Trump’s National Guard deployments reignite 200-year-old legal debate over state vs. federal power

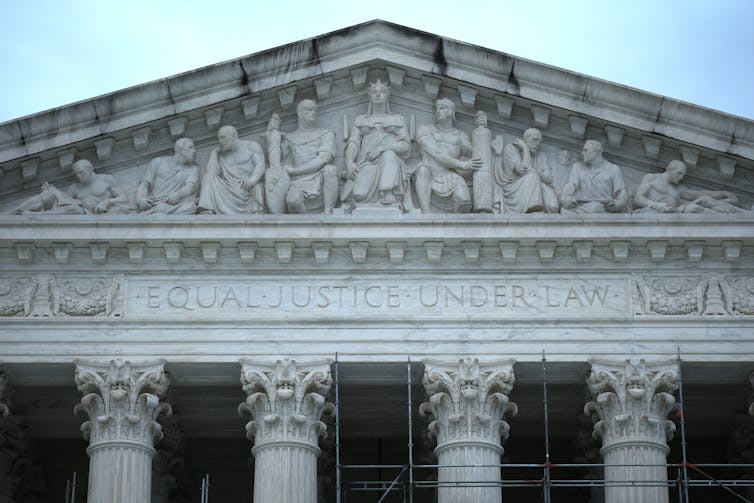

The conflicts over President Trump’s deployment of National Guard troops to Illinois and Oregon hinge on a question as old as the Constitution itself: Where does federal power end and state authority begin?

If you’re confused about what the law does and doesn’t allow the president to do with the National Guard, that’s understandable.

As National Guard troops landed in Portland, Oregon, in late September 2025, the state’s lawyers argued that the deployment was a “direct intrusion on its sovereign police power.”

Days before, President Donald Trump, calling the city “a war zone,” had invoked a federal law allowing the government to call up the Guard during national emergencies or when state authorities cannot maintain order.

The conflict throws into relief a question as old as the Constitution itself: Where does federal power end and state authority begin?

One answer seems to appear in the 10th Amendment’s straightforward language: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” This text is considered to be the constitutional “hook” for federalism in our democracy.

The founders, responding to anti-Federalist anxieties about an overbearing central government, added this language to emphasize that the new government possessed only limited powers. Everything else – including the broad “police power” to regulate health, safety, morals and general welfare – remained with the states.

Yet from the beginning, the text has generated plenty of confusion. Is the 10th Amendment merely a “truism,” as Justice Harlan Fiske Stone wrote in 1941 in United States v. Darby, restating the Constitution’s structure of limited powers? Or does it describe concrete powers held by the states?

Turns out, there’s no simple answer, not even from the nation’s highest court. Over the years, the Supreme Court has treated the 10th Amendment like the proverbial magician’s hat, sometimes pulling robust state powers from its depths, other times finding it empty.

10th Amendment’s broad range

The arguments over the 10th Amendment for almost 200 years have applied not only to the National Guard but to questions about how the federal and state governments share powers over everything from taxation to government salaries, law enforcement and regulation of the economy.

For much of the 19th century, the 10th Amendment remained dormant. The federal government’s weakness and limited ambitions, especially on the slavery question, meant that boundaries were rarely tested before the courts.

The New Deal era brought this equilibrium crashing down.

The Supreme Court initially resisted the expansion of federal power, striking down laws banning child labor in Hammer v. Dagenhart in 1918, setting a federal minimum wage in 1923 in Adkins v. Children’s Hospital, and offering farmers subsidies in U.S. v. Butler in 1937. All these decisions were based on the 10th Amendment.

But this resistance wore down in the face of economic crisis and political pressure. By the time of the Darby case in 1941, which concerned the Fair Labor Standards Act and Congress’ power to regulate many aspects of employment, the court had relegated the 10th Amendment to “truism” status: The Amendment, wrote Stone, did nothing more than restate the relationship between the national and state governments as it had been established by the Constitution before the amendment.

The 1970s marked an unexpected revival. In the 1976 decision in National League of Cities v. Usery, a dispute over whether Congress could directly exercise control over minimum wage and overtime pay for state and local government employees, the court held that Congress could not use its commerce power to regulate state governments.

But that principle was abandoned nine years later, with the court doubling back on its position. Now, if the states wanted protection from federal overreach, they would have to seek it through the political process, not judicial intervention.

Yet less than a decade later, the court reversed course again. The modern federalism renaissance began in the ’90s with a pair of divided opinions stating that the federal government cannot force the states to enforce federal regulatory programs: this was the “anti-commandeering principle.”

The 10th Amendment’s meandering path

In recent decades, the court, led by Chief Justice John Roberts, has invoked the amendment to protect state power in varied, even surprising contexts: states’ entitlement to federal Medicaid spending; state authority over running elections, despite patterns of voter exclusion; even legalization of sports gambling.

On the other hand, in 2024, Colorado was barred by the court from excluding Trump from the presidential ballot as part of its power to administer elections.

That brings us back to the present, where Trump has deployed National Guard troops to Los Angeles to quell protests against immigration enforcement, and bids to send them to Portland and Chicago as well.

From the point of view of federalism, two factors lend this conflict some constitutional complexity.

One is the National Guard’s dual state-federal character. Most Guard mobilizations, including disaster relief, take place under Title 32 of the U.S. Code, which maintains state control of troops with federal funding.

By contrast, Title 10 allows the president to assert federal control over Guard units in case of “a rebellion or danger of a rebellion” against the government or where “the President is unable with the regular forces to execute the laws of the United States.”

The other factor is political.

Since World War II, the National Guard has been deployed only 10 times by presidents, mostly in support of racial desegregation and the protection of civil rights. All but one of these mobilizations came at the governor’s request – the lone exception, pre-Trump, being President Dwight Eisenhower’s 1957 mobilization of the Arkansas National Guard to desegregate schools in Little Rock over the wishes of Gov. Orval Faubus.

In sharp contrast, Trump has now attempted three times to send troops to large cities over the explicit objection of Democratic governors. Such is the case in Portland.

National Guard deployments and constitutional stakes

Oregon’s lawsuit argues that there is no national emergency in the city, and that deploying Guard troops to the state without Gov. Tina Kotek’s consent – indeed, over her explicit objection – and absent the extraordinary circumstances that might justify Title 10 federalization, is illegal. The National Guard, asserts the lawsuit, remains a state institution that federal authorities cannot commandeer.

The two deployments, in Oregon and Illinois, are making their way through the federal courts, and the Trump administration has asked the Supreme Court to intervene to authorize the deployments. What the court will do, if the cases reach it, is uncertain. Roberts has proved willing to invoke state sovereignty in some contexts while rejecting it in others.

For now, the court has upheld several Trump administration actions while constraining others, suggesting a jurisprudence driven more by specific contexts than categorical rules.

Whether Oregon’s challenge succeeds may depend less on the long and changing history of 10th Amendment doctrine than on how the court views immigration enforcement, presidential authority and the consequences of Trump’s frequent invocations of emergency power for American democracy.

Andrea Katz does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Crowdfunded generosity isn’t taxable – but IRS regulations haven’t kept up with the growth of mutual

Some Americans are discovering that monetary help they received from friends, neighbors or even strangers…

What is Bluetooth and how does it work?

Did you know that your wireless earbuds contain a tiny radio transmitter?

Picky eating starts in the womb – a nutritional neuroscientist explains how to expand your child’s p

While genes do influence some food preferences, positive experiences can help make new tastes easier…