The World Court just ruled countries can be held liable for climate change damage – what does that m

The ruling stems from the harm island nations are suffering as sea level rises, and it opens a door for future claims for reparations. But getting to that point isn’t so simple.

The International Court of Justice issued a landmark advisory opinion in July 2025 declaring that all countries have a legal obligation to protect and prevent harm to the climate.

The court, created as part of the United Nations in 1945, affirmed that countries must uphold existing international laws related to climate change and, if they fail to act, could be held responsible for damage to communities and the environment.

The opinion opens a door for future claims by countries seeking reparations for climate-related harm.

But while the ruling is a big global story, its legal effect on the U.S. is less clear. We study climate policies, law and solutions. Here’s what you need to know about the ruling and its implications.

Why island nations called for a formal opinion

The ruling resulted from years of grassroots and youth-led organizing by Pacific Islanders. Supporters have called it “a turning point for frontline communities everywhere.”

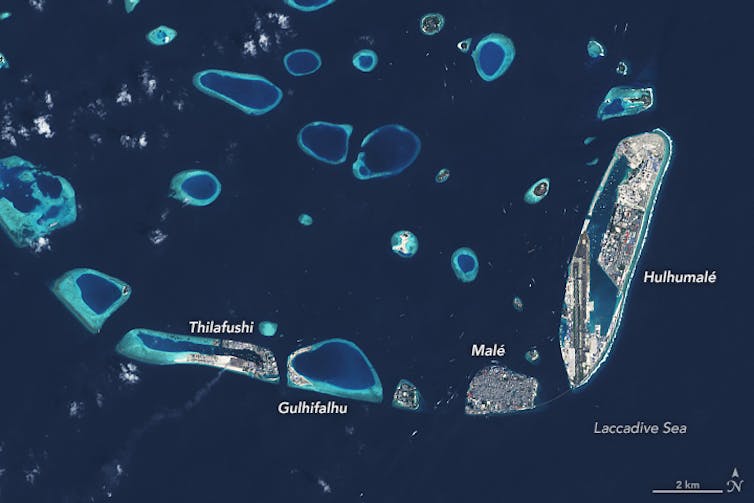

Small island states like Vanuatu, Tuvalu, Barbados and others across the Pacific and Caribbean are among the most vulnerable to climate change, yet they have contributed little to global emissions.

For many of them, sea-level rise poses an existential threat. Some Pacific atolls sit just 1 to 2 meters above sea level and are slowly disappearing as waters rise. Saltwater intrusion threatens drinking water supplies and crops.

Their economies depend on tourism, agriculture and fishing, all sectors easily disrupted by climate change. For example, coral reefs are bleaching more often and dying due to ocean warming and acidification, undermining fisheries, marine biodiversity and economic sectors such as tourism.

When disasters hit, the cost of recovery often forces these countries to take on debt. Climate change also undermines their credit ratings and investor confidence, making it harder to get the money to finance adaptive measures.

Tuvalu and Kiribati have discussed digital nationhood and leasing land from other countries so their people can relocate while still retaining citizenship. Some projections suggest nations like the Maldives or Marshall Islands could become largely uninhabitable within decades.

For these countries, sea-level rise is taking more than their land – they’re losing their history and identity in the process. The idea of becoming climate refugees and separating people from their homelands can be culturally destructive, emotionally painful and politically fraught as they move to new countries.

More than a nonbinding opinion

The International Court of Justice, commonly referred to as the ICJ or World Court, can help settle disputes between states when requested, or it can issue advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by authorized U.N. bodies such as the General Assembly or Security Council. The advisory opinion process allows its 15 judges to weigh in on abstract legal issues – such as nuclear weapons or the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories – without a formal dispute between states.

While the court’s advisory opinions are nonbinding, they can still have a powerful impact, both legally and politically.

The rulings are considered authoritative statements regarding questions of international law. They often clarify or otherwise confirm existing legal obligations that are binding.

What the court decided

The ICJ was asked to weigh in on two questions in this case:

“What are the obligations of States under international law to ensure the protection of the climate system … from anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases?”

“What are the legal consequences under these obligations for States where they, by their acts and omissions, have caused significant harm to the climate system?”

In its 140-page opinion, the court cited international treaties and relevant scientific background to affirm that obligations to protect the environment are indeed a matter of international environmental law, international human rights law and general principles of state responsibility.

The decision means that in the authoritative opinion of the international legal community, all countries are under an obligation to contribute to the efforts to reduce global greenhouse emissions.

To the second question, the court found that in the event of a breach of any such obligation, three additional obligations arise:

The country in breach of its obligations must stop its polluting activity, which would mean excess greenhouse gas emissions in this case.

It must ensure that such activities do not occur in the future.

It must make reparations to affected states in terms of cleanup, monetary payment and apologies.

The court affirmed that all countries have a legal duty under customary international law, which refers to universal rules that arise from common practices among states, to prevent harm to the climate. It also clarified that individual countries can be held accountable, even in a crisis caused by many countries and other entities. And it emphasized that countries that have contributed the most to climate change may bear greater responsibility for repairing the damage under an international law doctrine called “common but differentiated responsibility,” which is commonly found in international treaties concerning the environment.

While the ICJ’s opinion doesn’t assign blame to specific countries or trigger direct reparations, it may provide support for future legal action in both international and national courts.

What does the ICJ opinion mean for the US?

In the U.S., this advisory opinion is unlikely to have much legal impact, despite a long-standing constitutional principle that “international law is part of U.S. law.”

U.S. courts rarely treat international law that has not been incorporated into domestic law as binding. And the U.S. has not consented to ICJ jurisdiction in previous climate cases.

Contentious cases before international tribunals can be brought by one country against another, but they require the consent of all the countries involved. So there is little chance that the United States’ responsibility for climate harms will be adjudicated by the World Court anytime soon.

Still, the court’s opinion sends a clear message: All countries are legally obligated to prevent climate harm and cannot escape responsibility simply because they aren’t the only nation to blame.

The unanimous ruling is particularly remarkable given the current hostile political climate in the United States and other industrial nations around climate change and responses to it. It represents a particularly forceful statement by the international community that the responsibility to ensure the health of the global environment is a legal duty held by the entire world.

The takeaway

The ICJ’s advisory opinion marks a turning point in the global effort to hold countries responsible for climate change.

Vulnerable countries now have a more concrete, legally grounded base to claim rights and press for accountability against historical and ongoing climate harm – including financial claims.

How it will be used in the coming years remains unclear, but the opinion gives small island states in particular a powerful narrative and a legal tool set.

Lauren Gifford receives funding from the National Science Foundation and the US Department of Agriculture.

Daimeon Shanks-Dumont does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Supreme Court rules against Trump’s emergency tariffs – but leaves key questions unanswered

The ruling strikes down most of the Trump administration’s current tariffs, with more limited options…

Colorado has high levels of radon, which can cause lung cancer – here’s how to lower your risk

Only 50% of Colorado homes have been tested for radon.

Last nuclear weapons limits expired – pushing world toward new arms race

The expiration of the New START treaty has the US and Russia poised to increase the number of their…