EPA’s new way of evaluating pollution rules hands deregulators a sledgehammer and license to ignore

In the world of cost benefit analysis, if an impact isn’t monetized, it doesn’t exist. A former EPA official explains what’s changing now and why it matters.

When I worked for the Environmental Protection Agency in the 2010s as an Obama administration appointee, I helped write and review dozens of regulations under the Clean Air Act. They included some groundbreaking rules, such as setting national air quality standards for ozone and fine particulate matter.

For each rule, we considered the costs to industry if the rule went into effect – and also the benefits to people’s health.

Study after study had demonstrated that being exposed to increased air pollution leads to more asthma attacks, more cardiovascular disease and people dying sooner than they would have otherwise. The flip side is obvious: Lower air pollution means fewer asthma attacks, fewer heart problems and longer lives.

To use this information in making decisions, we needed to have a way to compare the costs of additional pollution controls to industry, and ultimately, to consumers, against the benefits to public health. A balanced approach meant putting a dollar value on health benefits and weighing them against the seemingly more easily, though not always accurately, predicted costs of complying with the regulations.

We were able to make these decisions because environmental economists since the 1980s have developed and continually improved robust methodologies to quantify the costs to society of air pollution’s effect on human health, such as workdays lost and hospital visits.

Now, however, the Trump administration is dropping one whole side of that cost-benefit equation. The EPA wrote in January 2026 that it will stop quantifying the health benefits when assessing the monetary impact of new pollution regulations and regulation changes involving pollutants that contribute to ozone, or smog, and fine particulate matter, known as PM2.5.

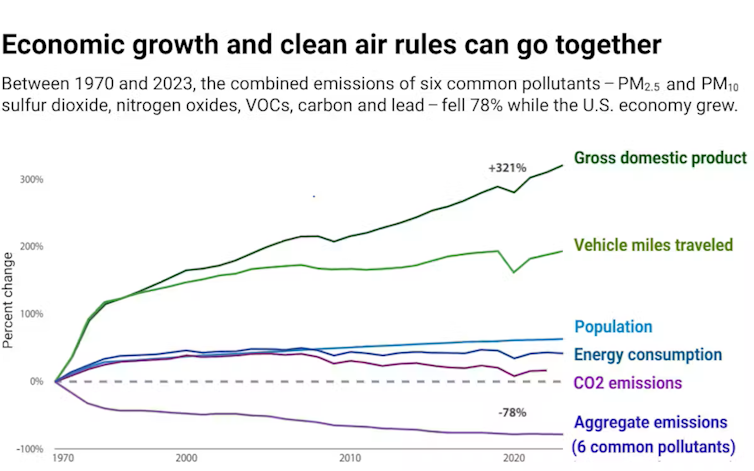

The result leaves government decision-makers without a way to clearly compare regulatory costs to health benefits. It will almost certainly lead to an increase in harmful pollution that America has made so much progress reducing over the decades.

Cost-benefit rules go back to Ronald Reagan

The requirement that agencies conduct a thorough cost-benefit analysis dates back to President Ronald Reagan’s efforts to cut regulatory costs in the 1980s.

In 1981, Reagan issued an executive order requiring cost-benefit analysis for every economically significant regulation. He wrote that, to the extent permitted by law, “Regulatory action shall not be undertaken unless the potential benefits to society for the regulation outweigh the potential costs to society.”

In 1993, President Bill Clinton issued another executive order, EO 12866, which to this day governs federal agency rulemaking. It states: “In deciding whether and how to regulate, agencies should assess all costs and benefits of available regulatory alternatives. … Costs and benefits shall be understood to include both quantifiable measures (to the fullest extent that these can be usefully estimated) and qualitative measures of costs and benefits that are difficult to quantify, but nevertheless essential to consider.”

Quantifying human health benefits

In response to these directives, environmental economists have generated rigorous, peer-reviewed and data-driven methods and studies to inform both sides of the cost-benefit equation over the past four decades.

Estimating costs seems like it would be relatively straightforward, even if not always precisely on the money. Industry provides the EPA with predictions of costs for control technology and construction. Public review processes allow other experts to opine on those estimates and offer additional information.

For a system as complex as the power grid, however, it’s a lot more complicated. Starting in the 1990s, the EPA developed the Integrated Planning Model, a complex, systemwide model used to evaluate the cost and emissions impacts of proposed policies affecting power plants. That model has been improved and updated, and has repeatedly undergone peer review in the years since.

On the health benefits side, in 2003, EPA economists developed the Environmental Benefits Mapping and Analysis Program, which uses a wide range of air quality data to assess changes in health effects and estimates the monetized value of avoiding those health effects.

For example, when the EPA was developing carbon pollution standards for power plants in 2024, it estimated that the rule would cost industry US$0.98 billion a year while delivering $6.3 billion in annual health benefits. The benefit calculation includes the value of avoiding approximately 1,200 premature deaths; 870 hospital and emergency room visits; 1,900 cases of asthma onset; 360,000 cases of asthma symptoms; 48,000 school absence days; and 57,000 lost work days.

The EPA has used these toolsets and others for many regulatory decisions, such as determining how protective air quality standards should be or how much mercury coal-fired power plants should be permitted to emit. Its reports have documented continual refinement of modeling tools and use of more comprehensive data for calculating both costs and benefits.

Not every health benefit can be monetized, as the EPA often acknowledges in its regulatory impacts assessments. But we know from years of studies that lower levels of ozone and fine particles in the air we breathe mean fewer heart attacks, asthma cases and greater longevity.

The Trump EPA’s deregulation sledgehammer

The U.S. EPA upended the practice of monetizing health costs in January 2026. In a few paragraphs of a final rulemaking about emissions from combustion turbines, the EPA stated that it would no longer quantify the health benefits associated with reduced exposure to ozone and PM2.5.

The agency said that it does not deny that exposure to air pollution adversely affects human health, including shortening people’s lives. But, it says, it now believes the analytical methods used to quantify health benefits from reduced air pollution are not sufficiently supported by the underlying science and have provided a false sense of precision.

As a result, the EPA decided it will no longer include any quantification of benefits, though it will consider qualitative effects.

Understanding the qualitative effects is useful. But for the purposes of an actual rule, what matters is what gets quantified.

The new decision hands a sledgehammer to deregulators because in the world of cost-benefit analysis, if an impact isn’t monetized, it doesn’t exist.

What does this mean?

Under this new approach, the EPA will be able to justify more air pollution and less public health protection when it issues Clean Air Act rules.

Analysis of new or revised rules under the Clean Air Act will explain how much it would cost industry to comply with control requirements, and how much that might increase the cost of electricity, for example. But they will not balance those costs against the very real benefits to people associated with fewer hospital or doctor visits, less medication, fewer missed school or workdays, and longer life.

Costs will easily outweigh benefits in this new format, and it will be easy for officials to justify ending regulations that help improve public health across America.

I know the idea of putting a dollar value on extra years of human life can be uncomfortable. But without it, the cost for industry to comply with the regulation – for reducing power plant emissions that can make people sick, for example – is the only number that will count.

Janet McCabe worked in the U.S. EPA Office of Air and Radiation from 2009 to 2017 and was EPA's deputy administrator from 2021 to 2024. She is a volunteer with the Environmental Protection Network.

Read These Next

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…

Why US third parties perform best in the Northeast

Many Americans are unhappy with the two major parties but seldom support alternatives. New England is…

Abortion laws show that public policy doesn’t always line up with public opinion

Polls indicate majority support for abortion rights in most states, but laws differ greatly between…