Belief in the myth of outlaw heroes partly explains Donald Trump’s die-hard support

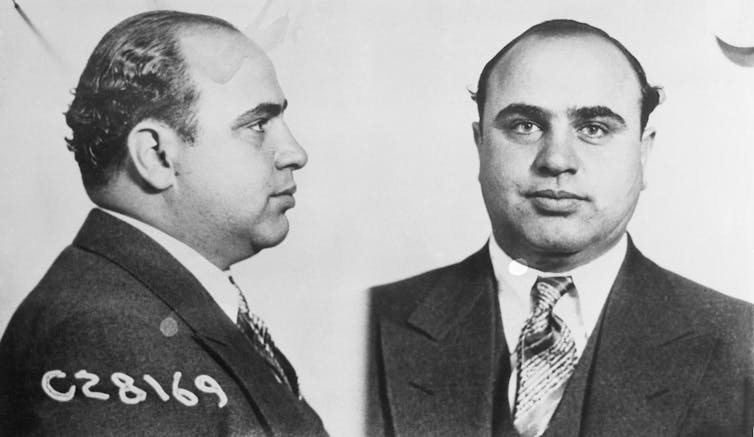

From Robin Hood to Al Capone, outlaw heroes have played a significant role in American culture. Trump claims he is one of them.

Before Donald Trump likened himself to Russian dissident Alexei Navalny, the former president frequently compared himself with a completely opposite personality – Chicago organized crime boss Al Capone.

During a speech in Nevada in December 2023, Trump painted himself as the victim of overzealous prosecutors who have treated him worse than one of the nation’s most notorious criminals.

“He got indicted once,” Trump told followers. “I got indicted four times. Over bullshit, I got indicted.”

In his never-ending attempt to politicize his substantial legal troubles, Trump’s exaggerated claims of victimhood are part of the appeal to his die-hard MAGA followers, who believe what Trump tells them: He is being persecuted by deep state bureaucrats because he is fighting for them.

“Never forget,” Trump said. “Our enemies want to take away my freedom because I will never let them take away your freedom … they are not after me. They’re after you. And I just happened to be standing in their way.”

The message that Trump is serving as a protector against unexplained foes is part of the myth of an outlaw hero. Belief in such characters may explain his unwavering support and commanding lead in the 2024 race for the GOP presidential nomination.

American Robin Hoods?

In moments of high drama, the outlaw hero is a recurring figure throughout history.

Wherever they appear, outlaw heroes symbolize resistance to perceived changes to a way of life. Most often, these heroes emerge locally from humble roots and gather visibility and celebrity as a result of their daring, audacious acts that become the stuff of legends.

The common theme in all these outlaw hero legends is that they claim to be engaged in campaigns to restore justice by taking from the powerful and giving to the powerless at great personal risk.

The model for American outlaw heroes is England’s Robin Hood. As the legend goes, he stood against the corruption and tyranny of the Sheriff of Nottingham by robbing from the rich and giving to the poor.

In America, during the 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a series of outlaw heroes, from Jesse James and William “Billy the Kid” Bonney to John Dillinger and Al Capone, around whom similar legends developed – that they stood up to unjust authorities in ways that were daring, captivating the imagination of many Americans.

But the reality of their lives was completely different than the myths.

They were constantly on the run from law enforcement authorities. While their daring jail escapes and bank robberies drew cheers from supporters, their lives were filled with dangerous shootouts, often ending in sudden deaths. In Capone’s case, it ended after years fighting dementia and other complications from syphilis.

John Dillinger, for instance, the notorious bank robber who gained fame during the roaring 1920s, was shot to death by FBI agents on July 22, 1934, after one such shootout.

Though these outlaw heroes may have targeted the rich and powerful, there is scant evidence that the riches they accumulated were ever redistributed to the poor. But the banks they robbed held the savings of ordinary people, and the violence they fomented took place in their local communities.

Capone is one example.

By the late 1920s, he had cultivated an image of a well-intentioned businessman who cared only about the welfare of his fellow Chicagoans.

In reality, Capone was the nation’s most visible mobster who violently protected his criminal enterprise of gambling and selling alcohol during the Prohibition era. Among the best examples of Capone’s ruthlessness was the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre on Feb. 14, 1929. Posing as policemen, members of Capone’s gang lined up seven rivals against a wall and machine-gunned them to death.

Throughout his life, Capone was indicted and convicted of several crimes, including tax evasion, contempt of court, carrying concealed weapons and bootlegging alcohol. He ultimately died on Jan. 25, 1947, at the age of 48.

Trump’s outlaw behavior

This disparity between life and legend exists because outlaw heroes were both celebrated by supporters and condemned by authorities. The result, then and now, is that each side has been baffled by the other’s inability to see the truth.

The key to understanding outlaw heroes, then, is that they flourish not in spite of but rather because of their rebelliousness. The more daring and rebellious the outlaw hero, the more commanding the figure becomes.

Such is the case with Trump.

Despite his personal and family wealth, Trump has been able to convince his blue-collar supporters that he is one of them. He presents himself as a persecuted figure who stands between them and politically motivated “witch hunts.”

As their champion, Trump has been excused for the kinds of behaviors that have brought down other political figures.

Those behaviors include marital infidelity and sexual abuse, evading taxes and avoiding military service, disparaging celebrated and wounded military veterans and threatening his political opponents with lawsuits, imprisonment or execution.

In addition, Trump faces four criminal indictments that range from his efforts to remain in power following the 2020 presidential election to his alleged willful retention of classified documents.

What most distinguishes Trump from earlier outlaw heroes is that he has actually captured the nation’s most powerful position and is now campaigning to reclaim it.

Though the final chapter of the Trump saga has yet to be written, there is the very real possibility that Trump, like outlaw heroes before him, will become larger in legend after death than he was in life.

David G. Bromley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Taboo tics like shouting curses and slurs are uncommon in Tourette syndrome − but people who have th

Obscene language tics, called coprolalia, don’t reveal what people with Tourette’s think and feel.…

Artists and writers are often hesitant to disclose they’ve collaborated with AI – and those fears ma

Whether they’re famous composers or first-year art students, creators experience reputational costs…

Honoring Colorado’s Black History requires taking the time to tell stories that make us think twice

This year marks the 150th birthday of Colorado and is a chance to examine the state’s history.