What does the US attorney general actually do? A law professor explains

The combined political and legal roles and responsibilities of the US attorney general can create conflicts. Some attorneys general yielded to political pressure from the president – many did not.

Shortly after former Florida Rep. Matt Gaetz withdrew from consideration to serve as U.S. attorney general, President-elect Donald Trump announced he would nominate Pam Bondi for the position. A former Florida attorney general, Bondi also worked for Trump as a defense lawyer during the first of his two impeachment trials.

While much recent attention has focused on who the next attorney general might be, there has been less attention on what the attorney general actually does.

The attorney general is the lawyer appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate to lead the Department of Justice, known as the DOJ. Because the attorney general’s expansive responsibilities place the office at the forefront of both politics and the law, the position is one of the most important in the federal executive branch.

File lawsuits, give advice

Congress created the position of attorney general in 1789 so the national government had a designated lawyer to conduct federal lawsuits for crimes against the United States such as counterfeiting, piracy or treason, and to give legal advice to the president and cabinet officials, such as the secretary of the Treasury.

Initially, the attorney general served part time. Indeed, for the first few decades of U.S. history, most attorneys general maintained private law practices and even lived away from the capital. But as the federal government began to do more, the role of the attorney general grew and became a full-time job.

Today’s attorney general largely performs the same jobs as the first one, Edmund Jennings Randolph, did.

The attorney general represents the United States in all legal matters. In doing so, the attorney general supervises federal prosecutions by the 93 U.S. attorneys who live and work across the United States to enforce federal laws. The attorney general also supervises almost all legal actions involving federal agencies – from the Department of Homeland Security and the Environmental Protection Agency to the Social Security Administration.

For example, in the past few months, DOJ lawyers supervised by the attorney general have successfully prosecuted a man for conspiring to send to China trade secrets belonging to a leading electric vehicle company; worked with the city of Baltimore to adopt police reforms after DOJ opened a comprehensive investigation into the 2015 death of Freddie Gray; and found that Arizona’s Department of Child Safety discriminates against parents and children with disabilities.

Additionally, the attorney general gives legal advice to the president and heads of the cabinet departments. This includes providing recommendations to the president on whom he should appoint as federal judges and prosecutors.

In combination, these two aspects of the job, representing the U.S. and advising the cabinet departments, mean that the attorney general plays a key role in helping the president perform his constitutional duty to take care that the laws of the United States are faithfully executed.

115,000 employees

Since 1870, attorneys general have had an entire executive department – the Department of Justice – to help them execute their duties.

Today’s department contains over 70 distinct offices, initiatives and task forces, all of which the attorney general supervises. There are currently 115,000 employees in the department.

The DOJ contains litigation units divided by subject matter like antitrust, civil rights, tax, and national security. Each of these units conducts investigations and participates in federal lawsuits related to its expertise.

The Justice Department also has several law enforcement agencies that help ensure the safety and health of people who live in the United States. The most well-known of these agencies include the FBI, the Drug Enforcement Administration and the U.S. branch of the International Criminal Police Organization, known as Interpol.

Additionally, the DOJ contains corrections agencies like the Federal Bureau of Prisons and the U.S. Parole Commission. These agencies work to ensure consistent and centralized coordination of federal prisons and offenders.

Finally, the department manages several grant administration agencies. These agencies, such as Community Oriented Policing Services, the Office of Justice Programs and the Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking (SMART), provide financial assistance, training and advice to state, local, tribal and territorial governments as they work to enforce the law in their own communities.

Separating politics from law

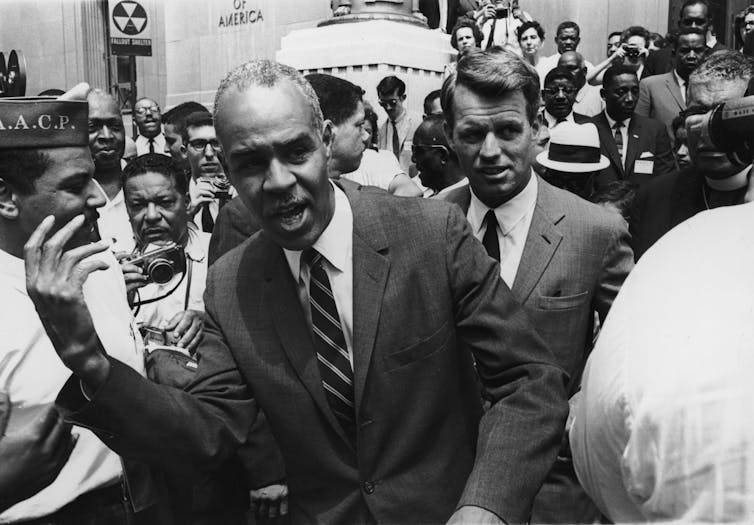

Given all the attorney general’s responsibilities, the role is both political and legal. As such, attorneys general historically have a difficult task in separating their jobs as policy adviser from their duties as chief legal officer of the United States.

For example, President George W. Bush’s attorney general, Roberto Gonzales, resigned from office amid accusations of the DOJ’s politicized firing of U.S. attorneys and misuse of terrorist surveillance programs. And Loretta Lynch, President Barack Obama’s attorney general, was criticized for meeting privately with former President Bill Clinton while former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was under investigation by the DOJ.

The attorney general’s job is complicated by the fact that the president has the constitutional power to fire them for political reasons.

During his first term, Trump replaced Attorney General Jeff Sessions after Sessions angered Trump by recusing himself – removing himself – from overseeing the Mueller investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election.

Given the attorney general’s connection to the president and the attorney general’s position as the head of the DOJ, critics see Trump’s nomination of Pam Bondi as a key part of his plan to control the department’s agenda, including through the use of the FBI to pursue his perceived enemies.

There is good reason for critics to question the relationship between the president and attorney general. As Kristine Olson, former U.S. attorney for the District of Oregon, wrote in the Yale Law and Policy Review, “The President’s power to appoint the Attorney General of the United States as a member of the Cabinet subject to dismissal contains the seeds of a fundamental rule of law crisis in the politicization of the U.S. Department of Justice.” In the past six presidential administrations, Olson writes, many attorneys general have yielded to presidential and political pressure when performing their jobs.

But some have not. For example, in large part because of her reputation for high ethical standards when navigating the job, Janet Reno – President Clinton’s attorney general – was the longest-serving attorney general in the 20th century.

Whether the Senate will confirm Bondi or someone else as the next attorney general puts the fate of the nation’s top law enforcement official in the hands of politicians.

This story is part of a series of profiles of Cabinet and high-level administration positions.

Jennifer L. Selin has received funding and/or support for her research on the executive branch from the Administrative Conference of the United States. The views in this piece are those of the author and do not represent the position of the Administrative Conference or the federal government.

Read These Next

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…

Why US third parties perform best in the Northeast

Many Americans are unhappy with the two major parties but seldom support alternatives. New England is…

Detroit was once home to 18 Black-led hospitals – here’s how to understand their rise and fall

In the early 20th century, Detroit’s Black medical professionals created a network of health care…