their occupation.

In 1968, Howard’s student journalists presented these issues and solutions, covering events supporting black pride and identity. They also suggested university-wide reforms. Suggestions included a black-centric curriculum, a work-study program allowing students to connect with the surrounding community and more student control over campus activities.

The Hilltop’s journalists provided deeper reporting that year on issues than the objective and detached approach the professional media gave student protests. Manns demonstrated that student journalists could draw on their experiences as activists, using media to tell alternative narratives, build public support and create change.

Later in 1968, as I explore in my own research, university students across Ontario, Canada, joined journalists who were on strike to advocate for union recognition. At the time, the Peterborough Examiner in Ontario was owned by multinational media corporation Thomson Newspapers – today known as Thomson Reuters. Hundreds involved in the student movement from at least six universities joined employees on the picket line. Together, they started a local off-campus newspaper, The Free Press, which they published for nearly two months.

The Free Press described itself as a local “alternative to the Examiner” and a “community-conscious newspaper like the Peterborough Examiner was before Thomson took over.”

Thomson Newspapers continued publishing the Examiner during the strike, but it carried little reporting on the strike and other local information. Some Free Press articles were focused on the strike, criticizing Thomson Newspapers and the profit-driven press. But most articles reported local news on a range of topics, including municipal politics and sports.

The Free Press helped fill a gap in local news coverage about the strike. The alternative paper also helped the Thomson journalists put pressure on Thomson to negotiate with them. While Thomson didn’t meet all of their demands, the journalists ended their strike on May 6, 1969, and returned to work.

Parkland students produce multimedia journalism

Today, students have more media tools at their disposal than in 1968. During the Parkland shooting, student David Hogg, 17, took out his phone and started filming and interviewing classmates. He was hiding in a school closet at the time, as the gunman walked the halls.

“If I was going to die, I wanted to die doing what I love, and that’s storytelling,” Hogg said.

People around the world also got an inside view of the school shooting from students who posted photos and video clips on Snapchat. Soon after the shooting began, Snapchat published a featured story titled “High School Shooting” on its new desktop feature called Snap Maps. The feature was released two days before the shooting and consisted of a group of snaps submitted by users in that location.

Students Nikhita Nookala and Christy Ma, both 17, published their account of the shooting in The Eagle Eye, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School’s newspaper. Unlike journalists at commercial news outlets, Nookala and Ma drew on their unique experiences as journalists and survivors to build trust with community members and legitimize their coverage.

The revolution will be tweeted

The Parkland students have used social media on a daily basis since the shooting.

Student organizer Emma González created a Twitter account on Feb. 18 — four days after the Parkland shooting. Now she has 1.2 million followers. She’s using Twitter to share messages of solidarity and to ridicule politicians about gun control.

“People always say, ‘Get off your phones,’ but social media is our weapon,” says student organizer Jaclyn Corin. “Without it, the movement wouldn’t have spread this fast.”

In the aftermath of the shooting, another student organizer Cameron Kasky used the hashtag #NeverAgain, which has gone viral as a rallying cry for the movement.

By using various media, the Parkland students have demonstrated they’re politically engaged, despite what some critics say about millennials being politically disinterested. In their book “Young People and the Future of News,” researchers Lynn Schofield Clark and Regina Marchi call these practices “connective journalism.” They explain how youth move from interest in an issue to political participation in a social media age.

History demonstrates that student-led media could provide a platform for youth to express their opinions, control their messages and facilitate political participation.

Seen in this light, it’s important to recognize how young people are using social and news media as a powerful mobilizing tool, like students involved in March for Our Lives are doing. For the Parkland teens, media provide a weapon to advocate for gun reform and mobilize young people to vote. Although students used media for activism in the 1960s, students now have more tools to quickly spread their messages widely and, in doing so, shape national conversations.

Errol Salamon does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

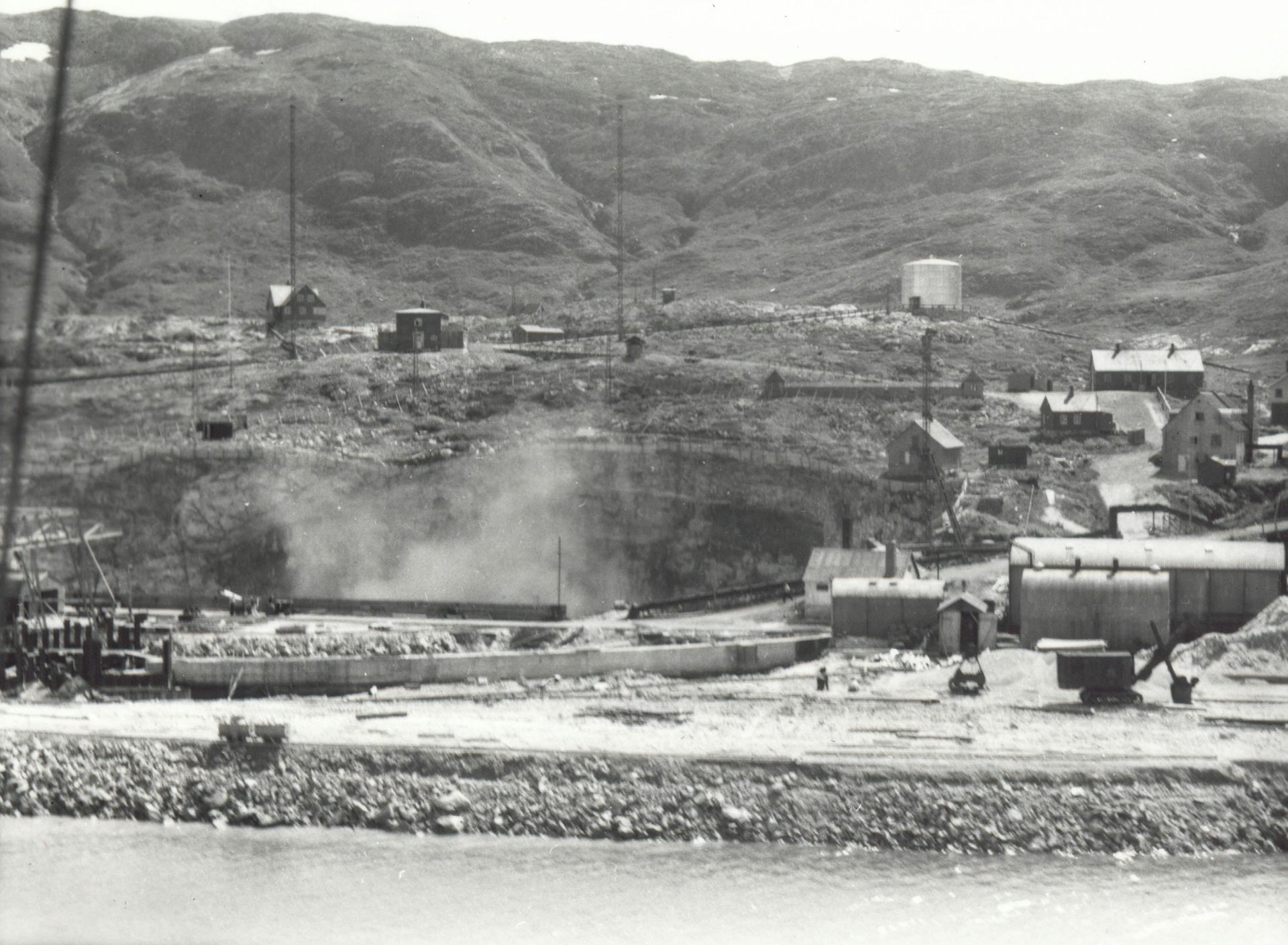

In World War II’s dog-eat-dog struggle for resources, a Greenland mine launched a new world order

Strategic resources have been central to the American-led global system for decades, as a historian…

Revisiting the story of Clementine Barnabet, a Black woman blamed for serial murders in the Jim Crow

In 1912, a young Black woman’s supposed religious beliefs were quickly blamed to make sense of a terrifying…

3 generations of Black Philadelphia students report persistent anti-Black attitudes in schools

A sociologist explains how Black students in Philadelphia navigate racial prejudice and find affirmation…