Orwell’s opposition to totalitarianism was rooted in his support for freeing workers from poverty an

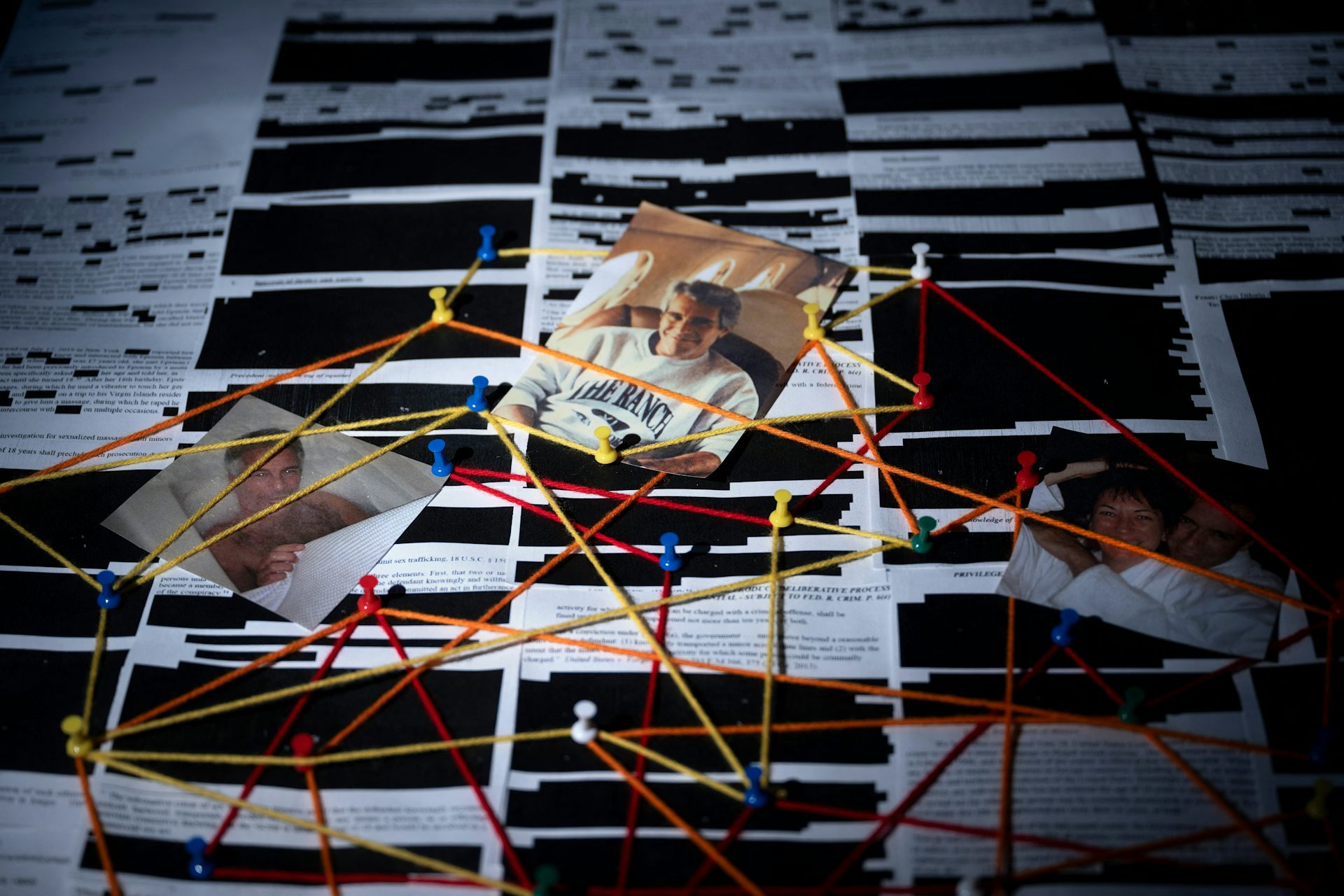

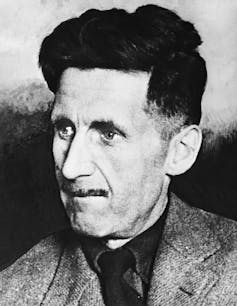

George Orwell, the author of two classic anti-totalitarian, pro-freedom novels from the 1940s, was a democratic socialist decades before popular political progressives in the US espoused the ideology.

George Orwell’s dystopian novels “Animal Farm” and “1984” have remained popular in the U.S. ever since their initial publication in the 1940s.

What’s less well known is that in the years before the publication of “Animal Farm” and “1984,” Orwell’s writing often focused primarily on other themes including work, poverty, anti-imperialism and democratic socialism.

In fact, Orwell remained a committed democratic socialist until his death in 1950.

“Animal Farm” tells the tale of a group of farm animals who take ownership of their farm from their human master by means of rebellion, but who eventually end up re-enslaved by the farm’s pigs. “1984” tells the story of one man’s failed attempt to resist totalitarian rule in a hypothetical future dictatorship set in Orwell’s home country of England.

Part of these books’ initial appeal came from their critiques of Soviet communism as the U.S. was entering the Cold War. Part of why the books seem to have remained popular are their anti-totalitarian and pro-freedom messages, which have been praised by people across the U.S. political spectrum.

Orwell, who died of tuberculosis at age 46, is a writer famous for the ideas that preoccupied him in the final years of his life. His journey to those ideas via his thinking about work, poverty and democratic socialism, among other themes, may surprise those familiar with only his dystopian fiction.

Communism and socialism not synonymous

Orwell’s democratic socialism may surprise some Americans for at least two reasons.

First, when many Americans talk about politics, they often treat communism and socialism as interchangeable terms. How could Orwell, the great satirist of Soviet communism, have been a socialist?

The answer is that communism and socialism are not synonymous.

Orwell denied that Soviet communism was a form of socialism. Instead, he saw Soviet communism as totalitarianism merely masquerading as socialism.

Orwell claimed in his 1937 book, “The Road to Wigan Pier,” that “Socialism means justice and common decency” and a commitment to “the overthrow of tyranny.” Elsewhere in the same book, he maligned communism’s anti-democratic behavior as like “sawing off the branch you are sitting on.”

A second reason that Orwell’s commitment to democratic socialism may surprise some is because in the U.S., democratic socialism is often associated with the nation’s most left-leaning political figures, such as Sen. Bernie Sanders, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani. And Orwell is often not viewed in popular imagination as a political progressive.

Yet, by American standards, Orwell was very politically progressive. He argued in “The Lion and the Unicorn” that his home country of England ought to nationalize mines, railways, banks and major industries. He also argued for limits on income inequality. Some of these policies run to the left of even most U.S. democratic socialists.

For Orwell, such left-leaning economic policies were not only compatible with, but required, a strong commitment to the central pillars of democracy, such as intellectual freedom, free speech, a free press and genuine rule by the people.

I think the best way to understand how these aspects of Orwell’s political views came together is to look at the evolution of his writing.

Work and poverty

Two of the most important themes in Orwell’s first decade as a professional writer, the 1930s, are work and poverty.

These are what he focused on most in his first book, the autobiographical “Down and Out in Paris and London,” published in 1933. There he recounts his experiences living among the poor and unemployed in France and England in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

The book is full of pithy insights, such as “poverty frees people from ordinary standards of behavior, just as money frees people from work,” and “the average millionaire is only the average dishwasher dressed in a new suit.”

The latter quote highlights one of the key ethical and political messages of “Down and Out”: It is primarily social and political circumstances, and not moral character, that separates the rich from the poor.

Another key theme in “Down and Out” is that without a certain amount of leisure, people are incapable of doing certain kinds of thinking.

For example, Orwell argued that the reason the kitchen staff in French restaurants had not gone on strike or formed a union was because “they do not think, because they have no leisure for it; their life has made slaves of them.”

Orwell blamed the owners of such establishments for exploiting their workers. As he saw it, at most upscale restaurants “the staff work more and the customers pay more” and “no one benefits except the proprietor.”

In multiple novels and works of nonfiction in the 1930s, Orwell continued to explore the idea that social and political circumstances robbed people of the time they needed to engage in tasks like serious thinking and writing.

Imperialism and democratic socialism

One of Orwell’s earliest and most enduring political commitments was anti-imperialism – opposition to extending national power by means of colonialization or military force.

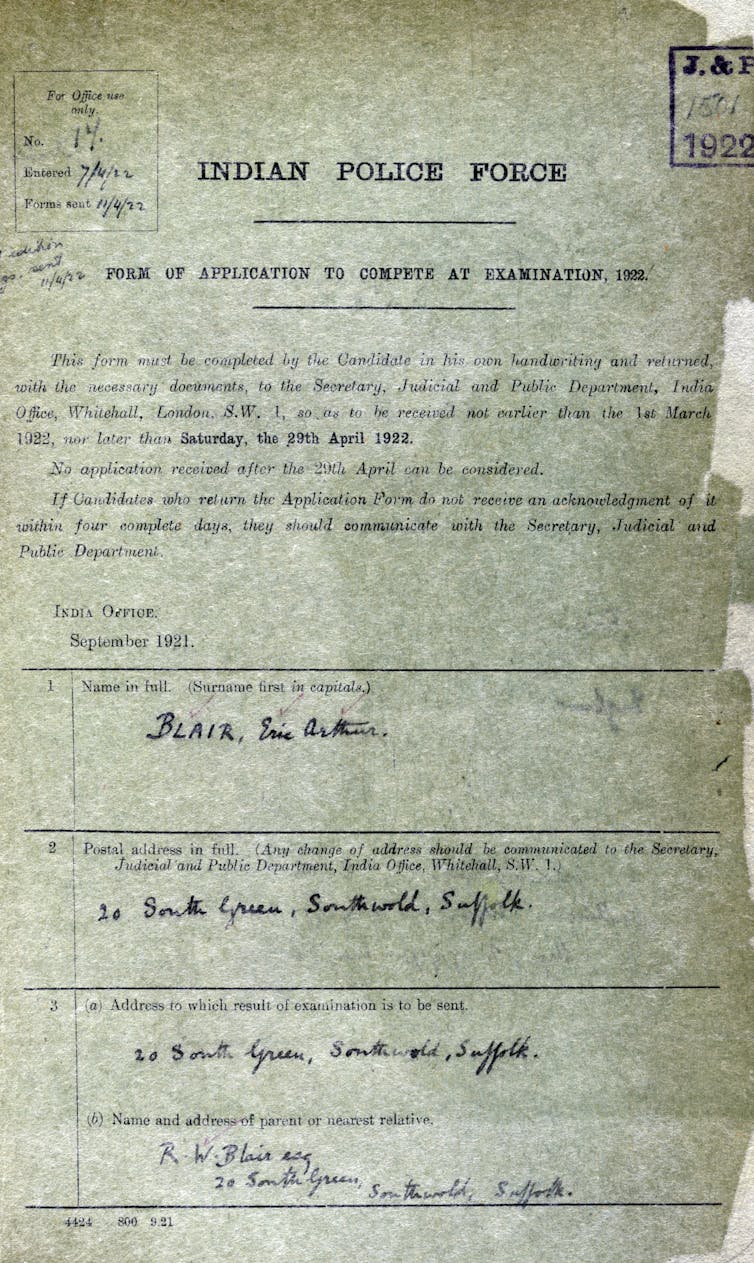

Orwell was of English and French descent. He was raised in England, but born in India in 1903. His father worked for the British Civil Service, which at the time exercised administrative control over India as a British colony.

Following his father’s footsteps, he spent five years working for the Imperial Police in Burma, now Myanmar. He came away from that experience with a deep hatred of imperialism. He drew upon this in his novel “Burmese Days” and his essays “A Hanging” and “Shooting an Elephant.”

In “The Road to Wigan Pier,” he wrote, “I hated the imperialism I was serving with a bitterness which I probably cannot make clear.”

“Wigan Pier” also displays Orwell’s commitment to democratic socialism. In the book’s first half, he reports on the dismal working and living conditions of the poor and unemployed in northern England. In the second half, he uses that material to make a case for democratic socialism.

In Orwell’s view, in deciding whether to embrace democratic socialism one had “to decide whether things at present are tolerable or not tolerable.” He concluded that present conditions were not tolerable and that democratic socialism was the way to make things better.

Propaganda and totalitarianism

Orwell developed into a sharp critic of Soviet Russia after witnessing how they used propaganda to mislead much of Europe about the Spanish Civil War. He discussed this in his book “Homage to Catalonia,” which recounts his time during the Spanish Civil War as a volunteer soldier fighting with the Spanish left against Gen. Francisco Franco, who would go on to become the country’s longtime dictator.

From Orwell’s perspective, communism highlighted the risks of how socialist revolution could go wrong. He thought that, without care, attempts at socialist revolution could create opportunities for a new form of oppression through totalitarianism.

He saw that totalitarianism was not limited to either the political left or right. Soviet communism represented left-wing totalitarianism, while Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy represented right-wing totalitarianism.

Thus, a major preoccupation in his final years was trying to warn people about the risks of falling into totalitarianism during times of political upheaval. Orwell wanted radical political change, but the change he wanted was in the service of increasing freedom and democracy, not decreasing it.

“Animal Farm” is a story about falling into autocracy. “1984” is a story about just how much autocracy can take from us.

But the things Orwell wanted to preserve, such as freedom of the mind, were also things that he thought were at risk from circumstances like poverty, oppressive working conditions and imperialism.

Research for this article was supported by a faculty fellowship from the Douglas A. Fraser Center for Workplace Issues at Wayne State University.

Read These Next

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

After a 32-hour shift in Pittsburgh, I realized EMTs should be napping on the job

A paramedic and university professor shares data about how strategic napping could help his own health…

Trump administration axed nutrition education program that saved more money than it cost, even as go

Every dollar spent on community health education through SNAP-ED saved an estimated $10.64 in Medicaid…