Why some towns lose local news − and others don’t

Since 2005, the US has lost over one-third of its local newspapers. A scholar found out why some communities can keep their papers − while others can’t.

Why did your hometown newspaper vanish while the next town over kept theirs?

This isn’t bad luck − it’s a systemic pattern. Since 2005, the United States has lost over one-third of its local newspapers, creating “news deserts” where corruption is more likely to spread and communities may become politically polarized.

My research, published in Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, analyzes the factors behind the decline of local newspapers between 2004 and 2018. It identifies five key drivers − ranging from racial disparity to market forces − that determine which towns lose their papers and which ones beat the odds.

1. Newspapers follow the money, not community needs

You might expect news media to gravitate toward areas where their work is needed most − communities experiencing population growth or facing systemic challenges. But in reality, newspapers, like any business, tend to thrive where the financial resources are greatest.

My analyses suggest that local newspapers survive where affluent subscribers and deep-pocketed advertisers cluster. That means wealthy white suburbs keep their watchdogs, while low-income and diverse communities lose theirs.

When police brutality spikes, when welfare offices deny claims, when local officials divert funds − these are the moments when communities need their journalists the most.

Poor and racially diverse communities often face the harshest policing and interact more with street-level bureaucrats than wealthier citizens. That makes them more vulnerable to government corruption and misconduct. Yet, these same communities are the first to lose their newspapers, because there are no luxury real estate agencies buying ads, and few residents can afford the monthly subscriptions.

Without journalistic scrutiny, scholars find that mismanagement flourishes, corruption costs balloon, and the communities most vulnerable to abuse receive the least accountability. This is how news deserts exacerbate inequality.

2. Newspapers don’t adequately serve diverse communities

Picture this: A newsroom sends its reporters, most of whom are white, to a Black neighborhood − but only after reports of gunshots or building fires. Residents, still in shock, don’t want to talk. So journalists call the same three community leaders they always quote, run the tragic story and disappear until the next crisis. This approach, often referred to as “parachute journalism,” results in shallow coverage that paints the community in a negative light while overlooking its complexities.

Year after year, the pattern repeats. The only time residents see their neighborhood in the paper is when something terrible happens. No feature story of the family-owned restaurant celebrating its 20-year anniversary, no reporter at the town hall when the new police chief gets grilled about stop-and-frisk − just the constant drumbeat of crime and crisis.

Is it any wonder racially diverse communities stop trusting and paying for that paper? Not when many working-class families of color can barely afford to add a newspaper subscription to their bills.

Diverse neighborhoods get hit twice. First, their local papers inadequately represent them. Then, when people understandably turn away, subscriptions drop, advertisers pull back and the outlets shut down, leaving whole communities without a voice.

Only in recent years have more media outlets begun to make a concerted effort to engage with and reflect the communities they serve. However, such efforts are often led by newer media organizations with fresh ideologies, while many long-standing media outlets remain stuck in traditional reporting practices, as illustrated in Jacob Nelson’s “Imagined Audiences.” Although my analyses of local newspaper decline from 2004 to 2018 paints a frustrating picture, the emerging trend of community-oriented journalism holds promise for positive changes in diverse communities.

3. Population growth doesn’t always save newspapers

It’s easy to assume that more people = more readers = healthier news organizations. But my research tells a different story: Counties with larger population growth actually saw greater declines in local newspapers.

The catch lies in who is moving in: Population growth saves papers only when it comes with wealth. Affluent newcomers bring subscriptions and advertisers’ attention. But growth driven by high birth rates, typically seen in less developed areas with more racial and ethnic minorities, doesn’t translate to revenue. In short, growth alone isn’t enough − it’s the type of growth, and the economic power behind it, that matters.

This highlights the fragility of market-dependent journalism. The news gap experienced by fast-growing communities may persist where local journalism depends primarily on traditional advertising and subscription revenues rather than diversified revenue sources such as grants and philanthropic donations. The latter, which often focus on community needs rather than profit potential, are more likely to help sustain journalism in areas with significant population growth.

4. Neighbors’ newspapers can save yours

You’d think that competition between newspapers would be a cutthroat affair. But in an era of decline, my analyses reveal a counterintuitive truth: Your town’s paper actually has better odds when nearby communities keep theirs.

Rather than competing, neighboring papers often become allies, sharing breaking news, splitting investigative costs and attracting advertisers who want regional reach. While this collaboration can sometimes cause papers to lose their local identity, having some local journalism is still better than none. It ensures some level of accountability, even if the news isn’t as focused on each town’s unique needs.

Resilient local journalism clusters together. When one paper invests in original reporting, its neighbors often benefit too. When regional businesses support multiple outlets, the entire news ecosystem becomes more sustainable.

5. Left or right? Local papers die either way

In this highly polarized era, it turns out that there’s no significant link between a county’s partisan makeup and its ability to keep newspapers.

Urban hubs such as Chicago keep robust media thanks to dense populations and corporate advertisers, not because they vote for Democrats. Meanwhile, newspapers in conservative rural areas can survive by cultivating loyal readerships within their communities.

In contrast, communities with lower income and a diverse population lose outlets no matter whether they are red, blue or purple.

Partisan battles might dominate national headlines, but local journalism’s survival hinges on practical factors such as money and market size. Saving local news isn’t a left vs. right debate − it’s a community issue that requires nonpartisan solutions.

Abby Youran Qin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

As war in Ukraine enters a 5th year, will the ‘Putin consensus’ among Russians hold?

Polling in Russia suggests strong support for President Vladimir Putin. Yet below the surface, popular…

Trump administration axed nutrition education program that saved more money than it cost, even as go

Every dollar spent on community health education through SNAP-ED saved an estimated $10.64 in Medicaid…

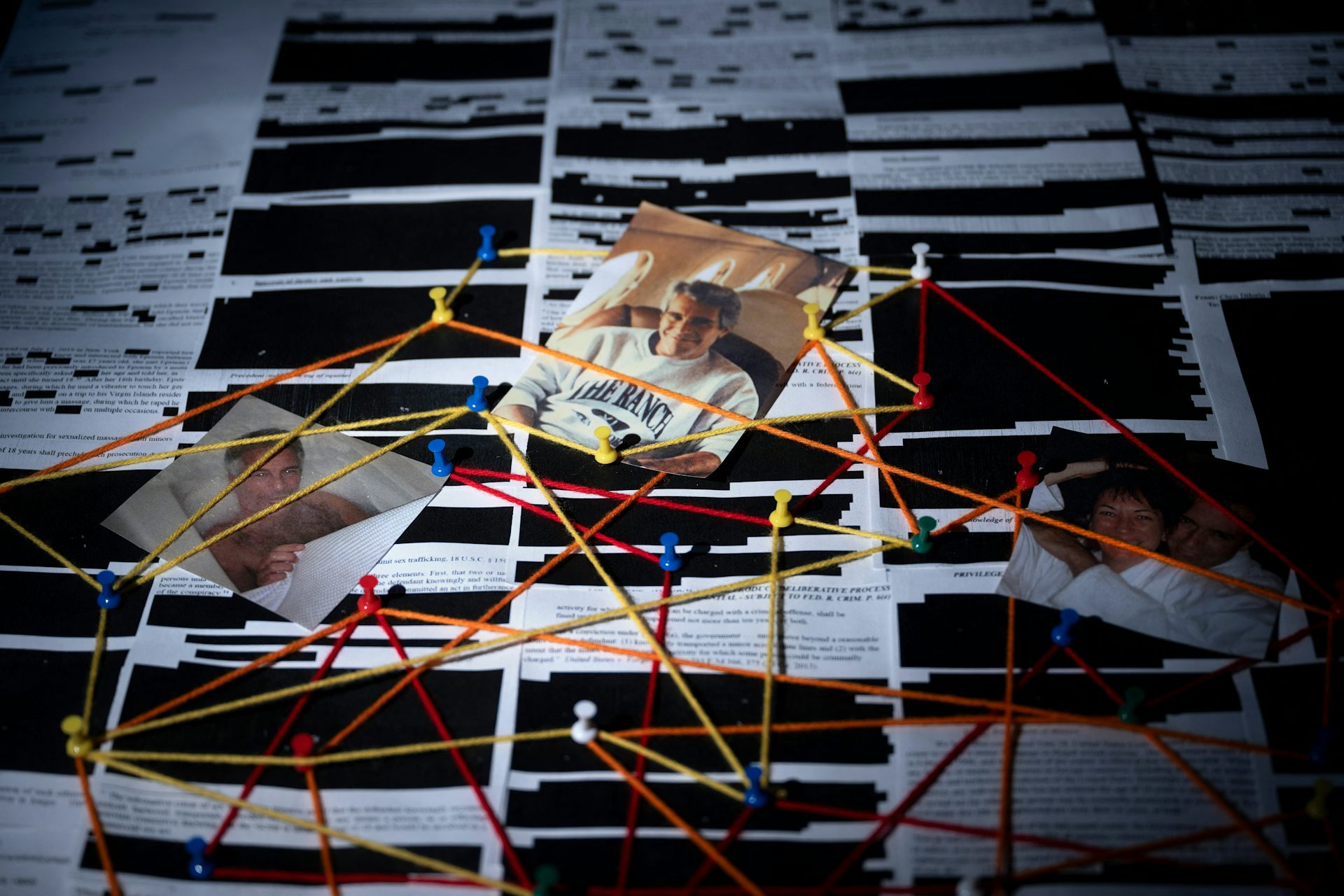

Individual donors provide only a small slice of university research funding – but Jeffrey Epstein’s

A small portion of university research funding comes from individual donors. Most universities have…