Nevada is a battleground state – and may be a bellwether of more extreme partisanship

From one perspective, Nevada’s political history is balanced. From another, it’s s pendulum swinging back and forth as people split their votes across party lines.

Over the course of Nevada history, no one party has dominated the state’s politics, and its electorate has remained surprisingly balanced in its political leanings. Since becoming a state in 1864, Nevada has had equal representation with its federal delegation: 14 U.S. senators from each of the major parties and 20 U.S. House members from each of the Democratic and Republican parties.

The same parity exists at the state level. There have been 31 governors of Nevada: 15 Republicans, 12 Democrats and two each from the Silver Party – active around the turn of the 20th century – and the Silver Democrat Party. The Silver Democrats were eventually absorbed into the Democratic Party.

While the state Senate has been controlled by Republicans 48 times and Democrats 28 times, the proportional control of the state Assembly is the reverse, with Democrats controlling the chamber 50 times and Republicans in the majority 26 times.

That all adds up to an unusual status for Nevada in today’s politics: It is neither a red state nor a blue state. And that has led some to label it a battleground state for the 2024 presidential election.

However, as a longtime Nevadan and a scholar who studies political systems, I have seen Nevada become more polarized along party lines. Will this growing polarization move the state away from its historic political evenhandedness?

The economy, specifically concerns about inflation, gas prices and housing affordability, is top of mind for Nevada voters. Republicans argue that the economy is getting worse, while Democrats contend it is improving. And controversial issues likely to appear on the November 2024 ballot – abortion rights, requiring voter identification and allowing teachers to strike – have contributed to the polarizing rhetoric of local and statewide races.

Balanced from the widest angle

Taking a wide view of Nevada politics, political representation from both of the major parties appears balanced. However, a closer look reveals a shifting landscape over the past couple of decades.

Culturally, Nevada has been associated with easy marriage and divorce, casino gambling, legal prostitution and a loose, anything-goes mentality – all captured by the famous slogan “What happens here, stays here.”

In reality, Nevada has also been politically conservative, even among Democrats. This cauldron of conflicting images has resulted in a political landscape that has shifted between Republican and Democratic domination at both the federal and state levels.

From Nevada’s ascension to statehood in 1864 until 1890, Republicans led the state. All federal and state representatives except for two legislators were Republican in 1864, when Nevada became the 36th state.

From 1890 to 1908, Nevada was governed by the Silver Party, which advocated for the unlimited coinage of silver, a major economic issue in the U.S. in the late 19th century. By 1902, most pro-silver factions in Nevada had been absorbed by the state Democratic Party.

From 1908 until 1930s, Republican and Democratic control were roughly equally divided, with Democrats winning more positions but Republicans securing more top-of-the-ticket victories at the presidential and gubernatorial levels.

After the election of Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932, Democrats dominated Nevada politics until the 1980s, when Republicans reemerged; by late 1995, Republican voter registrations outnumbered Democrats in Nevada for the first time since the 1930s.

However, by 2004, the political tides had shifted back to Democrats due to strong get-out-the-vote efforts by the Democratic Party.

Nevada is a really strong union state. The Culinary Union, which represents over 60,000 Nevada hospitality workers, is particularly influential. The “Reid machine,” a loose coalition of progressive groups named after the late U.S. Senate majority leader Harry Reid, began working in the mid 1990s, with the Culinary Union pushing to register its working class, young, Latino, Black and Asian members as voters. These efforts intensified after losses by the Democrats in 2002. Together, the union and the progressives then worked to make sure that people voted – by early voting, in-person on Election Day or by mail.

These efforts have most noticeably affected the state Legislature, where Democrats have almost always been in control of the state Assembly since 1997, save for one two-year session in 2015, and have led the state Senate since 2009, except for that 2015 session.

Splitting the ticket

Nevada’s federal delegation since 2019 has been dominated by Democrats, who have held three of the four U.S. House of Representatives seats and both U.S. Senate seats. However, despite the increase in Democratic registration and the efforts of the “Reid machine,” nearly all governors elected since 1998 have been Republicans. The lone exception was the election of Democrat Steve Sisolak for one four-year term in 2018.

These party differences among federal and state officeholders happen because Nevadans are well-known ticket splitters, priding themselves for voting more on the basis of issues and personalities over party loyalties or identity.

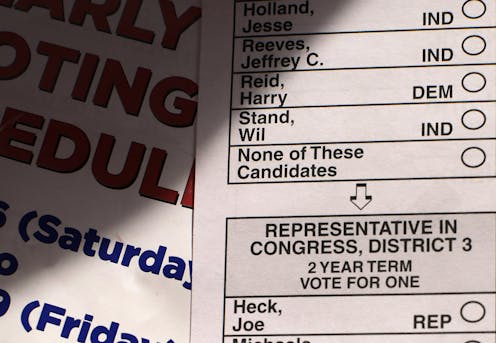

And to demonstrate Nevadans’ political independence, in 1976 the state added “None of These Candidates” as a choice for all statewide and federal offices. It is the only state in the U.S. with this option.

Nevada’s voting patterns have meant the state’s voters have fairly reliably chosen the winner in presidential elections. Of the 40 presidential elections in which Nevada has participated from 1864 to 2020, the state voted for the winning candidate 33 times. And in the 23 presidential elections since 1912, its electoral votes have gone to the winning presidential candidate in all but two elections – in 1976 and 2016.

Looking to the coming election

At the federal level, current polling has Nevadans splitting their votes in November 2024. Former President Donald Trump is ahead of Joe Biden by about 5 percentage points, while U.S. Senator Jacky Rosen, the Democratic incumbent, is leading her challenger, Republican Sam Brown, by over 10 percentage points.

The “Reid machine” still exists, but its power has been waning since the former senator’s death in 2021. The Culinary Union, which customarily has been aligned with Democrats, is feuding with the Nevada Democratic Party over its 2023 support for repealing a 2020 COVID-era state law that mandated frequent room cleaning. This has led to the union’s refusal to endorse a number of Democratic state representatives. While this does not mean the union will support Republicans, the dispute could reduce the union’s get-out-the-vote efforts.

In addition, nonpartisans now outnumber registered voters in both the Democratic and Republican parties in Nevada. Data from the Nevada Secretary of State’s office shows that nonpartisans comprise 33.8% of active registered voters, compared with 30.3% who are Democrats and 28.8% who are Republicans. As my research has confirmed, independents are notoriously unpredictable with their votes.

Nevada is unique in that it is one of the most working-class states in the country. Demographically, it is reasonably reflective of the country as a whole. It has high populations of Latino and Asian American people, and both parties are in competition for these voters.

The growing number of voters leaving the two major parties and identifying as independent, coupled with the expanding divide of the two major political parties and polarizing political rhetoric, may be more reflective of where the rest of the states are heading.

Nevada may remain a battleground state due to its political divide, but the rise of nonpartisan voters in the state may signal where the national electorate is heading.

Thom Reilly does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…

Why US third parties perform best in the Northeast

Many Americans are unhappy with the two major parties but seldom support alternatives. New England is…

Abortion laws show that public policy doesn’t always line up with public opinion

Polls indicate majority support for abortion rights in most states, but laws differ greatly between…