Environmental justice has the White House's attention, building on 40 years of struggle – but Califo

Poor communities of color have spent decades battling US industrial and agricultural pollution. A new EPA office is designed to support their struggle, but history suggests reason for caution.

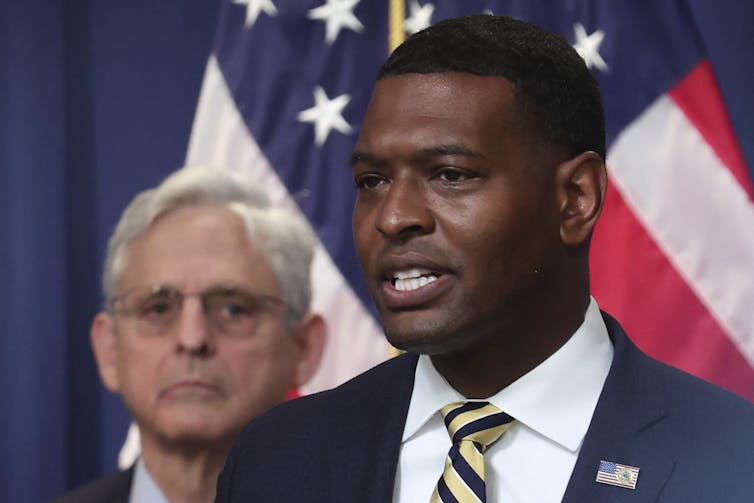

A new office within the Environmental Protection Agency is bringing increased attention to a once-obscure concept: environmental justice.

The Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights will distribute funds designated to help communities that are systematically overexposed to air pollution, contaminated water and other environmental harms. The money – between US$45 billion and $60 billion, depending on whom you ask – was authorized as part of the Inflation Reduction Act enacted in August 2022.

I describe environmental justice as a goal of sustainable, healthy societies in which all people have plentiful access to environmental goods and equitable – but minimal – exposure to environmental risks. The movement coalesced in the late 1970s and the 1980s when working-class and Indigenous communities, along with communities of color, organized across the U.S. against environmental hazards that threatened their health.

My new book, “Evolution of a Movement: Four Decades of Environmental Justice Activism in California,” documents this struggle in California starting in the 1980s. It shows that despite many wins in the state, actual environmental justice remains elusive.

Environmental justice history

One California group that helped build this movement is El Pueblo para el Aire y Agua Limpio, or People for Clean Air and Water.

Based in the small town of Kettleman City in California’s agricultural San Joaquin Valley, El Pueblo’s members were working-class Latinos. From 1988 to 1993, they organized against a proposed hazardous waste incinerator. If constructed, the incinerator – the first of its kind in the nation – would have spewed dioxins and other hazardous chemicals.

El Pueblo staged protests, spoke at public hearings and filed lawsuits to prevent the construction of the incinerator. Eventually, their resistance forced the giant firm Chemical Waste Management Inc. to withdraw its proposal.

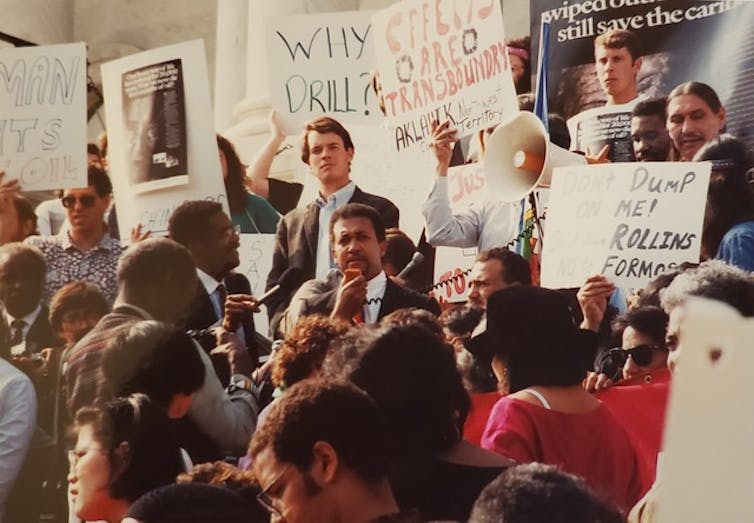

Tiny Kettleman City’s win was hailed as a national victory by other protest groups in similar circumstances. By 1990, these groups came together in a loose national network of people fighting battles to reduce the health risks of toxic exposures in poor communities.

This nascent movement filled a need not well addressed by existing environmental groups. Organizations like the Sierra Club and Environmental Defense Fund were composed of mostly white, middle- and upper-class staff and members.

The exclusionary hiring of such groups followed a long history of racism in the U.S. environmental movement. Some early conservation organizations such as the Save the Redwoods League and the New York Zoological Society – now the Bronx Zoo – had roots in the eugenics movements of the late 1800s and early 1900s, though you won’t see it mentioned on their websites.

As author Miles Powell documents in his 2016 book “Vanishing America,” these early conservationists were motivated in part by a desire to preserve the conditions of the American frontier, where they believed whites had achieved the pinnacle of their innate racial superiority by “taming the wilderness.”

By 1990, formal eugenics policies were largely a thing of the past, but the American environmental movement remained highly segregated.

“The lack of people of color in decision-making positions in your organizations … is also reflective of your histories of racist and exclusionary practices,” wrote 103 activists and community leaders in a 1990 letter to 10 of the nation’s environmental groups.

The next year, the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit brought together some 1,100 people from across the U.S., Chile, Mexico and the Marshall Islands to publicize the concepts of environmental justice and environmental racism.

California as model, California as warning

The movement made early gains in California. There, under grassroots pressure, state legislators started passing environmental justice bills in the early 1990s, though it took years for any governor to sign them into law.

The result is that California today has an array of environmental justice programs. One directs billions of dollars from California’s carbon cap-and-trade program back into marginalized communities.

Accordingly, California is widely seen by activists and policymakers as a model for environmental justice. But, in spite of its many advances, researchers continue to document race-based inequalities in California residents’ exposure to environmental risks and benefits.

For example, despite El Pueblo’s early anti-incinerator victory and other successes, the Spanish-speaking, low-income residents of Kettleman City still breathe in some of the country’s most polluted air and live near the largest hazardous waste landfill in the American West.

Studies show that Californians with contaminated drinking water are disproportionately people of color and the poor. California’s three hazardous waste landfills are located in or near predominantly Latino communities, as are the state’s two waste incinerators.

Activists express frustration with the very policies that are supposed to help them. They argue that some of California’s much-vaunted environmental policies are actually bad for poor people and communities of color.

Indeed, researchers have shown that during the early phase of cap-and-trade, some industrial facilities’ air pollution emissions increased instead of decreasing. These facilities were more likely to be in places that had higher proportions of people of color and the poor than were facilities that reduced their air pollution emissions.

I believe California is better off for its activists’ relentless pursuit of safe, equitable places to live over the past four decades. But the limits of the state’s success show that California should not be seen only as an environmental justice model, but also as a warning of how much more is needed to reverse environmental racism.

The rest of the nation

These lessons apply nationwide.

Recent federal actions under the Biden administration, including a spate of executive orders made early in his presidency, promise historic levels of funding to address environmental inequalities. Yet advocates question whether even the billions of new dollars promised will be enough to rectify the government’s “historic neglect” and active discrimination against the communities nationwide that have forever shouldered the bulk of the country’s environmental hazards.

Activists are also asking questions about how the money will be distributed. Some of these federal funds will be distributed via grant-making or similar mechanisms even though the poorest places may be least well equipped to fight for federal dollars. In California, such processes have put the country’s neediest communities in competition with one another.

And, just as California leaders have taken some actions to slow global warming while simultaneously pursuing others that hasten it, the Inflation Reduction Act moves both toward and away from environmental justice. It includes funds to reduce pollution and slow climate change but, under pressure from Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, it also directs the Department of Interior to go ahead with oil- and gas-drilling lease sales in the Gulf Coast and Alaska that were previously canceled.

Many environmentalists say the bill’s benefits outweigh its negative impacts. A national coalition of environmental justice organizations disagrees. These groups say that, once again, the front-line communities living closest to dirty energy infrastructure are being sacrificed for political expediency.

Environmental racism is deeply entrenched in American society, and will require far-reaching changes to reverse. The Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights has its work cut out for it.

Tracy Perkins currently receives or has previously received research funding from: the University of New Hampshire; University of Maryland, Baltimore County; and University of Arizona; the DC Oral History Collaborative; American Sociological Association; and the University of California. She was a 2014 Duke HASTAC Scholar.

Read These Next

AI’s growing appetite for power is putting Pennsylvania’s aging electricity grid to the test

As AI data centers are added to Pennsylvania’s existing infrastructure, they bring the promise of…

Why US third parties perform best in the Northeast

Many Americans are unhappy with the two major parties but seldom support alternatives. New England is…

Abortion laws show that public policy doesn’t always line up with public opinion

Polls indicate majority support for abortion rights in most states, but laws differ greatly between…