‘We painted our fear, hope and dreams’ − examining the art and artists of Guantánamo Bay

Using tea bags, mop strands and other camp detritus, detainees used art as a way of escape at the detention center.

When Moath al-Alwi left Guantánamo Bay for resettlement in Oman, accompanying him on his journey was a cache of artwork he created during more than two decades of detention.

Al-Alwi was detainee number “028” – an indication that he was one of the first to arrive at the U.S. military prison off Cuba after it opened in January 2002. His departure from the detention center on Jan. 6, 2025, along with 10 fellow inmates, was part of an effort to reduce the prison’s population before the end of President Joe Biden’s term.

For al-Alwi, it meant freedom not only for himself, but also for his artwork. While not all detainees shared his passion, creating art was not an uncommon pursuit inside Guantánamo – indeed it has been a feature, formally and informally, of the detention center since its opening more than 20 years ago.

As editors of the recently published book “The Guantánamo Artwork and Testimony of Moath al-Alwi: Deaf Walls Speak,” we found that art-making in Guantánamo was more than self-expression; it became a testament to detainees’ emotions and experiences and influenced relationships inside the detention center. Examining the art offers unique ways of understanding conditions inside the facility.

Art from tea bags and toilet paper

Detained without charge or trial for 23 years, al-Alwi was first cleared for release in December 2021. Due to unstable conditions in his home country of Yemen, however, his transfer was subject to finding another country for resettlement. Scheduled for release in early October 2023, he and 10 other Yemeni detainees were further delayed when the Biden administration canceled the flight due to concerns over the political climate after the Oct. 7 attacks in Israel.

During his detention, al-Alwi suffered abuse and ill treatment, including forced feedings. Making art was a way for him, and others, to survive and assert their humanity, he said. Along with fellow former detainees Sabri al-Qurashi, Ahmed Rabbani, Muhammad Ansi and Khalid Qasim, among others, al-Alwi became an accomplished artist while being held. His work was featured in several art shows and in a New York Times opinion documentary short

During the detention center’s early years, these men used whatever materials were at hand to create artwork – the edge of a tea bag to write on toilet paper, an apple stem to imprint floral and geometric patterns and poems onto Styrofoam cups, which the authorities would destroy after each meal.

In 2010, the Obama administration began offering art classes at Guantánamo in an attempt to show the world they were treating prisoners humanely and helping them occupy their time.

However, those attending were given only rudimentary supplies. And they were subjected to invasive body searches to and from class and initially shackled to the floor, with one hand chained to the table, throughout each session. Furthermore, the subject matter for their art was restricted – detainees were forbidden from representing certain aspects of their detention, and all artwork was subject to approval and risked being destroyed.

Despite this, many detainees participated in the classes for camaraderie and the opportunity to engage in some form of creative expression.

A window to freedom

Making art served many purposes. Mansoor Adayfi, a former Guantánamo Bay detainee and author of “Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantanamo,” wrote in his contribution to the book on al-Alwi that initially, “we painted what we missed: the beautiful blue sky, the sea, stars. We painted our fear, hope and dreams.”

Those who have been transferred from Guantánamo describe the art as a way to express their appreciation for culture, the natural world and their families while imprisoned by a regime that consistently characterized them as violent and inhuman.

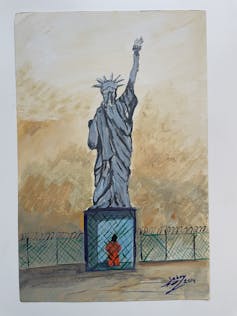

The Statue of Liberty became a frequent motif Guantánamo artists deployed to communicate the betrayal of U.S. laws and ideals. Often, Lady Liberty was depicted in distress – drowning, shackled or hooded. For Sabri al-Qurashi, the symbol of freedom under duress represented his own condition when he painted it. “I am in prison, not free, and without any rights,” he told us.

Other times, the artwork responded directly to the men’s day-to-day conditions of confinement.

One of al-Alwi’s early pieces was a model of a three-dimensional window. Approximately 40 x 55 inches, the window was filled in with images carefully torn from nature and travel magazines, and layered to create depth, so that it appeared to look out on an island with a house with palm and coconut trees made from twisted pieces of rope and soap.

Al-Alwi was initially allowed to keep it in his windowless cell, and fellow detainees and guards would visit to “look out” the window.

But, as far as we know, it was eventually lost or destroyed in a prison raid.

Art as representation and respite

In another example of how artwork can be an expression of what former detainees call their “brotherhood,” Khalid Qasim, who was imprisoned at the age of 23 and held for more than two decades before being transferred alongside al-Alwi, mixed coffee grounds and coarse sand to create a series of nine textured, evocative paintings to memorialize each of the nine men who died while held at Guantánamo.

Especially in periods when camp rules allowed detainees to create artwork in their cells, the artists’ use of prison detritus and found objects made the artwork more than simply a depiction of what the men lacked, desired or imagined. Artwork helped create an alternative forum for the men’s experiences, especially for those artists who, along with the vast majority of Guantánamo’s 779 detainees, never faced charge or trial.

The pieces served as symbols and metaphors of the detainees’ experiences. For example, al-Alwi describes his 2015 large model ship, The Ark, as fighting against the waves of an imagined, threatening sea. In creating it, he wrote, “I felt I was rescuing myself.”

Constructed out of the materials of his imprisonment, the work also points to the conditions of his daily life in Guantánamo. Made from the strands of mops, unraveled prayer cap and T-shirt threads, bottle caps, bits of sponges and cardboard from meal packaging, al-Alwi’s ships – he went on to create at least seven – reveal both his artistic ingenuity and his circumstances.

Guantánamo artists talk about the artwork as being imprisoned like them and subjected to the same restrictions and seemingly arbitrary processes of approval or disappearance.

The transfer to Oman of al-Alwi and his artwork releases both from those processes. It also creates an opportunity to inform the public about what Guantánamo meant to those who were held there, and to the 15 men who remain.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Grammys’ AI rules aim to keep music human, but large gray area leaves questions about authenticity a

AI is already in much of the music you hear. It can be as mundane as a production tool or as deceptive…

Trump’s Greenland threats reveals no-win dilemma at the heart of European security strategy

European publics and more government leaders are questioning the value of the alliance with the United…

US military action in Iran risks igniting a regional and global nuclear cascade

The Trump administration has called on Iran to permanently end its nuclear program. But threats of force…