What is Tren de Aragua? How the Venezuelan gang started − and why US policies may only make it stron

The State Department declared Tren de Aragua a terrorist organization, and news reports say its members are wreaking havoc across the country. The reality is more nuanced.

When the U.S. government deported 177 Venezuelans on Feb. 20, 2025, the Department of Homeland Security alleged that 80 of the deportees were members of the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua.

U.S. news outlets report that members have set up shop in at least 16 states and are “wreaking havoc on communities across the nation.”

According to Fox News, in February 2025 there was an “infestation” of Tren de Aragua members in an apartment building in Aurora, Colorado.

Suspected Tren de Aragua members have been arrested in Florida, Pennsylvania, New York, California, Texas and other states.

The U.S. State Department went so far as to designate Tren de Aragua a foreign terrorist organization in an effort to stop “the campaigns of violence and terror committed by international cartels and transnational organizations.”

There is little reliable information about Tren de Aragua – but no shortage of sensationalist news reports and Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids claiming to target them.

We are sociologists who have spent a combined 37 years researching gangs, crime and policing in Venezuela. Our research in Venezuela, and our colleagues’ research in other countries, suggests that incarceration and mass deportations of Venezuelans living in the U.S., whether they have ties to the group or not, will likely strengthen Tren de Aragua rather than cripple it.

Indeed, we have already seen how these strategies contributed to the expansion of street gangs in El Salvador and Honduras by creating new opportunities for members to network and become more organized.

What is Tren de Aragua?

According to investigative journalists and a handful of academic studies, Tren de Aragua was initially founded by Hector “El Niño” Guerrero and two other men in 2014. The three men were imprisoned in Tocorón prison in the state of Aragua.

By 2017, Tren de Aragua began to be known as a “megabanda,” a category the local press in Venezuela use to refer to large organized criminal groups. The term arose to highlight the size of some street gangs, which at the time was unprecedented in Venezuela.

Since its beginning, the gang has depended heavily on extortion. It also sells street drugs, but that has been a much less important source of revenue for it.

Tren de Aragua’s growth surged as a result of mass incarceration policies that began under Venezuela’s former President Hugo Chávez and expanded under current President Nicolás Maduro. Incarceration rates began to increase in 2009 and were exacerbated by police raids deployed in 2010 in marginalized neighborhoods across the country. Venezuela’s prisons became filled with young, poor men.

Crowded together in inhumane conditions, the men began to organize into prison gangs with clear hierarchies. They accumulated vast profits by charging prisoners fees for food, use of space and protection from inmate violence. They also opened and ran businesses, including a club, inside Tocorón prison.

Members of different gangs in and outside the prison also began to communicate and share information about criminal activities such as kidnapping and extortion. This strengthened social networks and expanded their illegal enterprises.

Tren de Aragua eventually took control of Tocorón prison as the government became unable to manage daily life inside its walls. It had become one of the largest and best organized gangs in Venezuela.

Criminal enterprise grows

Since 2014, an economic and humanitarian crisis has devastated Venezuela, causing many Venezuelans to migrate.

Venezuela had one of the highest displacement rates in the world between 2014 and 2018, when at least 3 million people left the country.

Tren de Aragua, still based in the Tocorón prison at that time, took advantage of this mass migration. It expanded the group’s business portfolio to include human trafficking and sexual exploitation of Venezuelan female migrants in Chile, Colombia and Peru.

It’s unclear how far beyond Venezuela Tren de Aragua has spread. While the group has certainly expanded operations into the Latin American countries mentioned above, research shows common criminals have posed as Tren de Aragua members in both Colombia and Chile.

Moreover, the arrest of alleged Tren de Aragua members for committing crimes in the U.S. and other countries does not mean that the gang has set up shop in those places. Gang members, same as non-gang members, migrate during crises. They may continue to commit crimes in new places after they arrive. However, it’s important to note that immigration in the U.S. is consistently linked with decreases – not increases – in both violent crime and property crime.

Even some local police departments have questioned the gang’s expansion into the U.S.

In Aurora, police refuted both the mayor’s and President Donald Trump’s claims about the apartment complex being taken over by the gang. And the New York Police Department recently reported that suspected Tren de Aragua members there are largely focused on snatching mobile phones and robbing department stores – hardly the crimes of a transnational criminal empire or terrorist organization.

Making matters worse

Deportations do not address the urgent situation faced by many migrants who leave their homelands in search of a better, safer future.

When governments prioritize the spectacle of deportations to deal with migration, they contribute to the expansion of even more resilient networks of criminal enterprises.

Recent history bears this out.

In El Salvador in the 1990s and early 2000s, incarceration, deportations and repressive policing policies contributed to the evolution of youth street gangs such as the Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, into transnational extortion rackets that spread across Central America.

These same policies could also contribute to the growth of Tren de Aragua within Latin America.

Prison isolates large groups of excluded and marginalized people and constrains them to brutal conditions. This enables and encourages the social networks that fuel illegal markets and criminal activity beyond the walls of prisons.

Rising xenophobia

Another harmful outcome of the policies we have discussed here is that they may fuel xenophobia toward and criminalization of Venezuelan immigrants living in the U.S.

This closes off opportunities and harms people already devastated by economic, political and humanitarian crises in their home country.

Venezuelans have responded with their characteristically incisive and biting humor.

Many have used social media to parody news outlets and political speeches, and Venezuelans regularly post memes and videos that mock the automatic association made between them and Tren de Aragua.

The satiric news site El Chigüire Bipolar posted stories titled “The United States confirms that Venezuelans are Tren de Aragua members from birth” and “ICE agents detain newborn that might be Tren de Aragua leader in the future.”

Meanwhile, recent cuts in U.S. foreign aid to countries with large Venezuelan populations, such as Colombia and Peru, will likely exacerbate the migration crisis by constraining opportunities for Venezuelans.

Future waves of migrants will be easy prey for criminal organizations like Tren de Aragua, which has turned human trafficking into a lucrative business. And with current policies of cutbacks, incarceration and repression, Tren de Aragua will likely continue to grow and fill its coffers.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Iran-US nuclear talks may fail due to both nations’ red lines – but that doesn’t make them futile

The US administration may sense that Iran is weak and ready to do a deal. But negotiations could be…

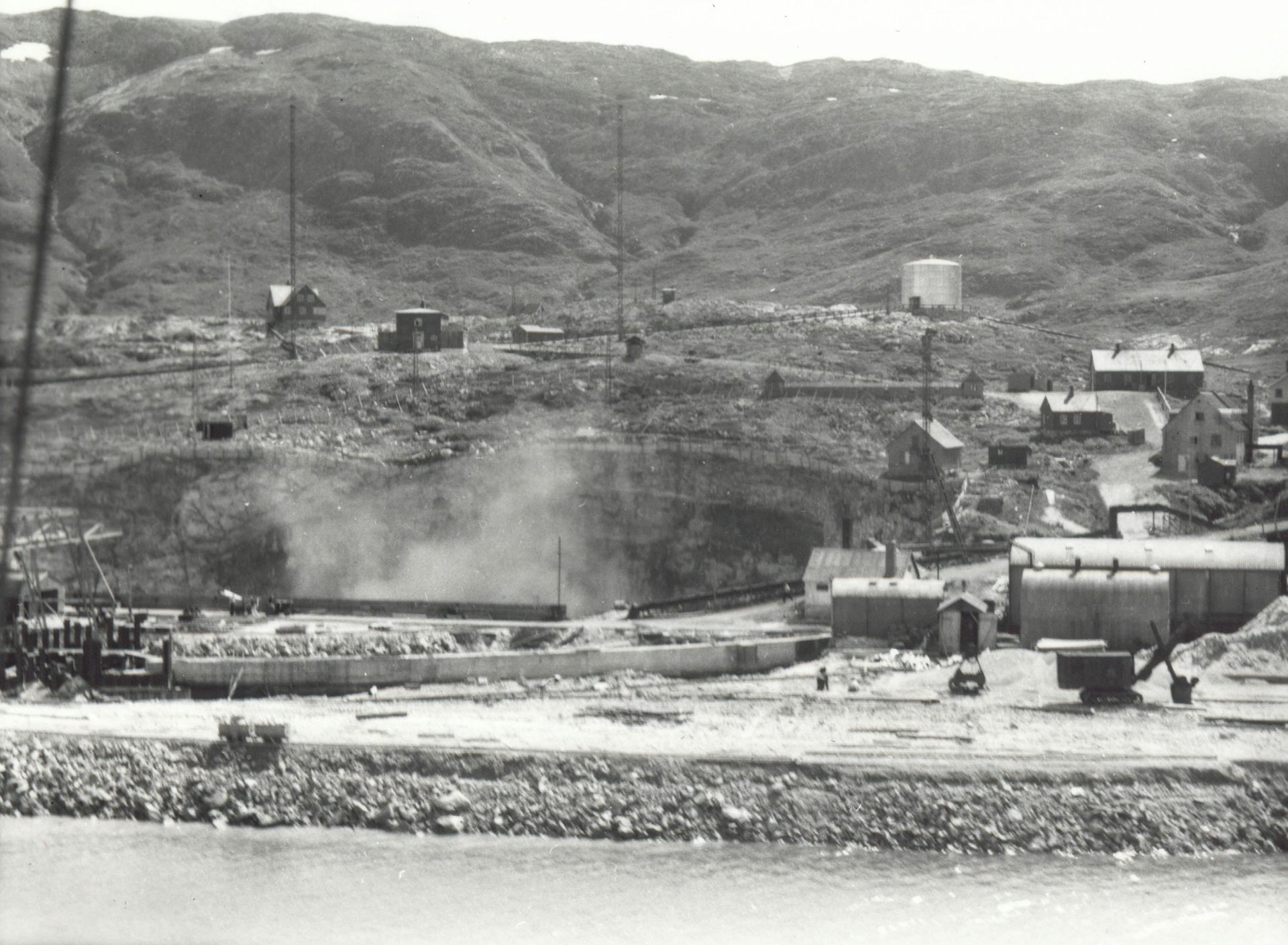

In World War II’s dog-eat-dog struggle for resources, a Greenland mine launched a new world order

Strategic resources have been central to the American-led global system for decades, as a historian…

Revisiting the story of Clementine Barnabet, a Black woman blamed for serial murders in the Jim Crow

In 1912, a young Black woman’s supposed religious beliefs were quickly blamed to make sense of a terrifying…