Detroit voters have an opportunity to pick a mayor who will ease zoning, improve transit and protect

Candidates to be the next mayor of Detroit want to help build back neighborhoods. A real estate policy expert has some ideas.

Five of the nine candidates in Detroit’s mayoral contest debated on May 29, 2025, during the annual Mackinac Policy Conference.

When asked about outgoing Mayor Mike Duggan’s 11-year tenure, many of the candidates praised him for skillfully steering Detroit through bankruptcy and attracting new business investment.

But the candidates also saw an opportunity to do more.

“Without a doubt, we have to ensure that more investment comes back into our neighborhoods and that we’re activating our commercial corridors,” the race’s front-runner, Detroit City Council President Mary Sheffield, said.

Helping Detroit residents improve their neighborhoods will be an important task for the city’s next mayor. I do not live in Detroit, but my family lived there for generations before my grandparents joined the white flight from the city in the 1970s. And my research on housing, infrastructure and land use law offers some ideas for how the next mayor could encourage investment while at the same time improving social equity.

Duggan’s legacy

By most accounts, the Motor City under Duggan has been an urban revitalization success story.

Once the nation’s murder capital, its crime rate has fallen dramatically.

And after experiencing the largest-ever municipal bankruptcy, the city boasts an investment-grade credit rating. For the past two years, the city has gained population after decades of losses. But many of the city’s neighborhoods, from Brightmoor to Jefferson-Chalmers, have not experienced the same economic surge as its booming downtown.

In the city center, offices are being converted to apartments, Michigan’s second-tallest building is rising along with other new developments, and the city has hosted major national events such as the NFL draft. Yet some of Detroit’s outlying areas still suffer from disinvestment and abandonment, poor infrastructure, underperforming schools and crime.

Many Detroiters are concerned the city’s boom might displace longtime residents if it causes housing prices to increase dramatically or removes affordable homes from the market.

Detroit’s voters will narrow the field to two candidates on Aug. 5. To help voters evaluate the candidates’ positions between now and then, here are some research-backed ideas for improving life in the city.

Make it easy to build

Detroit’s next mayor can make it easier to build new homes and businesses in the city’s neighborhoods.

Repopulating neighborhoods reduces visual blight, brings life to vacant areas and improves the city’s fiscal health by bringing in new tax revenue. Population growth also supports neighborhood businesses that create jobs and serve the community. And it will mitigate the city’s recent, steep growth in housing prices by adding new supply to the market.

Easing zoning and building rules is a good place to start. U.S. cities such as Minneapolis and Portland have recently reformed zoning laws to simplify housing construction. They’ve also modified single-family zoning citywide to allow multiplexes and accessory dwelling units. Those interventions have resulted in a small increase in new housing. Even more construction has taken place in cities such as Denver that have allowed higher-density development along major corridors – projects that can be more easily scaled and financed due to their larger size and attractiveness to investors.

To date, Detroit has not adopted any of these reforms.

Another way to spur building is to offer developers a predictable approval process. Even if cities maintain building height restrictions, setbacks and design requirements – things Detroit has maintained – predictable procedures reduce development costs and assure investors that projects can be completed on time. For example, cities can shorten the time it takes to review a project. They can also avoid city council or planning commission public hearings with subjective review criteria, which Detroit currently allows under its zoning laws.

Detroit’s initial efforts to update its zoning in 2018 stalled. Yet the city has an opportunity to become the nation’s easiest place to build, and doing so will ensure that it remains affordable while attracting investment.

Improve transit service

Detroit’s next mayor can aid its neighborhoods by improving transit service.

Without a regional transit system, southeast Michigan remains heavily car-dependent. Yet a 2017 study showed less than half of low-income Detroiters own cars. And of those who don’t own a car, 43% missed work, an appointment or something else due to a lack of transportation. Although this study is several years old, these statistics likely haven’t changed much due to rising costs of housing and car ownership.

Today, nearly one-third of Detroiters live in poverty – meaning, for a family of four, they earn less than US$32,000 per year – yet the national average annual cost of car ownership exceeds $12,000. Giving lower-income Detroiters a low-cost, reliable means to get to work would benefit the city’s neighborhoods, residents and businesses.

Expanding transit service has other benefits, too. Transit reduces traffic, encourages the healthy habit of walking to and from stops and improves air quality. Transit investments also increase land values around stations and brings new businesses to these neighborhoods. In addition to serving the needs of working Detroiters, more frequent and reliable bus service would increase neighborhood property values, according to research.

Make property taxes fairer

Since the city’s emergence from bankruptcy 11 years ago, housing wealth in Detroit has grown by $4.6 billion.

Although a rise in land values signals investor confidence in the city and benefits its homeowners, high prices limit Detroiters’ ability to afford housing, the wealth is not shared with everyone, and there is heightened risk of displacing low-income residents.

And, as candidates frequently mentioned during the debate, after more than 40 years of tax increases to make up for sliding property values, the city has one of the highest effective property tax rates in Michigan, over 2.8%, making housing even less affordable. Nevertheless, Detroit routinely abates taxes for major commercial developments such as Hudson’s Detroit and several downtown hotels, which some residents view as unfair.

Detroit’s next mayor has an opportunity to reduce the property tax burden for residents and businesses, improve the system’s fairness, and use increasing land prices and new development for public benefit.

Duggan proposed a land-value tax to replace the city’s property tax in 2023. Unlike property taxes, land-value taxes place a levy on the value of land, not structures on the land. These taxes create an incentive for owners to develop their properties for productive use rather than speculate on underutilized land.

In a city like Detroit, with thousands of vacant properties, a land-value tax would encourage development by limiting the benefits of long-term land speculation. For lower-income homeowners and renters, the city could avoid displacement through exemptions and other mechanisms.

Duggan’s proposal failed in the Michigan Legislature, which needs to approve changes to the property tax. But Detroit’s next mayor could revive this push.

The next mayor could also press the Legislature for other tools, such as the authority to levy development impact fees to build parks and schools or provide social services in neighborhoods affected by new development.

Michigan law allows the formation of special assessment districts, business improvement zones and other special taxing entities to provide public infrastructure. Expanding these tools may allow Detroit to leverage rising property values to provide public benefits such as streets or parks.

Importantly, the city can gain better public services and infrastructure while encouraging development. Tools such as the city’s community benefits ordinance, which requires developers of large projects to negotiate with neighbors for services and amenities, look good on paper but can delay projects or mistake individuals’ interests for community needs. Similarly, affordable housing mandates often lead to counterproductive results such as discouraging new development or raising costs on market-rate housing.

Brian J. Connolly does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Trump administration axed nutrition education program that saved more money than it cost, even as go

Every dollar spent on community health education through SNAP-ED saved an estimated $10.64 in Medicaid…

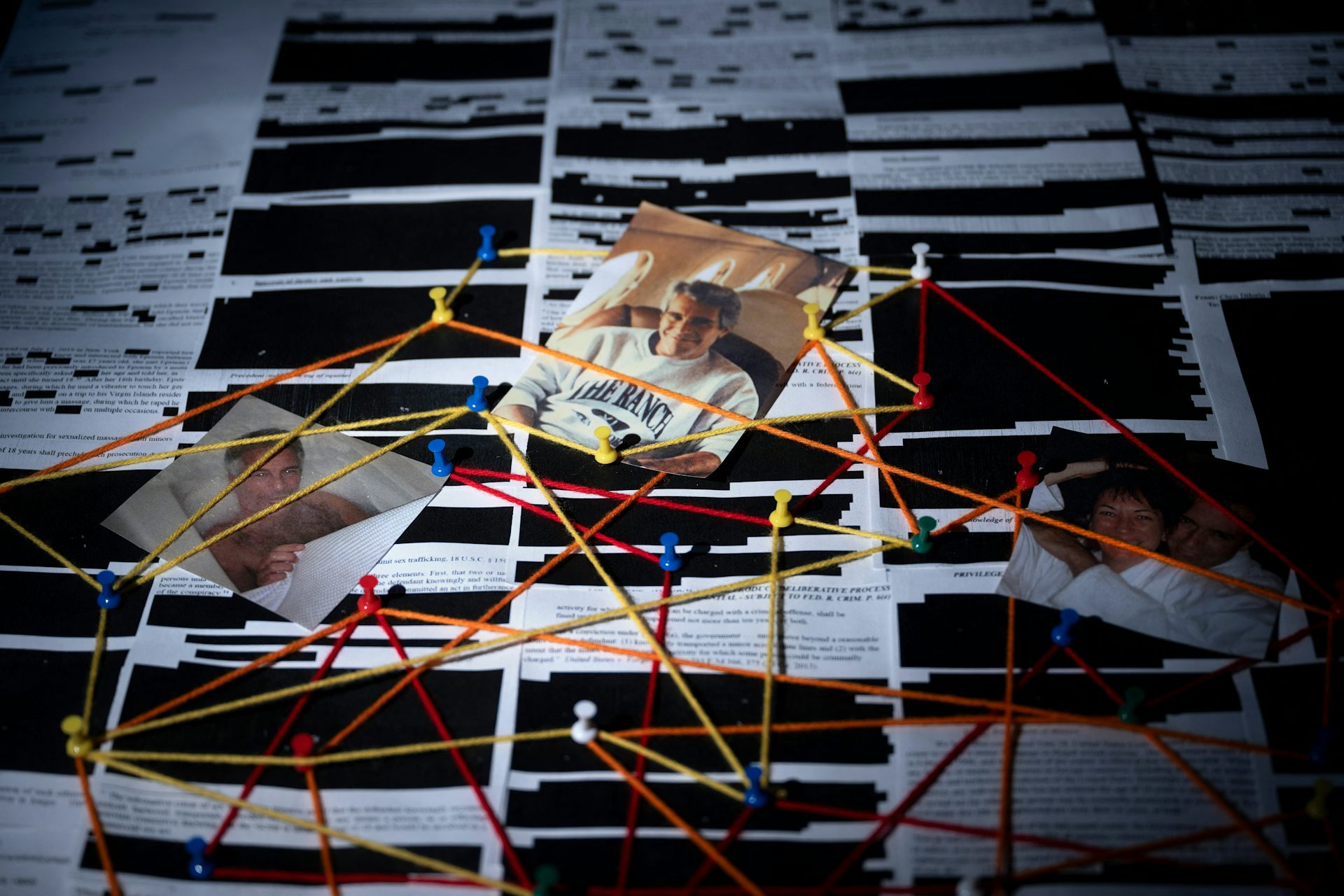

Individual donors provide only a small slice of university research funding – but Jeffrey Epstein’s

A small portion of university research funding comes from individual donors. Most universities have…

Last nuclear weapons limits expired – pushing world toward new arms race

The expiration of the New START treaty has the US and Russia poised to increase the number of their…