Presidential corruption verdict shows just how flawed Brazil's justice system is

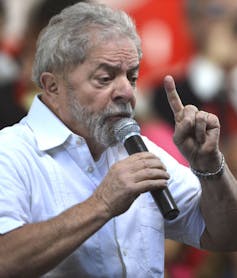

An appeals court ruling against popular Brazilian ex-president Lula has hotly divided Brazil. A legal scholar argues that this is a case of activist judges taking their anti-graft crusade too far.

On Jan. 24, a Brazilian appeals court upheld a criminal conviction against former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, rocking Brazil’s already turbulent political scene. The verdict, which confirms a 2017 ruling against the wildly popular Workers’ Party leader on corruption charges, could carry a prison sentence of up to 10 years.

It may also make Lula ineligible to run in Brazil’s October presidential election. The 72-year-old is currently his party’s nominee and a favorite to win the race.

Lula’s lawyer has deemed the appeals court verdict “a legal farce masquerading as justice.” Many Lula supporters agree, saying the ruling amounts to a preemptive presidential coup by the right wing.

His opponents, on the other hand, call the ruling a major victory against political corruption.

It’s a complicated case, but in my analysis, neither side has it quite right. As a Brazilian constitutional law professor and Supreme Court researcher, I see Lula’s trials as a marquee example of Brazil’s flawed and inconsistent justice system. It confirms that Brazilian judges are on a moral quest to “cleanse” politics – and they’re willing to bend the law to do it.

Brazil behind Lula

The Jan. 24 verdict has upended Brazilian politics. That’s because Lula is not simply a former president convicted of corruption.

Lula left office in 2010 after two four-year terms with an 80-percent approval rating. In 2009, Barack Obama called him “the most popular politician on Earth.

Eight years later, polls show Lula leading by 18 points over his closest rival in the 2018 presidential race, despite multiple recent indictments on graft charges.

The loyalty derives largely from the Lula administration’s success in markedly decreasing hunger and poverty in Brazil. As president Lula launched the Bolsa Família program, which gave cash to millions of poor families. He also created tuition incentives helped working-class students go to college and improved access to electricity.

Recently, though, reputation has been tarnished somewhat. Since 2012, the Supreme Court has convicted four Lula allies for orchestrating a sustained bribery scheme called ”Mensalão.“ The cabinet members and ministers paid members of congress 30,000 reais – roughly US$10,000 – each month in exchange for legislative support on key issues.

Lula was never charged in the Mensalão, and he claims he knew nothing about it.

The justice system against Lula?

He was not able to escape Operation Car Wash, a massive corruption investigation lead by the popular judge Sérgio Moro. Indeed, it was Moro who in 2017 convicted Lula of graft for receiving a free penthouse apartment from a construction company, OAS, which had benefited from illegal government contracts during Lula’s administration.

The Jan. 24 appeals court ruling upheld that conviction unanimously. A three-judge panel found the former president guilty on several grounds, and bolstered some charges largely unsubstantiated in the original ruling.

Mainly, they found that early in his administration Lula had used his political power to influence the board and leadership of Petrobras, Brazil’s state oil company. In 2003 and 2004, Petrobras went on to make numerous illegal infrastructure development contracts, with OAS and other firms.

The appellate judges determined that there was no need to prove how, specifically, Lula helped OAS, since it’s reasonable to believe that a sitting president would have known about and endorsed his subordinates’ illegal contracts scheme.

The judges also agreed that Lula and his wife, Marisa Letícia Lula da Silva, had shown suspicious interest in an apartment owned by OAS. Though they never purchased it or even lived there, the couple suggested specific renovations to the space. Those projects were completed.

Essentially, Brazilian courts have now twice found Lula guilty of corrupt dealings with OAS beyond any reasonable doubt. In legal terms, though, the shaky evidence shows only that something fishy was going on with that OAS apartment. For many Brazilians, "fishy” seems insufficient to disqualify a presidential front-runner.

The decision looks more dubious considering that Brazil’s current president, Michel Temer, dodged criminal prosecution for a September 2017 indictment after his chief of staff was caught leaving a business lunch with a briefcase full of hush money allegedly meant for Temer.

Brazil’s flawed judiciary

That still doesn’t prove that Lula’s prosecution is political. Frankly, the Brazilian judiciary is prone to inconsistencies and to ignoring the due process of law.

Brazil has the world’s third highest prison population, with some 660,000 incarcerated people. Around 35 percent of them have not yet been tried, and the vast majority of prisoners are poor, young black men facing lengthy sentences for charges that white defendants almost never see.

In other words, there is a punitive streak among Brazilian prosecutors and judges. Historically, though, the judiciary has gone easy on rich defendants with the best defense attorneys money could buy.

In a way, what Lula’s verdict shows is that the judiciary’s instinct to punish – normally reserved for pickpocketers and low-level drug dealers – has now been unleashed on some of Brazil’s most powerful people. The contrast with Temer’s lack of prosecution is another example of unequal treatment under the law.

Moralizing judges

When the Mensalão scandal exposed Brazil’s pervasive corruption, many citizens came to see the judiciary as the last democratic bastion in a mostly rotten republic. In doing so, they ignored its many flaws.

Worse still, it seems that judges like Moro and others, too, believe the idea that the criminal justice system alone can clean up politics.

And since the wheels of justice turn slowly in Brazil – where cases can take up to 12 years to conclude – judges as high as the Supreme Court have found ad hoc, unprecedented ways to rebuke politicians they believe to be corrupt.

They have barred ministers from taking office, suspended congressmen, imprisoned senators and even put legislators under house arrest – often without clear constitutional grounds or legal precedent for doing so. At bottom, the work of a judge is to apply established law or, when creating a new precedent, to do so with clear new rules.

These judicial interventions have unduly influenced Brazilian politics. So far, the Workers’ Party has seen more prosecution than other major party, though that seems to be changing.

All of this has increased the popular perception that Brazil’s court system is just as politicized as politics itself. As a result, confidence in the judiciary has been dropping steadily for years.

Lula’s lost appeal is the perfect distillation of what ails the Brazilian legal system. It is one part judicial activism in the name of anti-corruption, one part judicial disregard for legal precedents and due process. With the good intention of “fixing” politics, Brazil’s judges may be breaking the rule of law.

What they are not doing, I would argue, is staging a partisan judicial coup against the Workers’ Party.

Ultimately, Lula’s case will be again appealed and eventually decided by a higher court. That process could take many months. In the meantime, an electoral court must determine whether to let Lula run for president in October.

To do so, Brazilian judges will again find themselves deciding a profoundly political question: Would Lula’s candidacy strengthen or subvert Brazilian democracy?

Rubens Glezer does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…

Drug company ads are easy to blame for misleading patients and raising costs, but research shows the

Officials and policymakers say direct-to-consumer drug advertising encourages patients to seek treatments…

Nanoparticles and artificial intelligence can help researchers detect pollutants in water, soil and

Tiny particles bounce light around in a unique way, a property that researchers are using to detect…