‘We want you arrested because we said so’ – how ICE’s policy on raiding whatever homes it wants viol

Since the republic’s beginning, it has been uncontested law that to invade someone’s home, the government needs a warrant reviewed and signed by a judicial officer. ICE is turning that law on its head.

As Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, agents continued to use aggressive and sometimes violent methods to make arrests in its mass deportation campaign, including breaking down doors in Minneapolis homes, a bombshell report from the Associated Press on Jan. 21, 2026, said that an internal ICE memo – acquired via a whistleblower – asserted that immigration officers could enter a home without a judge’s warrant. That policy, the report said, constituted “a sharp reversal of longstanding guidance meant to respect constitutional limits on government searches.”

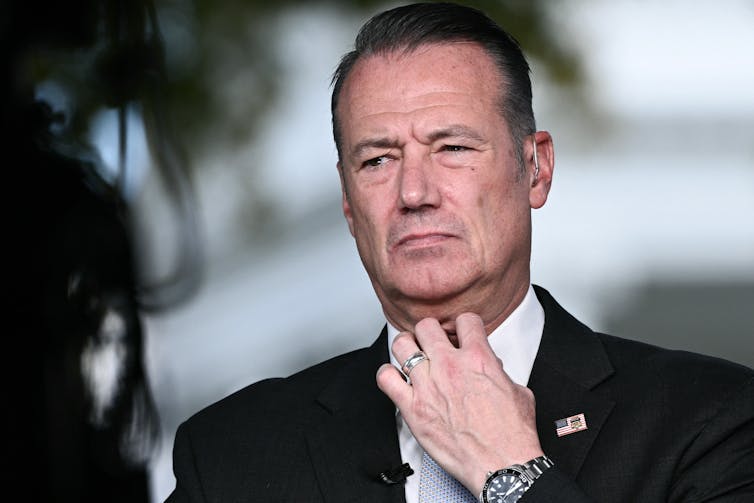

Those limits have long been found in the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Politics editor Naomi Schalit interviewed Dickinson College President John E. Jones III, a former federal judge appointed by President George W. Bush and confirmed unanimously by the U.S. Senate in 2002, for a primer on the Fourth Amendment, and what the changes in the ICE memo mean.

Okay, I’m going to read the Fourth Amendment – and then you’re going to explain it to us, please! Here goes:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” Can you help us understand what that means?

Since the beginning of the republic, it has been uncontested that in order to invade someone’s home, you need to have a warrant that was considered, and signed off on, by a judicial officer. This mandate is right within the Fourth Amendment; it is a core protection.

In addition to that, through jurisprudence that has evolved since the adoption of the Fourth Amendment, it is settled law that it applies to everyone. That would include noncitizens as well.

What I see in this directive that ICE put out, apparently quite some time ago and somewhat secretly, is something that, to my mind, turns the Fourth Amendment on its head.

What does the Fourth Amendment aim to protect someone from?

In the context of the ICE search, it means that a person’s home, as they say, really is their castle. Historically, it was meant to remedy something that was true in England, where the colonists came from, which was that the king or those empowered by the king could invade people’s homes at will. The Fourth Amendment was meant to establish a sort of zone of privacy for people, so that their papers, their property, their persons would be safe from intrusion without cause.

So it’s essentially a protection against abuse of the government’s power.

That’s precisely what it is.

Has the accepted interpretation of the Fourth Amendment changed over the centuries?

It hasn’t. But Fourth Amendment law has evolved because the framers, for example, didn’t envision that there would be cellphones. They couldn’t understand or anticipate that there would be things like cellphones and electronic surveillance. All those modalities have come into the sphere of Fourth Amendment protection. The law has evolved in a way that actually has made Fourth Amendment protections greater and more wide-ranging, simply because of technology and other developments such as the use of automobiles and other means of transportation. So there are greater protected zones of privacy than just a person’s home.

ICE says it only needs an administrative warrant, not a judicial warrant, to enter a home and arrest someone. Can you briefly describe the difference and what it means in this situation?

It’s absolutely central to the question here. In this context, an administrative warrant is nothing more than the folks at ICE headquarters writing something up and directing their agents to go arrest somebody. That’s all. It’s a piece of paper that says ‘We want you arrested because we said so.’ At bottom that’s what an administrative warrant is, and of course it hasn’t been approved by a judge.

This authorized use of administrative warrants to circumvent the Fourth Amendment flies in the face of their limited use prior to the ICE directive.

A judicially approved warrant, on the other hand, has by definition been reviewed by a judge. In this case, it would be either a U.S. magistrate judge or U.S. district judge. That means that it would have to be supported by probable cause to enter someone’s residence to arrest them.

So the key distinction is that there’s a neutral arbiter. In this case, a federal judge who evaluates whether or not there’s sufficient cause to – as is stated clearly in the Fourth Amendment – be empowered to enter someone’s home. An administrative warrant has no such protection. It is not much more than a piece of paper generated in a self-serving way by ICE, free of review to substantiate what is stated in it.

Have there been other kinds of situations, historically, where the government has successfully proposed working around the Fourth Amendment?

There are a few, such as consent searches and exigent circumstances where someone is in danger or evidence is about to be destroyed. But generally it’s really the opposite and cases point to greater protections. For example, in the 1960s the Supreme Court had to confront warrantless wiretapping; it was very difficult for judges in that age who were not tech-savvy to apply the Fourth Amendment to this technology, and they struggled to find a remedy when there was no actual intrusion into a structure. In the end, the court found that intrusion was not necessary and that people’s expectation of privacy included their phone conversations. This of course has been extended to various other means of technology including GPS tracking and cellphone use generally.

What’s the direction this could go in at this point?

What I fear here – and I think ICE probably knows this – is that more often than not, a person who may not have legal standing to be in the country, notwithstanding the fact that there was a Fourth Amendment violation by ICE, may ultimately be out of luck. You could say that the arrest was illegal, and you go back to square one, but at the same time you’ve apprehended the person. So I’m struggling to figure out how you remedy this.

John E. Jones III is affiliated with Keep Our Republic’s Article Three Coalition.

Read These Next

Arming a Kurdish insurgency would be a risky endeavor – for both the US and Iran’s minority Kurds

Washington has long worked with Kurdish groups in the Middle East. But without sufficient support, encouraging…

War in Middle East brings uncertainty and higher energy costs to already weakening US economy

Risks for the US economy grow as the war in the Middle East continues to escalate.

Venezuela’s fragile forests face rising risks as US pushes for oil and critical minerals and illegal

The Orinoco Basin is one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. It’s also rich in oil, gold…