Alien and Sedition Acts were reviled in their time, and John Adams was not sorry to see them go

John Adams signed the Sedition Act in an attempt to silence dissent. Some other Founding Fathers thought that muzzling the press would mean the end of the republic.

When John Adams became the second president of the United States in 1797, he inherited from George Washington a new experiment in government and a bit of a mess. The country’s two political parties – the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans – were increasingly hostile to one another, and the young nation was sinking deeper into a foreign policy crisis with its onetime ally France.

Adams’ Federalist Party wanted to fight; the Democratic-Republicans did not. As the situation with France, caused by the seizure of American merchant ships, deteriorated, Adams had to prepare his country for war.

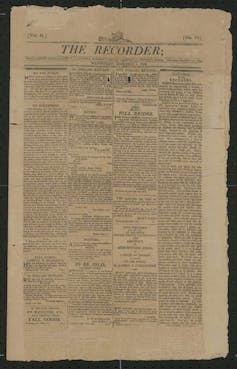

In an attempt to silence the Federalists’ political opponents, he signed the Sedition Act of 1798. The new law attempted to crack down on critical writings about government officials, and it was aimed at Democratic-Republican newspaper editors in particular.

Signing the Sedition Act was a reputation-ruining decision. This one act painted Adams as a man who put national security and his reputation above freedom of speech and the press. Yet the real story behind the Sedition Act, which I know from my work as a John Adams and American Revolution scholar, reveals a more complicated calculus.

At a time when the current presidential administration is tightening control of the media and even invoking the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 – which Adams signed into law alongside the Sedition Act – it is important to understand this first attempt to control what kind of news the American people received.

Little choice but to sign

The Sedition Act made it illegal to “write, print, utter or publish … any false, scandalous and malicious” statements, particularly those that might “stir up sedition within the United States, or to excite any unlawful combinations therein, for opposing or resisting any law of the United States.”

It was one of four laws Congress passed in 1798 in an attempt to solve a perceived threat from the French and their supporters in the U.S. The other three acts affected immigrants, increasing residency requirements for citizenship from five to 14 years and giving the president broad authority to detain or deport “aliens” deemed dangerous.

Collectively, this legislation is known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Democratic-Republicans opposed the whole package as unconstitutional, but it was the Sedition Act that tainted Adams’ reputation.

I can’t let Adams off the hook for restricting freedom of the press, even temporarily – the Sedition Act expired in 1801 – but context is important.

While drafting the Bill of Rights two decades prior, James Madison and his congressional colleagues could not agree on the exact language for the First Amendment, which guarantees the rights to free speech and a free press. Between 1791, when it was adopted, and Adams’ signing of the laws in 1798, no court case had put those rights to the test and hashed out its meaning.

In 1798, the question was: Should there be restrictions on these rights, or should the press have free rein to print whatever it wanted?

Neither Congress nor Adams knew exactly how to interpret the First Amendment. The Supreme Court would not take up freedom of speech and the press until decades later, in 1821.

Reluctant decision in a crisis

My research and that of other scholars suggest that Adams was never an advocate of the Sedition Act. He neither asked for the legislation, nor did he lobby for it.

“I regret not the repeal of the Alien or Sedition Law, which were never favorites with me,” he told his son in later life.

He never indicated why he made the poor decision to sign the law. But he was acting in a time of crisis, and I suspect he felt he had no choice. The U.S. was preparing for war. The newly built USS Constitution was ready to set sail for the Caribbean to protect American merchant ships from French privateers.

The Sedition Act wouldn’t be the last time a fearful U.S. Congress preparing for war would try to silence opposition. In 1918, during World War I, Congress passed – and President Woodrow Wilson signed – a new Sedition Act that imposed harsh penalties for speech abusing the U.S. government, the flag, the Constitution or the military.

Because the Sedition Act was used to silence critical media, historians and free press advocates tend to take a dim view of it. Scholars have described the Alien and Sedition Acts as “reprehensible,” and many quote Thomas Jefferson, who feared they could mean the end of the republic.

“I consider these laws as merely an experiment on the American mind to see how far it will bear an avowed violation of the Constitution,” wrote Jefferson, who succeeded Adams in 1801.

“If this goes down, we shall immediately see attempted another act of Congress declaring that the President shall continue in office during life [and] reserving to another occasion the transfer of succession to his heirs,” Jefferson concluded.

Judges abuse the law

Ultimately, 10 people were convicted under the law, most of them Democratic-Republican newspaper editors. They were tried by Federalist judges who made no secret of their political alliances.

Chief among them was Samuel Chase, who presided over the trial of scandalmongering journalist James T. Callender. Callender was convicted of sedition and jailed in the spring of 1800.

During this and other trials, Chase abandoned all pretense of impartiality, openly siding with federal prosecutors.

“A republican government can only be destroyed in two ways,” Chase said during the 1800 sedition trial of writer Thomas Cooper, sounding more like a prosecutor than a judge. “The introduction of luxury, or the licentiousness of the press.”

Yet Chase was George Washington’s appointee. Adams could scarcely interfere with judicial independence, which was already a well-enshrined principle by the late 18th century.

The parameters of free speech, however, were still nebulous and untested. Indeed, “seditious libel” – speech that might undermine respect for the government or public officials – had long been outlawed under the English Common Law system, which the U.S. inherited.

Unlike British laws around free speech, the Sedition Act allowed truth as a defense.

“It shall be lawful for the defendant,” the law read, “to give in evidence in his defence, the truth of the matter contained in publication.”

In other words, critical press about public officials remained permissible in the U.S., so long as it was accurate. Seen in that light, the Federalists claimed the Sedition Act actually improved upon British Common Law.

Mixed record

Ultimately, Adams saved the U.S. from what would have been a disastrous war by pursuing peace negotiations with France. The Federalists were furious that Adams, in 1799, had sent a peace mission to France without consulting his party. But he chose peace with France rather than subject the American people to another war.

By doing this, he put country above party and sacrificed personal popularity for the common good. Adams’ other achievements as president include creating the Naval Department and establishing the Library of Congress.

And he made tremendous contributions to the independence of the U.S. as a Founding Father. He served in both Continental Congresses, got loans from the Dutch for the war effort and helped to shape the framework of government for the states.

The Alien and Sedition Acts were mistakes that Adams lived to regret. Reviving any of them today would be, in my opinion, a worse one.

I am an Adams Memorial Foundation Scholar and have written an op-ed for them.

Read These Next

The nation is missing millions of voters due to lack of rights for former felons

At least 20 million Americans have served time. Most of them can’t or don’t vote, and that may distort…

What decades of research reveal about involuntary substance use treatment – and why evidence points

Many cities are considering involuntary substance use treatment as a solution to drug use among the…

Kansas revoked transgender people’s IDs overnight – researchers anticipate cascading health and soci

With invalid driver’s licenses and birth certificates, transgender people are at risk for more than…