Beatings, overcrowding and food deprivation: US deportees face distressing human rights conditions i

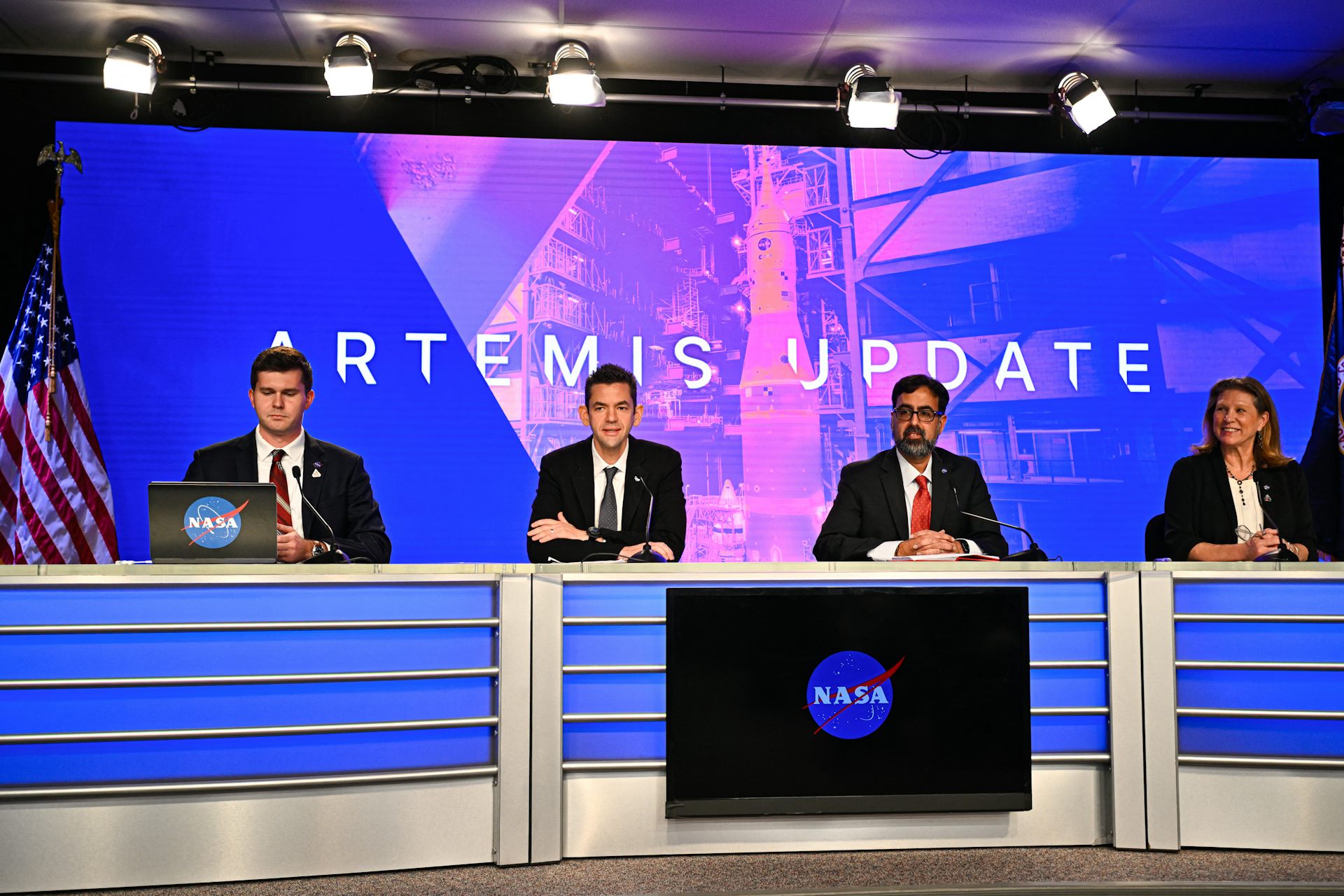

El Salvador has the highest prison population rate in the world. The US administration intends to increase the number of people behind bars there.

El Salvador President Nayib Bukele framed his offer to house “dangerous American criminals” and “criminals from any country” as a win-win for all.

The fee for transferring detainees to a newly built Salvadoran mega-prison “would be relatively low” for the U.S. but enough to make El Salvador’s “entire prison system sustainable,” Bukele wrote in a post on the social media platform X dated Feb. 3, 2025.

What was left unsaid is that the individuals would be knowingly placed into a prison system in which a range of sources have reported widespread human rights abuses at the hands of state forces.

A first transfer of U.S. deportees from Venezuela has now arrived into that system. On March 16, the U.S. government flew around 250 deportees to El Salvador despite a judge’s order temporarily blocking the move. Bukele later posted a video online showing the deportees arriving in El Salvador with their hands and feet shackled and forcibly bent over by armed guards.

As experts who have researched human rights and prison conditions in El Salvador, we have documented an alarming democratic decline amid Bukele’s attempts to conceal ongoing violence both in prisons and throughout the country.

We have also heard firsthand of the human rights abuses that deportees and Salvadorans alike say they have suffered while incarcerated in El Salvador, and we have worked on hundreds of asylum cases as expert witnesses, testifying in U.S. immigration court about the nature and scope of human rights abuses in the country. We are deeply concerned both over the conditions into which deportees are arriving and as to what the U.S. administration’s decision signals about its commitments to international human rights standards.

Eroding democratic norms

Bukele has led El Salvador since 2019, winning the presidency by vowing to crack down on the crime and corruption that had plagued the nation. But he has also circumvented democratic norms – for example, by rewriting the constitution so that he could be reelected in 2024.

For the past three years, Bukele has governed with few checks and balances under a self-imposed “state of exception.” This emergency status has allowed Bukele to suspend many rights as he wages what he calls a “war on gangs.”

The crackdown manifests in mass arbitrary arrests of anyone who fits stereotypical demographic characteristics of gang members, like having tattoos, a prior criminal record or even just “looking nervous.”

As a result of the ongoing mass arrests, El Salvador now has the highest incarceration rate in the world. The proportion of its population that El Salvador incarcerates is more than triple that of the U.S. and double that of the next nearest country, Cuba.

Safest country in Latin America?

Bukele’s tough-on-gangs persona has earned him widespread popularity at home and abroad – he has fostered an immediate friendship with the new U.S. administration in particular.

But maintaining this popularity has involved, it is widely alleged, manipulating crime statistics, attacking journalists who criticize him and denying involvement in a widely documented secret gang pact that unraveled just before the start of the state of exception.

Bukele and pro-government Salvadoran media insist that the crackdown on gangs has transformed El Salvador into the safest country in Latin America.

But on the ground, Salvadorans have described how police, military personnel and Mexican cartels have taken over the exploitative practices previously carried out by gangs like MS-13 and Barrio 18. One Salvadoran woman whose son died in prison just a few days after he was arbitrarily detained told a reporter from Al Jazeera: “One is always afraid. Before it was fear of the gangs, now it’s also the security forces who take innocent people.”

Torture as state policy

Bukele’s crackdown on gangs has come at a huge cost to human rights – and nowhere is this seen more than in El Salvador’s prison system.

Bukele has ordered a communication blackout between incarcerated people and their loved ones. This means no visits, no letters and no phone calls.

Such lack of contact makes it nearly impossible for people to determine the well-being of their incarcerated family members, many of whom are parents with young children now cared for by extended family.

Despite the blackout, scholars, international and national rights’ groups and investigative journalists have been able to build up a picture of conditions inside El Salvador’s prisons through interviews with victims and their family members, medical records and forensic analysis of cases of prison deaths. What they describe is a hellscape.

Incarcerated Salvadorans are packed into grossly overcrowded cells, beaten regularly by prison personnel and denied medicines even when they are available. Inmates are frequently subjected to punishments including food deprivation and electric shocks. Indeed, a U.S. State Department’s 2023 country report on El Salvador noted the “harsh and life-threatening prison conditions.”

The human rights organization Cristosal estimates that hundreds have died from malnutrition, blunt force trauma, strangulation and lack of lifesaving medical treatment.

Often, their bodies are buried by government workers in mass graves without notifying families.

Although El Salvador is a signatory to the United Nations’ Convention Against Torture, Amnesty International concluded after multiple missions to the country and interviews with victims and their families that there is “systemic use of torture” in Salvadoran prisons.

Likewise, a case-by-case study by Cristosal, which included forensic analysis of exhumed bodies of people who died in prison, determined in 2024 that “torture has become a state policy.”

‘At risk of irreparable harm’

What makes this all the more worrying is the scale of potential abuse.

El Salvador now houses a prison population of around 110,000 – more than three times the number of inmates before the state of exception began.

To increase the country’s capacity for ongoing mass incarceration, Bukele built and opened the Terrorism Confinement Center mega-prison in 2023. An analysis of the center using satellite footage showed that if the prison were to reach its full supposed capacity of 40,000, each prisoner would have less than 2 feet of space in their cells.

It is to this prison that deportees from the U.S. have been taken.

President Donald Trump invoked the 1798 Alien Enemies Act in transferring the detainees. The wartime act has been invoked only three times, including to justify Japanese internment during World War II.

There are serious concerns over both the process and the legality of transferring U.S. prisoners to a nation that has not protected the human rights of its detained population.

While Trump said the deportees were members of the gangs Tren de Aragua and MS-13, the incarcerated individuals did not receive a hearing to contest allegations of their gang membership, eliciting questions as to the viability of that claim.

Moreover, the agreement through which the Trump administration is seeking to moving migrants detained in the U.S. to El Salvador faces scrutiny under international law, given what is known about the country’s prison conditions.

International human rights is governed by laws that prohibit nations from transferring people into harm’s way, be it returning foreign nationals to countries where “there are substantial grounds for believing that the person would be at risk of irreparable harm,” or transferring detainees to jurisdictions in which they are at risk of being tortured or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

The efforts of human rights organizations, journalists and scholars to document prison conditions point to an unequivocal conclusion: El Salvador does not meet the terms necessary to protect the human rights of deported and incarcerated migrants.

To the contrary, the government of El Salvador has repeatedly been accused by rights groups of committing crimes against humanity, including against its prison population.

Mneesha Gellman received funding from Emerson College's Faculty Development Fund. She is the Director of the Emerson Prison Initiative.

Sarah C. Bishop has received research funding from the Fulbright Organization, The Waterhouse Family Institute for the Study of Communication and Society at Villanova University, the Robert Bosch Stiftung Foundation, and the Professional Staff Congress at the City University of New York. She serves on the board of directors of the nonprofit organization Mixteca.

Read These Next

GLP-1 drugs may fight addiction across every major substance, according to a study of 600,000 people

GLP-1 drugs are the first medication to show promise for treating addiction to a wide range of substances.

Congress once fought to limit a president’s war powers − more than 50 years later, its successors ar

At the tail end of the Vietnam War, Congress engaged in a breathtaking act of legislative assertion,…

Housing First helps people find permanent homes in Detroit − but HUD plans to divert funds to short-

Detroit’s homelessness response system could lose millions of dollars in federal funding for permanent…