What the Supreme Court ruling against ‘universal injunctions’ means for court challenges to presiden

The Supreme Court just made it harder for judges to block presidential policies nationwide, but lawmakers hold the key to changing that.

When presidents have tried to make big changes through executive orders, they have often hit a roadblock: A single federal judge, whether located in Seattle or Miami or anywhere in between, could stop these policies across the entire country.

But on June 27, 2025, the Supreme Court significantly limited this judicial power. In Trump v. CASA Inc., a 6-3 majority ruled that federal courts likely lack the authority to issue “universal injunctions” that block government policies nationwide. The ruling means that going forward federal judges can generally only block policies from being enforced against the specific plaintiffs who filed the lawsuit, not against everyone in the country.

The ruling emerged from a case challenging President Trump’s executive order attempting to end birthright citizenship. While three federal courts had blocked the policy nationwide, the Supreme Court allowed it to proceed against anyone who isn’t a named plaintiff in the lawsuits. This creates a legal environment where the same government policy can be simultaneously blocked for some people but enforced against others.

Crucially, the court based its decision on interpreting the Judiciary Act of 1789 – not the Constitution – meaning Congress could restore this judicial power simply by passing new legislation.

But what exactly are these injunctions, and why do they matter to everyday Americans?

Immediate, irreparable harm

When the government creates a policy that might violate the Constitution or federal law, affected people can sue in federal court to stop it. While these lawsuits work their way through the courts – a process that often takes years – judges can issue what are called “preliminary injunctions” to temporarily pause the policy if they determine it might cause immediate, irreparable harm.

A “nationwide” injunction – sometimes called a “universal” injunction – goes further by stopping the policy for everyone across the country, not just for the people who filed the lawsuit.

Importantly, these injunctions are designed to be temporary. They merely preserve the status quo until courts can fully examine the case’s merits. But in practice, litigation proceeds so slowly that executive actions blocked by the courts often expire when successor administrations abandon the policies.

More executive orders, more injunctions

Nationwide injunctions aren’t new, but several things have made them more contentious recently.

First, since a closely divided and polarized Congress rarely passes major legislation anymore, presidents rely more on executive orders to get substantive things done. This creates more opportunities to challenge presidential actions in court.

Second, lawyers who want to challenge these orders got better at “judge shopping” – filing cases in districts where they’re likely to get judges who agree with their client’s views.

Third, with growing political division, both parties used these injunctions more aggressively whenever the other party controls the White House.

Affecting real people

These legal fights have tangible consequences for millions of Americans.

Take DACA, the common name for the program formally called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which protects about 500,000 young immigrants from deportation. For more than 10 years, these young immigrants, known as “Dreamers,” have faced constant uncertainty.

That’s because, when President Barack Obama created DACA in 2012 and sought to expand it via executive order in 2015, a Texas judge blocked the expansion with a nationwide injunction. When Trump tried to end DACA, judges in California, New York and Washington, D.C. blocked that move. The program, and the legal challenges to it, continued under President Joe Biden. Now, the second Trump administration faces continued legal challenges over the constitutionality of the DACA program.

More recently, judges have used nationwide injunctions to block several Trump policies. Three courts stopped the president’s attempt to deny citizenship to babies born to mothers who lack legal permanent residency in the United States – the cases that led the Supreme Court to limit the reach of injunctions. Judges have also temporarily blocked Trump’s efforts to ban transgender people from serving in the military and to freeze some federal funding for a variety of programs.

Nationwide injunctions have also blocked congressional legislation.

The Corporate Transparency Act, passed in 2021 and originally scheduled to go into effect in 2024, combats financial crimes by requiring businesses to disclose their true owners to the government. A Texas judge blocked this law in 2024 after gun stores challenged it.

In early 2025, the Supreme Court allowed the law to take effect, but the Trump administration announced it simply wouldn’t enforce it – showing how these legal battles can become political power struggles.

A ruling that Congress could change

The Supreme Court’s decision in Trump v. CASA was notably narrow in its legal reasoning. The court explicitly stated that its ruling “rests solely on the statutory authority that federal courts possess under the Judiciary Act of 1789” and that it expressed “no view on the Government’s argument that Article III forecloses universal relief.”

This distinction matters enormously. Because the court based its decision on interpreting a congressional statute rather than the Constitution itself, Congress has the power to overturn the ruling simply by passing new legislation that authorizes federal judges to issue nationwide injunctions.

The Supreme Court’s majority opinion, written by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, emphasized that universal injunctions “likely exceed the equitable authority that Congress has granted to federal courts” under the Judiciary Act of 1789. The court found these injunctions lack sufficient historical precedent in traditional equity practice.

However, the three dissenting justices strongly disagreed. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson, focused on the importance of birthright citizenship, explaining that “every court to evaluate the Order has deemed it patently unconstitutional.”

As a result, the dissent argues, “the Government instead tries its hand at a different game. It asks this Court to hold that, no matter how illegal a law or policy, courts can never simply tell the Executive to stop enforcing it against anyone.”

Legislative solutions on the table

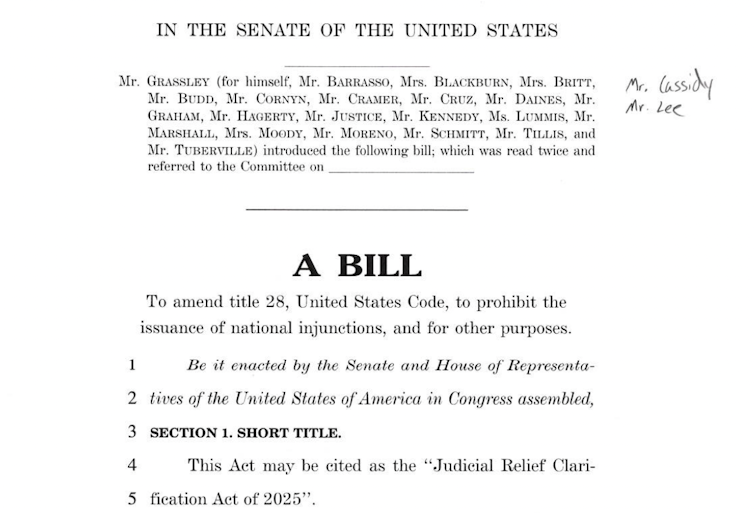

Congress was already considering legislation to limit judges’ ability to grant nationwide injunctions.

Another way to address the concerns about a single judge blocking government action would be to require a three-judge panel to hear cases involving nationwide injunctions, requiring at least two of them to agree. This is similar to how courts handled major civil rights cases in the 1950s and 1960s.

My research on this topic suggests that three judges working together would be less likely to make partisan decisions, while still being able to protect constitutional rights when necessary. Today’s technology also makes it easier for judges in different locations to work together than it was decades ago.

What comes next

With the Supreme Court limiting judges’ ability to issue nationwide injunctions based on an old statute, the ball is now in Congress’ court. Lawmakers could choose to restore this judicial power with new legislation, further restrict it, or leave the current limitations in place.

Until Congress acts, the legal landscape has fundamentally shifted.

Future challenges to presidential actions may require either cumbersome class action lawsuits or a patchwork of individual cases – potentially leaving many Americans without immediate protection from policies that courts determine violate the Constitution. But unlike a constitutional ruling, this outcome isn’t permanent: Congress holds the key to change it.

This is an updated and expanded version of a story originally published on April 3, 2025.

Cassandra Burke Robertson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

When GPS lies at sea: How electronic warfare is threatening ships and their crews

In addition to watching out for missile and drone attacks, mariners in conflict zones need to be on…

Iran’s ruling structure explained

Although the supreme leader assumes the majority of power, Iran’s regime consists of a network of…

‘Hamnet’ is making audiences break down in tears – and upending beliefs about male grief

The Oscar-nominated film about Shakespeare’s son explores how men and women mourn differently –…