Black Americans mostly left behind by progress since Dr. King's death

Fifty years after MLK's death, a minority politics scholar assesses black progress in the US based on poverty, jobs and wealth. "In some ways," she concludes, "we've barely budged as a people."

On Apr. 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, while assisting striking sanitation workers.

That was almost 50 years ago. Back then, the wholesale racial integration required by the 1964 Civil Rights Act was just beginning to chip away at discrimination in education, jobs and public facilities. Black voters had only obtained legal protections two years earlier, and the 1968 Fair Housing Act was about to become law.

African-Americans were only beginning to move into neighborhoods, colleges and careers once reserved for whites only.

I’m too young to remember those days. But hearing my parents talk about the late 1960s, it sounds in some ways like another world. Numerous African-Americans now hold positions of power, from mayor to governor to corporate chief executive – and, yes, once upon a time, president. The U.S. is a very different place than it was 50 years ago.

Or it is? As a scholar of minority politics, I know that while some things have improved markedly for black Americans since 1968, today we are still fighting many of the same battles as Dr. King did in his day.

That was then

The 1960s were tumultuous years indeed. During the long, hot summers from 1965 to 1968, American cities saw approximately 150 race riots and other uprisings. The protests were a sign of profound citizen anger about a nation that was, according to the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, “moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.”

Economically, that was certainly true. In 1968, just 10 percent of whites lived below the poverty level, while nearly 34 percent of African-Americans did. Likewise, just 2.6 percent of white job seekers were unemployed, compared to 6.7 percent of black job seekers.

A year before his death, Dr. King and others began organizing a Poor People’s Campaign to “dramatize the plight of America’s poor of all races and make very clear that they are sick and tired of waiting for a better life.”

On May 28, 1968, one month after King’s assassination, the mass anti-poverty march took place. Individuals from across the nation erected a tent city on the National Mall, in Washington, calling it Resurrection City. The aim was to bring attention to the problems associated with poverty.

Ralph Abernathy, an African-American minister, led the way in his fallen friend’s place.

“We come with an appeal to open the doors of America to the almost 50 million Americans who have not been given a fair share of America’s wealth and opportunity,” Abernathy said, “and we will stay until we get it.”

This is now

So, how far have black people progressed since 1968? Have we gotten our fair share yet? Those questions have been on my mind a lot this month.

In some ways, we’ve barely budged as a people. Poverty is still too common in the U.S. In 1968, 25 million Americans — roughly 13 percent of the population — lived below poverty level. In 2016, 43.1 million – or more than 12.7 percent – do.

Today’s black poverty rate of 22 percent is almost three times that of whites. Compared to the 1968 rate of 32 percent, there’s not been a huge improvement.

Financial security, too, still differs dramatically by race. Black households earn $57.30 for every $100 in income earned by white families. And for every $100 in white family wealth, black families hold just $5.04.

Another troubling aspect about black social progress – or should I say the lack thereof – is how many black families are headed by single women. In the 1960s, unmarried women were the main breadwinners for 20 percent of households. In recent years, the percentage has risen as high as 72 percent.

This is important, but not because of some outmoded sexist ideal of the family. In the U.S., as across the Americas, there’s a powerful connection between poverty and female-headed households.

Black Americans today are also more dependent on government aid than they were in 1968. Currently, almost 40 percent of African-Americans are poor enough to qualify for welfare, housing assistance and other government programs that offer modest support to families living under the poverty line.

That’s higher than any other U.S. racial group. Just 21 percent of Latinos, 18 percent Asian-Americans and 17 percent of whites are on welfare.

Finding the bright spots

There are, of course, positive trends. Today, far more African-Americans graduate from college – 38 percent – than they did 50 years ago.

Our incomes are also way up. Black adults experienced a more significant income increase from 1980 to 2016 – from $28,667 to $39,490 – than any other U.S. demographic group. This, in part, is why there’s now a significant black middle class.

Legally, African-Americans may live in any community they want – and from Beverly Hills to the Upper East Side, they can and do.

But why aren’t those gains deeper and more widespread?

Some prominent thinkers – including the award-winning writer Ta-Nehisi Coates and “The New Jim Crow” author Michelle Alexander – put the onus on institutional racism. Coates argues, among other things, that racism has so held back African-Americans throughout history that we deserve reparations, resurfacing a claim with a long history in black activism.

Alexander, for her part, has famously said that racial profiling and the mass incarceration of African-Americans are just modern-day forms of the legal, institutionalized racism that once ruled across the American South.

More conservative thinkers may hold black people solely accountable for their problems. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Ben Carson is in this “personal responsibility” camp, along with public intellectuals like Thomas Sowell and Larry Elder.

Depending on who you ask, then, black people aren’t much better off than in 1968 because either there’s not enough government help or there’s way too much.

What would MLK do?

I don’t have to wonder what Dr. King would recommend. He believed in institutional racism.

In 1968, King and the Southern Christian Leadership Council sought to tackle inequality with the Economic Bill of Rights. This was not a legislative proposal, per se, but a moral vision of a just America where all citizens had educational opportunities, a home, “access to land,” “a meaningful job at a living wage” and “a secure and adequate income.”

To achieve that, King wrote, the U.S. government should create an initiative to “abolish unemployment,” by developing incentives to increase the number of jobs for black Americans. He also recommended “another program to supplement the income of those whose earnings are below the poverty level.”

Those ideas were revolutionary in 1968. Today, they seem prescient. King’s notion that all citizens need a living wage portends the universal basic income concept now gaining traction worldwide.

King’s rhetoric and ideology are also obvious influences on Sen. Bernie Sanders, who in the 2016 presidential primaries advocated equality for all people, economic incentives for working families, improved schools, greater access to higher education and for anti-poverty initiatives.

Progress has been made. Just not as much as many of us would like. To put it in Dr. King’s words, “Lord, we ain’t what we oughta be. We ain’t what we want to be. We ain’t what we gonna be. But, thank God, we ain’t what we was.”

Sharon Austin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…

Drug company ads are easy to blame for misleading patients and raising costs, but research shows the

Officials and policymakers say direct-to-consumer drug advertising encourages patients to seek treatments…

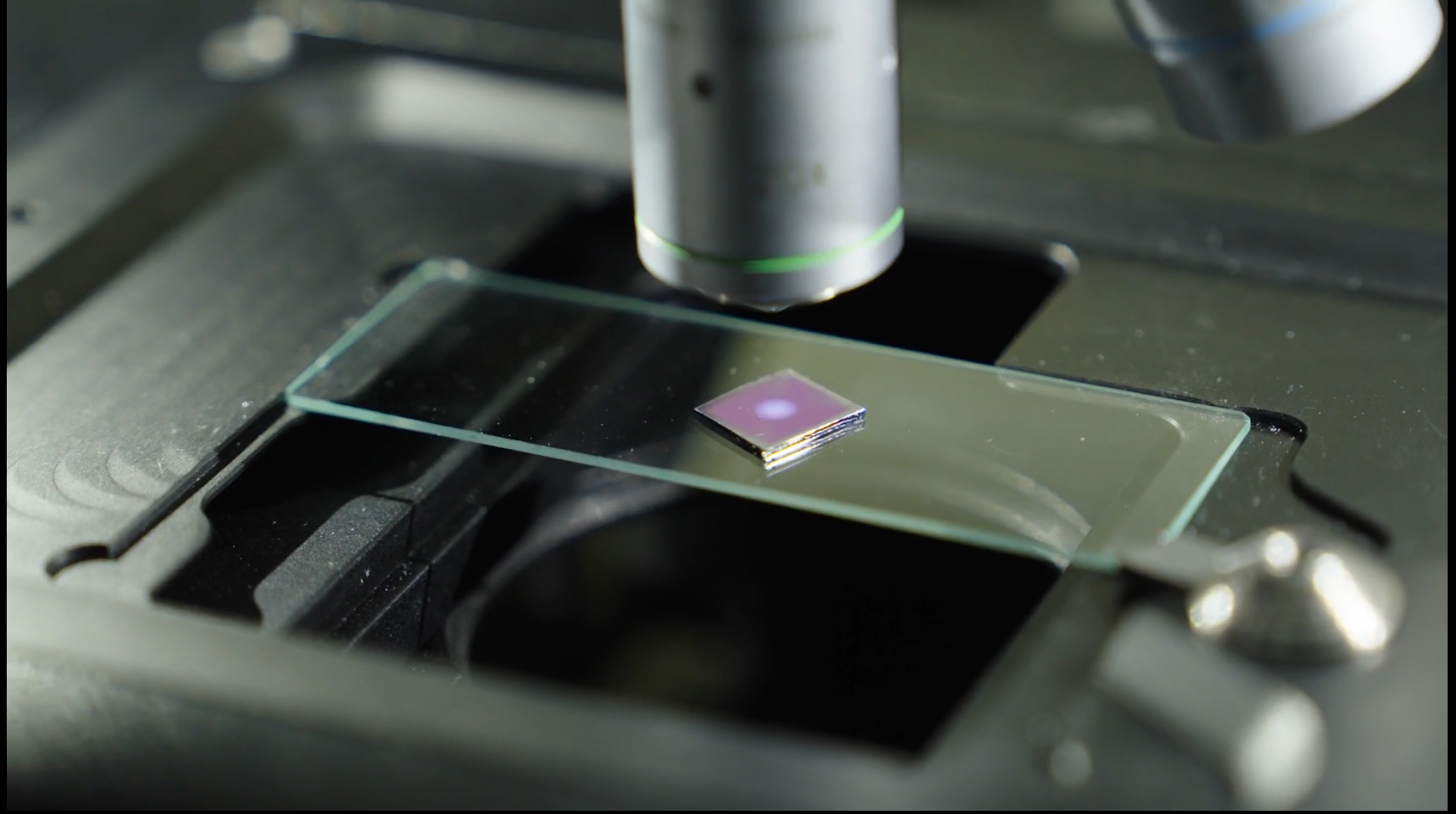

Nanoparticles and artificial intelligence can help researchers detect pollutants in water, soil and

Tiny particles bounce light around in a unique way, a property that researchers are using to detect…