Biden’s use of military in Yemen upsets congressional progressives, but fits with long tradition of

In the wake of US attacks against Houthi militants in Yemen, a scholar of presidential power to use the military examines the history and present of the laws around US military action.

Amid ongoing U.S. missile attacks against Houthi militants in Yemen in January 2024, progressive Democrats in Congress have objected to President Joe Biden’s failure to seek congressional approval before conducting military operations.

They note that Article I of the U.S. Constitution gives Congress the power to declare war, and say that section requires Biden to seek prior authorization for military action.

But Biden’s public statement about the strikes he ordered and his letter notifying Congress that they had happened indicate he disagrees. Instead, Biden has the same view as most modern presidents: Article II of the Constitution allows him to use the military in certain situations without prior approval from Congress.

By this reading of the text, presidents, as commander in chief, claim the power to unilaterally order the military to initiate small-scale operations for a short duration. Members of Congress may object to that claim, but they have done little to limit presidents’ authority. What little they have done has not been effective.

As I’ve demonstrated in my research, even though the 1973 War Powers Resolution attempted to constrain presidential power after the disasters of the Vietnam War, it contains many loopholes that presidents have exploited to act unilaterally. For example, it allows presidents to engage in military operations without congressional approval for up to 90 days. And more recent congressional resolutions have broadened executive control even further.

A long tradition of executive authority

Presidents can even overcome the loopholes in the War Powers Resolution if the operation lasts longer than 90 days. In 2011, a State Department lawyer argued that airstrikes in Libya could continue beyond the War Powers Resolution’s 90-day time limit because there were no ground troops involved. By that logic, any future president could carry out an indefinite bombing campaign with no congressional oversight.

While every president has bristled at congressional restraints on their actions, presidents since Franklin D. Roosevelt have successfully circumvented them by citing vague concerns like “national security,” “regional security” or the need to “prevent a humanitarian disaster” when launching military operations. While members of Congress always take issue with these actions, they never hold presidents accountable by passing legislation restraining him.

In Biden’s case, he has said the U.S. actions, including major attacks against the Houthis on Jan. 11 and 18, 2024, were defending civilian commercial vessels traveling through the international waters of the Red Sea.

Much like his predecessors, Biden did not provide Congress with more concrete information about the nature of the operation or its expected duration.

The push-and-pull between Congress and the president over military operations dates back to the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack, which led Congress to declare war on Japan. Before then, Congress had prevented the U.S. from joining World War II by enforcing an arms embargo after 1939 and refusing to help the Allies prior to the attack at Pearl Harbor. But afterward, Congress began allowing the president to take more control over the military.

During the Cold War, rather than returning to a balanced debate between the branches, Congress continued to relinquish those powers.

Congress never authorized the war in Korea; Harry Truman used a U.N. Security Council resolution as legal justification. Congress’ vote explicitly opposing the invasion of Cambodia didn’t stop Richard Nixon from doing it anyway. Even after the Cold War, Bill Clinton regularly acted unilaterally to address humanitarian crises or the continued threat from leaders like Saddam Hussein. He sent the military to Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia and Kosovo, among other places.

After 9/11, Congress quickly gave up more of its power. A week after those attacks, Congress passed a sweeping Authorization for Use of Military Force, giving the president permission to “use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001.”

In a follow-up 2002 authorization, Congress went even further, allowing the president to “use the Armed Forces … as he determines to be necessary and appropriate in order to defend national security … against the continuing threat posed by Iraq.” This approach provides few, if any, congressional checks on the control of military affairs exercised by the president.

In the two decades since those authorizations, four presidents have used them to justify all manner of military action, from targeted killings of terrorists to the yearslong fight against the Islamic State group.

Congress regularly discusses terminating those authorizations, but has yet to do so. If Congress did, the loopholes in the original War Powers Resolution would still exist.

Since becoming president, Biden has claimed to support the repeal of the authorizations, and supported more congressional oversight of military actions. But he has used the authorizations’ power to launch a drone strike in Somalia against fundamentalist al-Shabab fighters, as well as claiming he had the constitutional power to act unilaterally to defend U.S. forces in Syria.

More recently, Biden has extended his use of military power, and not just against the Houthis. In early 2024 he used the 2002 authorization as a legal rationale for the targeted killing of Iranian-backed militiamen in Iraq, a strike condemned by Iraqi leaders.

Those actions may have ruffled congressional feathers, but they are in keeping with a long U.S. tradition of targeting members of terrorist groups and protecting members of the military serving in a conflict zone.

Threats of war

The U.S. is not simply punishing the Houthis for actions that the Houthis say are supporting the Palestinian cause against the Israelis.

It’s taking on an Iranian-backed militant group. That means the U.S. is risking conflict with a larger enemy whose tentacles reach all the way to Russia and even to China.

Iran itself may also be spoiling for a fight with the U.S. In 2020, President Donald Trump ordered a lethal drone strike against a respected member of the Iranian government, Major General Qassim Soleimani, the head of Iran’s equivalent of the CIA, without consulting Congress or publicly providing proof of why the attack was necessary, even to this day.

Tensions – and fears of war – spiked but then slowly faded when Iran responded with missile attacks on two U.S. bases in Iraq. However, Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Hosseini Khamenei has continued to vow to get revenge for Soleimani’s killing. That leaves open the possibility that Iran could see U.S. actions against the Houthis or support for the Israelis as a justification for addressing the Soleimani strike more forcefully.

If that occurs, under the current legal structure, Biden could craft the U.S. response without congressional notification or approval.

This article includes material from an article originally published on July 29, 2021.

Sarah Burns receives funding from the Institute for Humane Studies.

Read These Next

Honoring Colorado’s Black History requires taking the time to tell stories that make us think twice

This year marks the 150th birthday of Colorado and is a chance to examine the state’s history.

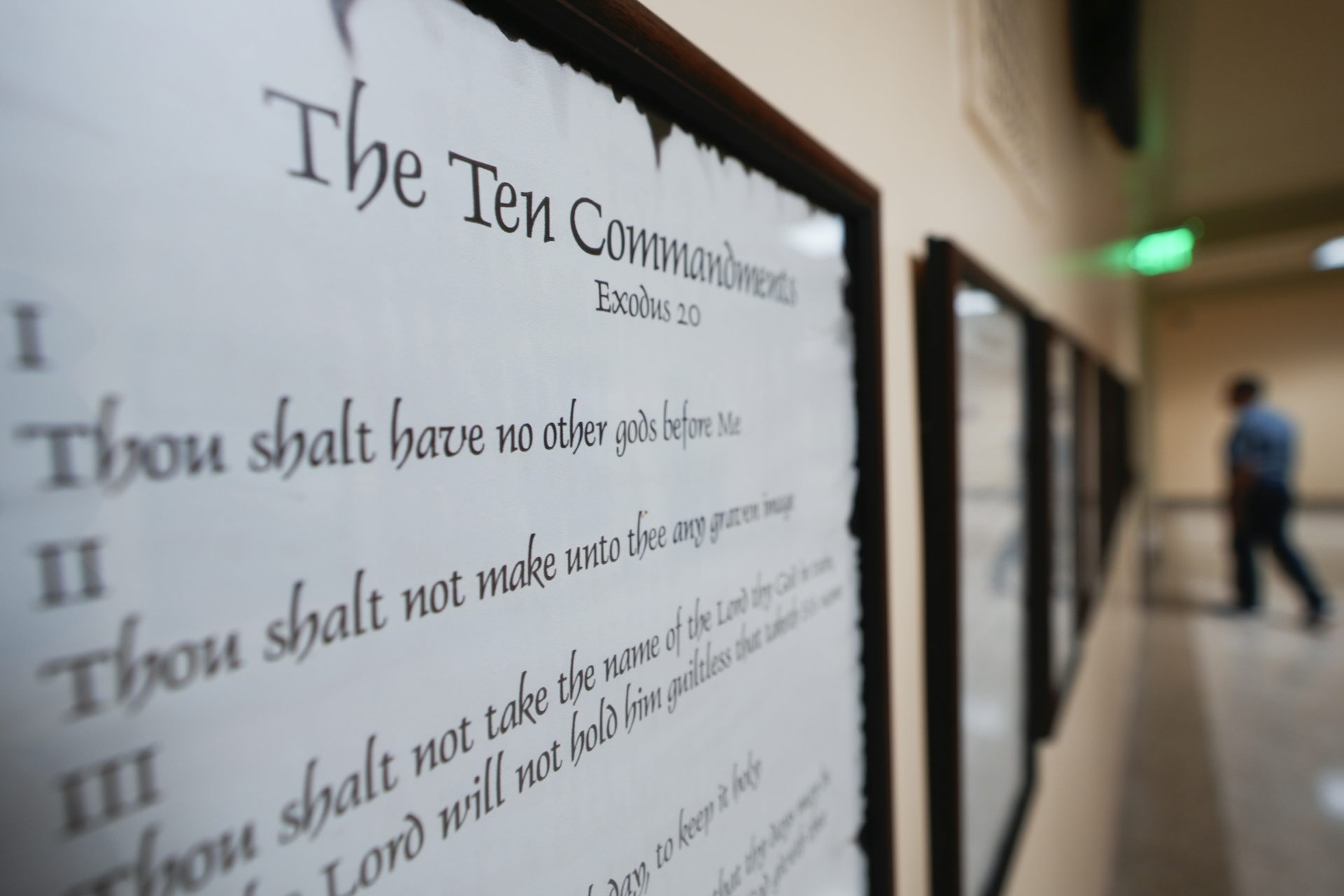

Baptists have helped shape debate about religious freedom for over 400 years – up to today’s 10 Comm

The phrase ‘separation of church and state’ dates back to a letter from Thomas Jefferson to a Baptist…

Why standing in solidarity with immigrants is an act of accompaniment in Catholic philosophy

Accompaniment, rooted in modern Catholic social thought, calls for putting the needs of the most vulnerable…