In Kyrgyzstan, creeping authoritarianism rubs up against proud tradition of people power

Recent laws and pro-Putin sentiment by Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov have sparked concern that the Central Asian country is backsliding on democracy.

The people of Kyrgyzstan have a well-earned reputation for “street democracy.”

Since emerging from the breakup of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, citizens in the Central Asian republic have taken it upon themselves to oust presidents who attempt to overstay their welcome or engage in corruption.

Indeed, between 2005 and 2020, the country experienced five presidential transitions – three as a result of popular protests and two through the peaceful democratic transfer of power.

But a new trend appears to be in the air of Bishkek, the country’s capital. In contrast to how he is viewed in some other former Soviet states, Russian President Vladimir Putin is popular among Kyrgyz, and his strongman style appears to be influencing the country’s rulers. In recent weeks, legislation has been advanced to extend their authority and crack down on dissent.

As a scholar of democracy, civic activism and post-Soviet geopolitics, I’ve long known about Kyrgyzstan’s distinctive trajectory – and wondered how this track record of people power squares with recent moves toward authoritarianism. I learned more during a visit to the country in the fall.

Protest spaces

The epicenter of Kyrgyz street politics is Bishkek’s Ala-Too Square and the adjacent White House, which historically served as the official presidential office building.

In 2005, Kyrgyz citizens gathered there to protest against their first post-Soviet president, Askar Akayev, when he tried to circumvent term limits and extend his power. The “Tulip” revolution drove Akayev into exile in Moscow.

Five years later at the same location, people gathered for the People’s April Revolution against corruption-charged President Kurmanbek Bakiyev.

Bakiyev authorized deadly force against protesters before being toppled. About 90 protesters who were killed are commemorated to this day with a striking monument on Ala-Too Square.

The square became an epicenter of discontent again in 2020, when anti-government protests overturned what many citizens saw as a stolen election and forced President Sooronbai Jeenbekov from power.

A new brand of politics

Kyrgyzstan’s current president, Sadyr Japarov, knows this history well: He lived it.

After serving in Bakiyev’s administration, he helped lead mass demonstrations in 2012 against newly elected President Almazbek Atambayev.

After participating in an armed attempt to storm Parliament, Japarov fled the country. Upon his return to Kyrgyzstan in 2017 he was jailed, but he established a new political party from prison.

In January 2021, Japarov won the presidential election with almost 80% of the vote, having run on a populist platform that included pledges to crack down on corrupt elites and foreign corporations.

But Japarov also stressed the importance of Kyrgyzstan’s special relationship with Russia. And increasingly his style of leadership has taken a leaf out of Putin’s playbook. The presidential vote in 2021 was accompanied by a referendum that increased the power of the office and reduced the importance of Parliament.

Japarov is making that shift concrete: He is constructing a new presidential building about 5 miles south of the city center, reducing the potential for street politics to factor so largely in the country’s future.

During my October visit, other signs were apparent of Japarov’s determination to reshape Kyrgyz politics. On Oct. 4, 2023, security forces shot and killed leading crime boss Kolya Kolbaev in a Bishkek pub he owned. State media represented this as a crackdown on organized crime, consistent with Japarov’s election promises. But to many Bishkek citizens, it was less of a crackdown and more a takeover of Kolbaev’s lucrative criminal operations by the Kyrgyz state.

A week later, there was another potential display of Kyrgyzstan’s drift away from people power. Bishkek’s kindergartens, schools and colleges were abruptly ordered to close or operate only online on Oct. 12 and 13.

The measure coincided with Bishkek’s hosting the annual meeting of the Commonwealth of Independent States, which Putin, making his first international trip since the International Criminal Court issued a warrant for his arrest, was due to attend.

Officially, the closures were simply to ease congestion. But I heard locals speculate that authorities acted to forestall any youth-led protests against the country’s prominent and potentially divisive guest. The authorities instituted a similar measure on Oct. 25 and 26 during a visit by China’s Premier Li Qiang.

Also in October, Parliament discussed proposed laws that closely resemble legislation introduced by Putin in Russia. The bills would curtail freedom of expression and empower the government to prosecute or shut down any organization it identifies as being a “foreign representative.”

Despite protest from Kyrgyz and international media freedom groups, the United Nations and the U.S. – which expressed its concerns in a letter, prompting Japarov to accuse Washington of meddling – the laws keep moving forward. In a controversial Parliament vote in late February 2024, 62 votes to advance the law were passed by the 50 members present, some of whom cast votes for their absent colleagues.

The resilience of memory

In intimidating Parliament, eliminating powerful rivals and cracking down on free media, Japarov is not only adopting many of Putin’s methods, he is taking a calculated bet against the country’s recent history of democratic activism.

On the surface, the odds are in the government’s favor. Compared with other post-Soviet states, Putin still commands high approval ratings in Kyrgyzstan. After a decade and a half of political turbulence – as well as widespread corruption and organized crime – Japarov’s “strongman” persona is appealing for many.

But for many other Kyrgyz citizens, cozying up to Russia raises concerns.

After all, Georgia and Ukraine were also founder members of the Commonwealth of Independent States. Both have since been attacked by Putin’s Russia.

The 2022 brutal invasion of Ukraine has sparked direct parallels with Russian and Soviet attempts to eliminate Kyrgyz culture over two centuries.

Bishkek – then known as Pishpek – came under Russian rule in the 1850s as the czar conquered a patchwork of Central Asian city-states and nomadic tribes under the guise of a “civilizing mission.”

The Kyrgyz people continued to defend their distinctive nomadic way of life. But overt resistance against Russian rule was met with brutal force. In 1916, when imperial Russia began forcibly conscripting Kyrgyz men to fight in World War I, Kyrgyz rebelled. In the crackdown that followed, over 100,000 Kyrgyz were killed. Many women and children died crossing the Tian Shan mountains to seek refuge in China from Russian repression.

Soviet rule ostensibly offered the promise of better relations with Moscow. And in 1926, the Kyrgyz gained autonomy; full republic status followed in 1936.

In common with much of the Soviet Union, Kyrgyz citizens suffered from Stalin’s purges. In 1938, 138 Kyrgyz intellectuals were killed and buried in a mass grave outside Bishkek, where Stalin’s victims are remembered, alongside other Kyrgyz patriots, at the Ata-Beyit memorial near Bishkek.

This commitment to preserving memory, combined with a deep distrust of authoritarian overreach, anchors Kyrgyz citizens. But it rubs up against where the country finds itself today: in a pivotal place amid shifting geopolitics.

The U.S. and Russia are vying for influence in Central Asia, while China, Turkey and the Persian Gulf states are also making significant investments in the region.

As Kyrgyzstan’s leaders seek to maintain sovereignty, develop and diversify the economy and improve the country’s standing in the world, they face difficult choices. For now, they seem to be following Putin’s path.

Keith Brown is Director of the Melikian Center, which receives funding from the US Departments of Education, Defense and Education. He traveled to Bishkek as part of a research project that is supported by the U.S. Russia Foundation, a legacy organization of the U.S. Russia Investment Fund, founded by the U.S. Government.

Read These Next

Honoring Colorado’s Black History requires taking the time to tell stories that make us think twice

This year marks the 150th birthday of Colorado and is a chance to examine the state’s history.

Supreme Court’s Michigan pipeline case is about Native rights and fossil fuels, not just technical l

The issue in front of the US Supreme Court is seemingly mundane, about federal or state jurisdiction.…

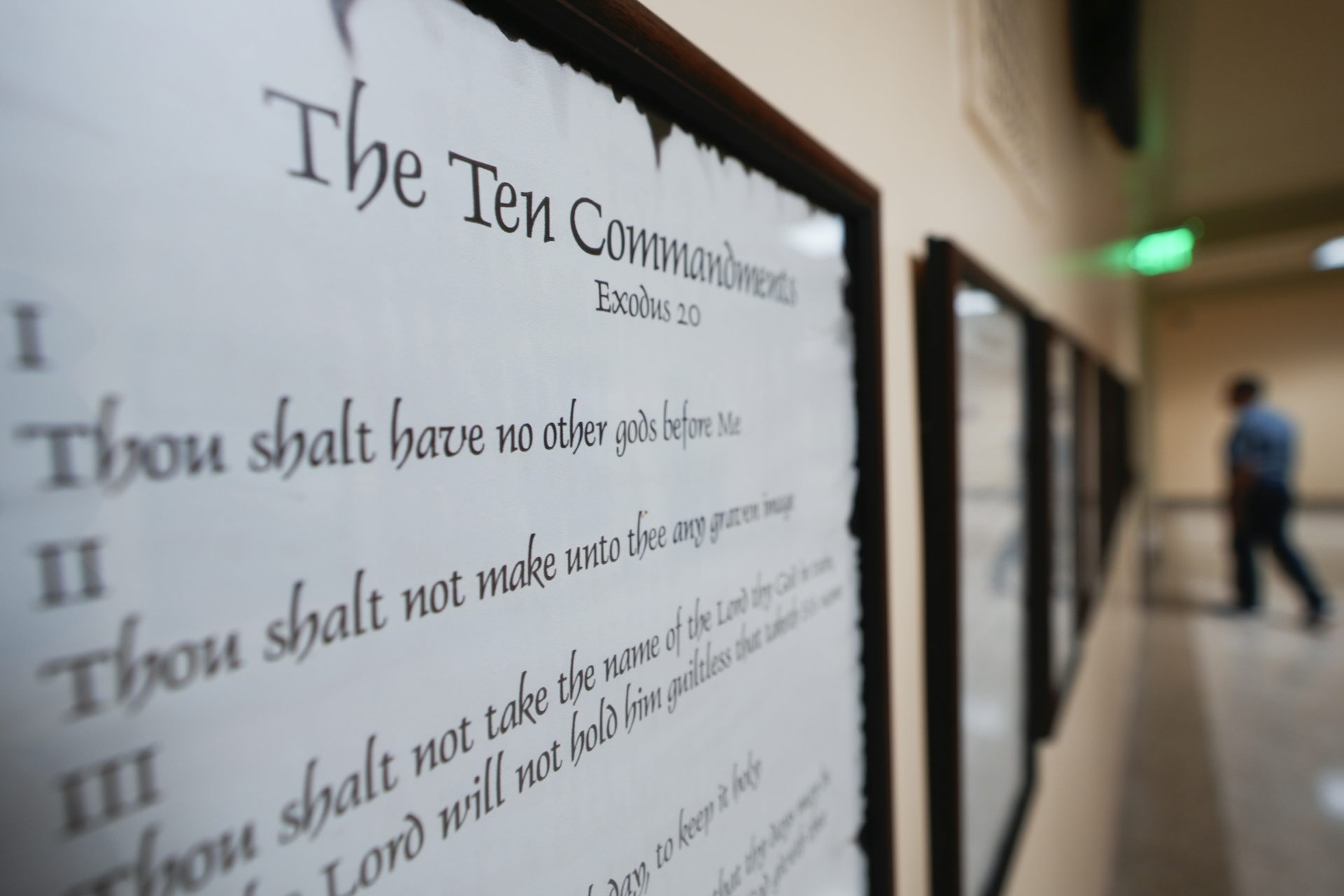

Baptists have helped shape debate about religious freedom for over 400 years – up to today’s 10 Comm

The phrase ‘separation of church and state’ dates back to a letter from Thomas Jefferson to a Baptist…