I study migrants traveling through Mexico to the US, and saw how they follow news of dangers – but a

A fire killed 38 migrants in a Mexico detention facility in March 2023. A sociologist’s conversations with migrants show that they had a common response to this news – a deep sense of grief.

The world awoke one morning in late March 2023 to the news that at least 38 Central and South American migrants had died in a fire in a migrant detention center in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

A widely circulated video from the closed-circuit cameras inside the detention center showed the building burning, with migrants trapped inside trying to break the metal bars of their cells – and detention center officers allegedly leaving them there.

The Mexican government has said the migrants themselves started the fire after learning they would be deported from Mexico – which is increasingly a destination for migrants and asylum seekers – back to their home countries.

The video spread quickly across social media, and many Mexican migrant advocacy groups and activists decried the event.

Another group also paid close attention to this tragedy – migrants who are in transit through Mexico.

As a sociologist, I have studied the impacts of violence against Central American migrants in Mexico for nearly a decade. I have considered questions like how migrants who are on their way to the U.S. react to news of violence against other migrants, and whether such news alters their plans.

My research has shown that migrants pay close attention to any information that can give them clues about the dangers that lie between them and the U.S.

Migrants have shared with me that they highly value information about any dangers ahead as they move north, whether it relates to criminal groups or U.S. immigration policy changes. Migrants use this knowledge to implement a variety of strategies to avoid, or at least prepare for, any suffering – and it can lead them to take different routes to the U.S. border.

Understanding migrants in Mexico

Hundreds of thousands of migrants from around the world transit through Mexico every year on their way to the U.S.-Mexico border. In April 2023 alone, the U.S. detained more than 211,000 migrants along that border. That statistic coincides with an overall rise in global migration and rise in migrants trying to reach the U.S..

The majority of migrants crossing the U.S. border come from Latin American countries other than Mexico, including Central American countries, but also Peru, Colombia, Venezuela and Cuba.

Most of these migrants are single adults, though a number of them are also families and children. People migrate through Mexico for many reasons, including political instability, lack of work opportunities and violence in their own countries.

My interviews with migrants moving through Mexico show that they tend to widely circulate tragic news, such as news of the June 2022 news of migrants found dead locked in a tractor trailer in San Antonio. Videos and photos of this and other tragic instances, like the Ciudad Juárez fire, provide real, vivid images of what can happen if migrants decide to pursue the same pathway.

And for these migrants, the images and news stories aren’t secondhand information that they can question or doubt – images can be interpreted as unchangeable truths.

How migrants get their news

Migrants don’t receive news from New York Times alerts or nightly news.

Their information-sharing largely occurs in an underground informal information exchange that circulates news and stories among migrants heading toward the U.S. through Mexico.

That information is shared, discussed, interpreted and commented on through social media platforms, chat groups and word of mouth. Within 24 hours of the Ciudad Juárez fire, every single social media outlet and migrant chat that I follow as part of my research, comprised of thousands of transit migrants moving throughout Mexico and Guatemala in real time, had posted and reposted the video and news of the incident.

Some comments and replies in social media and chat groups about the incident prayed for mercy and peace for the dead and their loved ones.

Others asked for a list of names of the dead, or about their places of origin, as people desperately sought to find out whether their family members and friends were among the dead and injured. Still others asked for tips and discussed ways to avoid suffering the same fate, such as asking about alternate routes to the border, or sharing ways to avoid ending up in Mexican migrant detention centers.

A shared response

Common among migrants’ reactions to the March 2023 fire was a deep sense of grief. Migrants recognized how close they are to those who lost their lives and expressed a sense of “that could have been me.”

And yet, in my field work, I have found that these horrific events do not deter migrants’ desire to reach the U.S. What they do is reset migrants’ expectations going forward.

Through my field work, I have heard migrants repeatedly tell stories about the dire conditions in detention centers in Mexico.

They report that these poor conditions – rotten food, fleas, lack of clothing or blankets for the cold weather – have triggered hunger strikes and protests.

Broader effects

Another of my main findings is that violent and tragic incidents tend to prompt migrants to avoid any interactions with police or any other officials, even under the guise of help or support.

For example, my research suggests that stories and images of violence like the Ciudad Juárez tragedy will generate a further lack of trust in the Mexican government. I believe that the incident will create certain expectations about the perils of spending time near the border. If they can, I think that migrants will likely avoid Ciudad Juárez and other areas where they feel they may be detained.

I believe the fire will also leave a symbolic scar on migrants in Mexico, who will collectively remember this event and construct their journeys around it.

Angel Alfonso Escamilla García does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Winter storms don’t have to be deadly – here’s how to stay safe before, during and after one hits

Winter storms create many hazards, from slick ice to freezing temperatures. People often underestimate…

Rescheduling marijuana would be a big tax break for legal cannabis businesses – and a quiet form of

Consequences will go far beyond the tax bill that businesses face, a tax law professor explains.

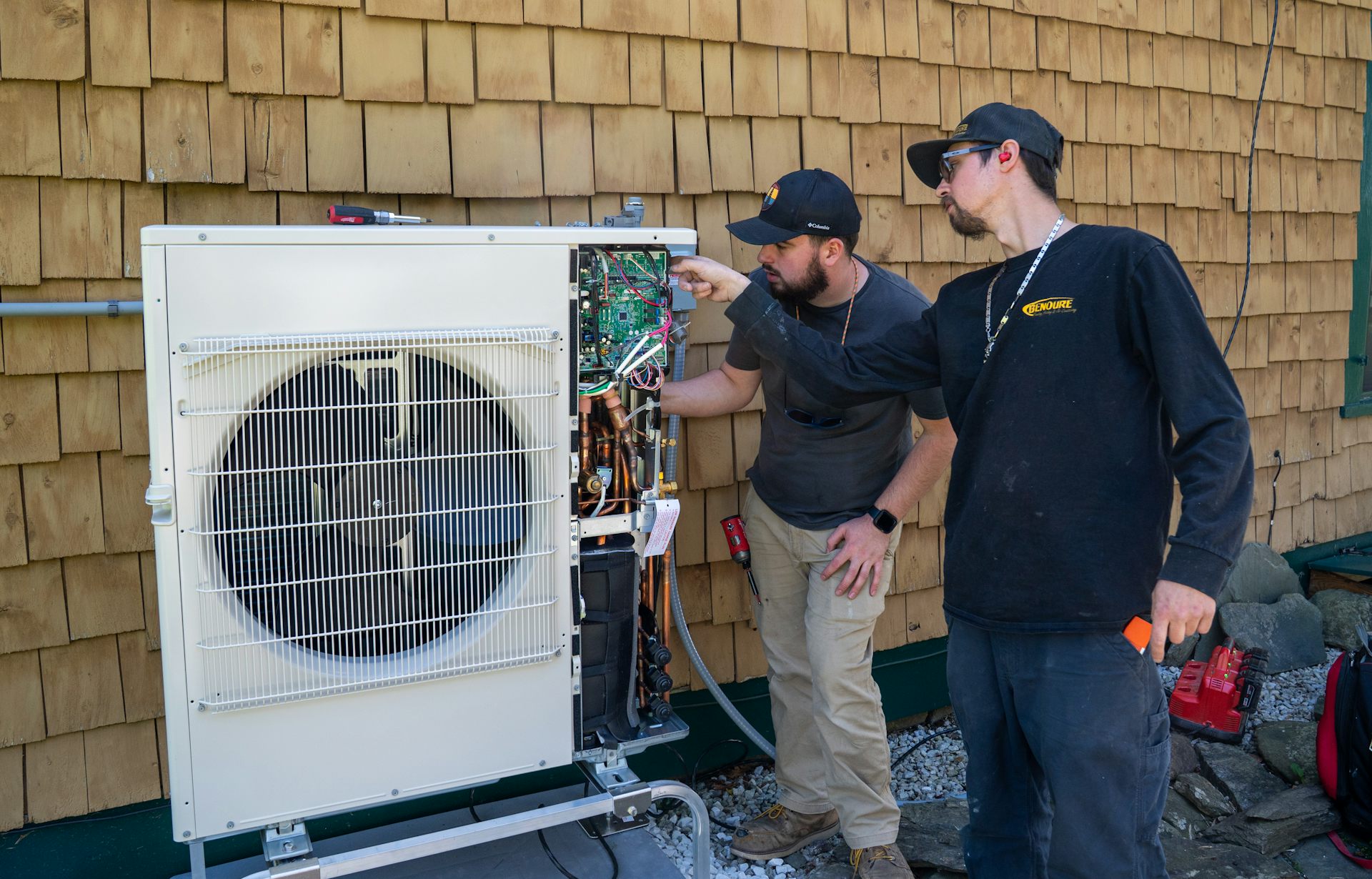

Americans want heat pumps – but high electricity prices may get in the way

Many homeowners could save money on their heating bills by installing heat pumps – but not everyone,…