Along with the ideals it expresses, the Declaration of Independence mourns for something people lost

For all the festivities around July 4, the nation’s founding document, the Declaration of Independence, actually depicts a wounded, fearful society, teetering on the brink of disaster. Sound familiar?

Right around the Fourth of July, Americans pay renewed attention to the country’s crucial founding document, the Declaration of Independence. Whether Republican or Democrat or independent, some will say – with reverence – that adherence to the values expressed in the declaration is what makes them American.

President Barack Obama, in his second inaugural address, gave voice to this very conviction.

“What binds this nation together,” he stated, “is not the colors of our skin or the tenets of our faith or the origins of our names.” What truly makes Americans American, he resolved, “is our allegiance to an idea, articulated in a declaration made more than two centuries ago.”

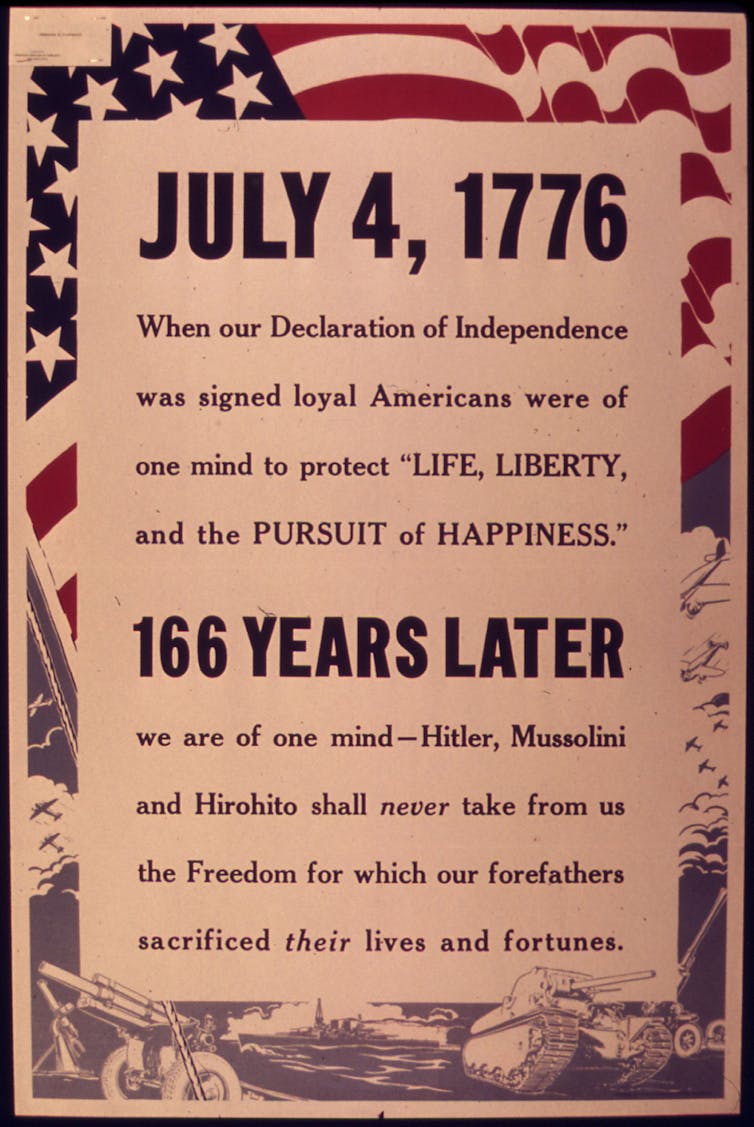

The declaration still stands today as a manifesto. There are its lofty, “self-evident” principles, of course: that “all men are created equal” and that they are “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights” such as “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

But I’m a historian of the early republic, and I wish to remind you that the declaration doesn’t just go all pie in the sky. And it’s more than an academic paper waxing on and on about the fashionable philosophical doctrines of the 18th century – freedom and equality – or the coolest philosopher ever, John Locke.

The declaration provides a realistic depiction of a wounded society, one shivering with fears and teetering on the brink of disaster.

Repeated injuries and usurpations

On June 11, 1776, the Continental Congress asked five of its members to prepare a text that would notify the British king and his Parliament of America’s firm intention to get a divorce.

The drafting committee comprised Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and a man who had a stellar reputation as a gifted writer, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia.

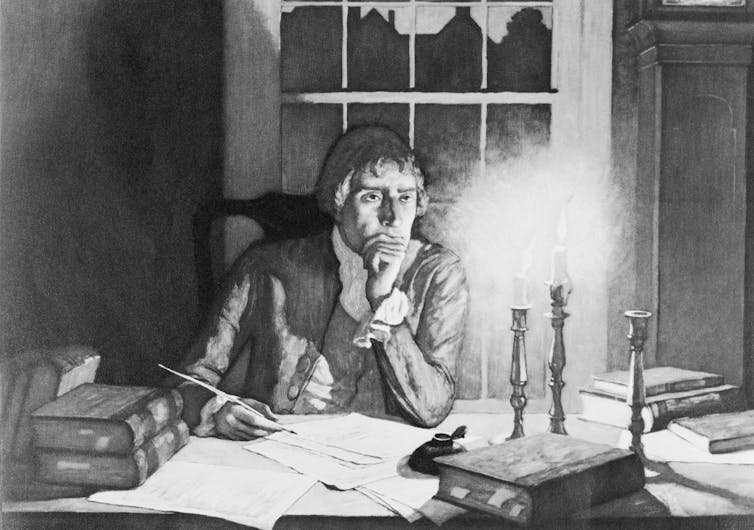

Jefferson didn’t waste time. He locked himself up in a rented room near the State House in Philadelphia, and within a couple of days he was ready to submit a draft to his four teammates for revision.

The committee was smitten by the clarity and effectiveness of the document. Other than suggesting a few corrections, Jefferson’s colleagues were elated by the text.

The Continental Congress promptly received the document, discussed it, made a handful of alterations, and in the late morning of July 4, 1776, adopted it.

Late that night, Philadelphia printer John Dunlap was given the historic task of issuing the first copies of the final Declaration of Independence.

In retrospect, all of this may sound like a tale of fearless heroes eager to break the chains of oppression and single-handedly affirm their boundless love of freedom.

However, when Thomas Jefferson took the pen in his hand, he didn’t think of himself as a hero. Rather, looking ahead at the immediate future and the drama that would inexorably unfold, he felt overwhelmed. A war, pitting brethren against brethren, the Colonists against their mother country, had already started.

The situation was tense and painful, because 18th-century Americans didn’t quite see themselves as Americans. They trusted they were active members of a powerful, expanding British Empire.

What had begun as yet another crisis over Parliament’s right to tax its overseas possessions had quickly transformed into a turning point over whether the Colonies should become independent.

As a consequence, readers of the declaration cannot escape the impression that this document carries a sense of reluctance, betrayal, fear and even sadness.

We Colonists thought we were free, the logic of the declaration goes, but now we are waking up to the dismal realization that the king and the Parliament treat us like their personal slaves.

Jefferson’s words appear to longingly express how wonderful it would be for “one people” not to be put in the condition to “dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another.” How desirable it would have been if a way to renew “the ties of our common kindred” could be found.

Unfortunately, what Jefferson calls “repeated injuries and usurpations” have created enemies out of a common ancestry, thus stifling the “voice of justice and of consanguinity.”

How not to grieve at these “injuries”? The king is guilty for “abolishing our most valuable Laws”; he has “excited domestic insurrections amongst us”; he has sent “Officers to harass our people”; he has obstructed “the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners”; and he has “made Judges dependent on his Will alone.”

Americans didn’t seek a revolution, the declaration concludes, but Colonists must accept “the necessity” of a separation: “Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government.”

‘Forget our former love for them’

Americans today may believe that the Declaration of Independence belongs to them – which it does. The declaration is an American document.

But to an even larger extent, it belongs to Thomas Jefferson. It’s a Jeffersonian document.

One of the most consequential American philosophers, the author of the declaration poured into the text his theories of society and of human nature.

For him, human beings should not live as isolated atoms in constant competition against each other. Jefferson was a communitarian, which means that he believed that the very happiness voiced in the declaration could occur only when individuals regard themselves as functional parts of a larger whole made of other human beings.

The declaration was built upon the tenet that, as Jefferson would explain many years later, “Nature hath implanted in our breasts a love of others, a sense of duty to them, a moral instinct in short, which prompts us irresistibly to feel and to succour their distresses.”

As a moral philosopher, Jefferson wasn’t perfect, obviously – and his views on race and slavery prove that. But the declaration puts forth the argument that the British king and the Parliament are also to blame for having transformed a united people, a people who used to love each other, into a mass of foreigners suspicious of each other.

In Jefferson’s account, this king has carried out the supreme betrayal – like tyrannical powers often do. He has stabbed the Americans as well as the British. He has split them into antagonistic parties. And we Americans, as Jefferson wrote in a telling passage of the declaration that didn’t survive revisions, “must endeavor to forget our former love for them.”

The American nation was born of the traumatic experience of an amputation. It’s a residual half of a former whole that one way or another managed to learn to become a whole again.

But after 250 years, America appears once more a people who seem to have lost what binds them together. Those “political bands which have connected them with another” are being tested; “the ties of … common kindred” are frayed.

Such words describe a time, centuries ago, of great uncertainty, fear and sadness. It seems America has arrived yet again at such a time.

Maurizio Valsania does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

As the Oscars approach, Hollywood grapples with AI’s growing influence on filmmaking

AI tools can now generate movie scenes, resurrect lost footage and replace entry-level jobs – forcing…

How sewage treatment plants could handle food waste, sparing landfills and the climate

Rather than generating climate-warming emissions and wasting nutrients and energy, food waste can become…

‘Hamnet’ is making audiences break down in tears – and upending beliefs about male grief

The Oscar-nominated film about Shakespeare’s son explores how men and women mourn differently –…