Did Biden really steal the election? Students learn how to debunk conspiracy theories in this course

A scholar of history of education and American politics explains what is behind his course on conspiracy theories and how students learn to debunk fake ideas.

Uncommon Courses is an occasional series from The Conversation U.S. highlighting unconventional approaches to teaching.

Title of course:

Debunking conspiracy theories

What prompted the idea for the course?

I am interested in how people internalize or learn about political beliefs they go on to adopt. This interest coincided with my concerns about the seeming ease with which some far-right conservatives and supporters of former President Donald Trump peddled patently bogus conspiracies about election fraud in 2020.

One of the outcomes of these schemes was Trump supporters’ attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Sadly, the belief that the 2020 presidential election was fraudulent, even in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, has remained one core element of the Trump 2024 campaign. I remembered the work of historian Richard Hofstadter, who coined the term the “paranoid style” in politics in a Harper’s Magazine essay in 1964. His main idea was that some politicians were using fear and a paranoid style of thinking to sway voters. They refused to accept the current state of society and wanted to make it appear that there was a looming threat to the country.

Hofstadter’s work was prompted by the actions of an extreme right-wing movement called the John Birch Society. I had a feeling of déjà vu with Trump.

What does the course explore?

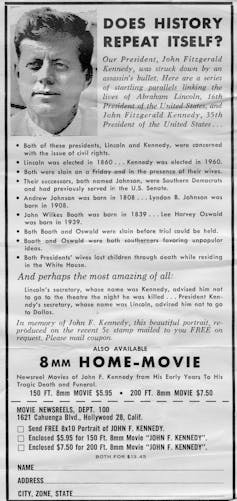

What’s the real truth about the moon landing? Who really killed JFK? These are just some of the questions we explore in this course. My goal is to balance the serious with the absurd.

I want students to identify the root causes of the conspiracy, use vetted sources and learn to be good consumers of online information.

I also want to train students in the practice of critical analysis. The American Psychological Association has shown that people who practice conspiratorial thinking are more likely to seek simple solutions to complex problems and experience feelings of fear and isolation.

We begin the course examining what we can learn from both political science and psychology. We look at the long history of hoaxes, frauds and deliberate conspiracies in American history, stretching back to the Illuminati, anti-Catholicism and antisemitism.

What is old is new again. The idea that a mysterious group like the Illuminati is secretly in control of the world has not gone away. False beliefs about various groups such as Catholics and Jews are, sadly, recycled again and again.

The course also covers the current conspiracy theories about Taylor Swift. This includes the false belief that the outcome of the February 2024 Super Bowl was predetermined so that the Kansas City Chiefs would win, and Swift, the girlfriend of Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce, would announce her support for President Joe Biden.

My course also explores much more serious threats, like QAnon – a dangerous movement that falsely believes secret government operatives are running child sex rings.

We also take a look at topics like UFOs, aliens, Bigfoot and the Loch Ness monster.

Why is this course relevant now?

In the current age of political polarization, it is critical that I do all I can to equip future leaders and citizens with the tools they need to suss out fact from distraction and outright fiction.

What’s a critical lesson from the course?

My hope is that my students leave the course with the confidence that they need to not only recognize but to openly combat disinformation. We live in an age of oversaturation of information. My students are digital natives. They rarely receive information from traditional media outlets like newspapers. When one considers the wealth of disinformation on the internet, or the prospect that TikTok is their primary source of news, it is critical that students are educated about how to evaluate information.

What materials does the course feature?

I use a number of resources in this class, including magazine articles, academic papers, books and websites that give people tools to recognize false information.

Our reading list includes the books “A Culture of Conspiracy: Apocalyptic Visions in Contemporary America,” “Enemies Within: The Culture of Conspiracy in Modern America” and “The Paranoid Style in American Politics and other essays”.

What will the course prepare students to do?

My students will feel some discomfort at times confronting their own biases and preconceived notions.

The idea is that my course will prepare students to question and then determine the veracity of patently false information. My students will also be prepared to recognize that most conspiracies are born from conditions of stress and the fear of the other.

David Cason does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Why ICE’s body camera policies make the videos unlikely to improve accountability and transparency

For body cameras to function as transparency tools, wrongdoing would have to be consistently penalized,…

Artists and writers are often hesitant to disclose they’ve collaborated with AI – and those fears ma

Whether they’re famous composers or first-year art students, creators experience reputational costs…

Honoring Colorado’s Black History requires taking the time to tell stories that make us think twice

This year marks the 150th birthday of Colorado and is a chance to examine the state’s history.