Thanks to the North Carolina case, partisan gerrymandering's day of reckoning may soon be upon us

Judges in North Carolina just threw out the state's congressional district map. The decision could have major implications for the future of partisan gerrymandering across the US.

Gerrymandering was already shaping up to be an important issue this year, with huge implications for American democracy. But after the ruling this week on the North Carolina congressional map, the stakes have been raised still higher.

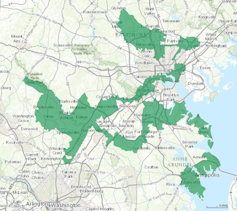

For the first time, a federal panel of judges ruled that a state’s map of its congressional districts was unconstitutional. The North Carolina map didn’t just give an advantage to Republicans – it manifested “invidious partisan intent.” The panel directed the state to draw the districts again by Jan. 24.

Politicians are always looking for partisan advantages, and the constitutional mandate to redraw district boundaries every 10 years provides an irresistible opportunity. When that mandate falls to a state legislature that is controlled by one party, well, you can imagine what those boundaries look like.

But sometimes parties go too far. They create maps that entrench that party in power, making it virtually impossible for the opposition to compete. When that happens, voters are effectively disenfranchised, and it becomes a constitutional question.

As the managing director of an institute dedicated to defending democracy, the North Carolina ruling leaves me hopeful that after this term of the Supreme Court, American elections might better reflect the will of the people.

Partisan vs. racial gerrymandering

The Supreme Court has acknowledged that partisan gerrymandering can be so egregious as to be “unlawful.” But they have punted on the question of how far is too far.

The court has repeatedly decided questions regarding racial gerrymandering – for example, when states “pack” minorities into a district to mitigate their political power. As a matter of fact, this is the second time the North Carolina map has been rejected. The first time was for racial gerrymandering.

But the court says it doesn’t have a “workable standard” to decide when partisan gerrymandering becomes unconstitutional. And without that, they fear that every decennial they will get 50 claims from every state’s aggrieved minority party.

This distinction between partisan and racial gerrymandering has always been slippery at best. Minorities vote overwhelmingly Democratic. But the distinction – and the mandate for minority representation in the Voting Rights Act of 1965 – gave partisans a useful justification for their actions. It also gave the courts a way to dodge this very thorny question. But it looks like this convenient distinction is crumbling before our eyes.

To the Supreme Court

Two cases before the Supreme Court this term directly confront partisan gerrymandering. As a result, continued punting looks very unlikely.

A Wisconsin case was appealed from a Federal District Court that ruled, for the first time, that the Republican-drawn state legislative map was over the line. The court’s opinion, written by a Reagan appointee, concluded that the map “intended to burden the representational rights of Democratic voters … by impeding their ability to translate their votes into legislative seats.” This conclusion is precisely what the Supreme Court will have to address.

Then just last month, the Supreme Court agreed to hear another case, this time from Maryland, where the Democrats are the party in charge. The decision to hear the case was itself a surprise, since the justices had already denied the plaintiffs’ request to expedite the appeal.

By hearing these cases at all, the justices are once again addressing the idea that state legislatures can act unlawfully, but with the Wisconsin case, they are also acknowledging at least the possibility that they may now have the “workable standard” they are looking for.

In Wisconsin, the decision by a three-judge panel rested on data showing that the Republican map led to a lot of wasted votes. These wasted votes were effectively irrelevant, because they were either well beyond the amount needed for victory, or not nearly close enough to overcome defeat.

Eric McGhee, from the Public Policy Institute of California, and Nicholas Stephanopoulos, from the University of Chicago Law School, argue that these wasted votes amount to an efficiency gap: the difference between the effective power of a Republican vote versus one from a Democrat. The larger the efficiency gap – that is, the greater percentage of wasted votes for one party versus the other – the more unfair and unconstitutional the map.

In oral arguments, Chief Justice John Roberts dismissed this measure as “sociological gobbledygook.” But if the court majority were looking for a way to show when partisan gerrymandering crosses the line and becomes unconstitutional, it might have found it.

What happens next?

With all this in play, it would have been difficult for the court to once again affirm the status quo. But now add the fact that a federal district court has once again broken the barrier.

But now comes the North Carolina opinion, which once again affirms that there is a line when partisan gerrymandering becomes unconstitutional, and that the courts have the right and duty to say when it is crossed. The state has said it plans to appeal to the Supreme Court. If the Supreme Court agrees, that would make three such cases.

If the Supreme Court does indeed rule for the plaintiffs in one or both cases, it would, in my view, have a significant and positive impact on American democracy. Establishing a legal standard for unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering would improve the contestability of elections. Americans would be more likely to believe their vote matters, and politicians would feel constrained to more accurately reflect their constituents’ values and interests.

Christopher Beem does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…

Former Harvard president Summers’ soft landing after Epstein revelations is case study of economics’

Despite repeated calls for the university to revoke his tenure, the economist held onto his teaching…

Fewer new moms are dying in Colorado – naloxone might be one reason why

The opioid reversal drug is distributed directly to new moms at many of Colorado’s birthing hospitals.