US tragedies from guns have often – but not always – spurred political responses

Congress tends to be most likely to act after an assassination or assassination attempt of historic proportions or mass shootings. But sometimes lawmakers do nothing beyond debate new measures.

The nationwide call for stronger gun laws in the aftermath of mass shootings in Buffalo, Uvalde and the over 200 other places where such tragedies took place so far in 2022 is understandable.

It’s also predictable. Whether efforts to pass new federal or state laws to raise the minimum age for buying semiautomatic rifles, expand background checks and similar measures succeed or fail this time, they will follow a pattern in American politics that traces back more than a century.

As I explain in my book “The Politics of Gun Control,” efforts to restrict and regulate firearms have followed the assassination of political leaders, crime waves and mass shootings since before World War I.

A spate of shootings in 1910-1911

In 1910, New York City Mayor William J. Gaynor boarded the steamship Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, moored at the dock in Hoboken, New Jersey. He was embarking on a monthlong European vacation.

The trip was interrupted when a disgruntled former city employee shot him in the neck with a concealed pistol. Gaynor, seriously wounded in the assassination attempt, died in 1913.

The incident heightened already growing calls for a new handgun law in New York state amid rising gun violence, especially in New York City.

In 1911, the noted novelist David Graham Phillips was shot in Manhattan by a man who turned his gun on himself. Both died.

With the city coroner’s office reporting a sharp increase in gun homicides, New York state lawmakers responded by enacting a law requiring permits to buy, own and carry handguns. Other states enacted similar pistol permit laws.

The U.S. Supreme Court will soon rule on whether that 1911 measure violates the Second Amendment.

Prohibition-era tumult

Gangland violence tied to alcohol trafficking during Prohibition flared throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. This mayhem led to many new laws restricting gun ownership.

Most states banned the fully automatic weapons gangsters favored. At least eight enacted laws restricting or barring semi-automatic firearms too.

In 1933, shortly before his first presidential inauguration, Franklin D. Roosevelt narrowly escaped an assassin’s bullet. A year later, Congress passed the National Firearms Act of 1934. This first significant federal gun law required that those wanting to own the listed weapons be registered with the Treasury Department, fingerprinted and subject to a background check, plus pay a substantial fee to own fully automatic firearms, sawed-off shotguns, silencers and similar weapons.

One month before FDR signed that measure, Texas police gunned down the infamous gangster duo Bonnie Parker and Clyde Champion Barrow. And the FBI killed John Dillinger, another notorious outlaw, a month later.

Assassinations and upheaval in the 1960s

President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 led Congress to consider new gun measures. Lawmakers held hearings, but those efforts languished until the assassinations of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy in 1968.

Rising crime rates and unrest in cities like Detroit, Los Angeles, Chicago and Washington also increased the public’s safety concerns.

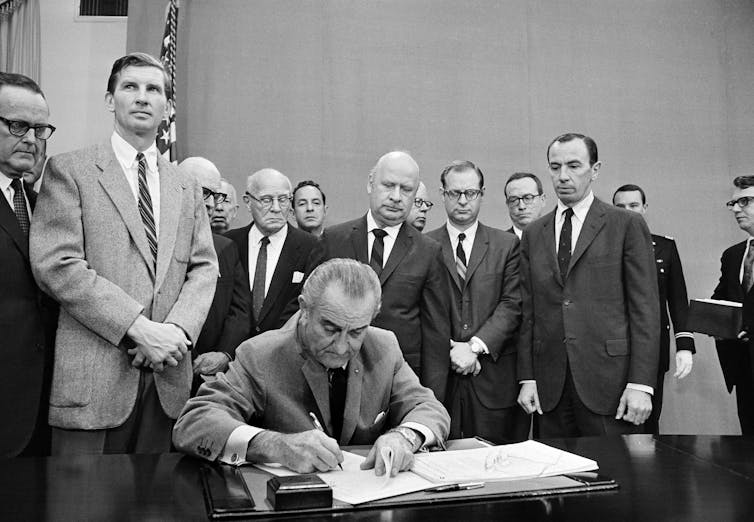

Congress responded by passing the Gun Control Act of 1968, which President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law.

It restricted interstate gun shipment, barred gun sales to minors, felons and people deemed “mentally defective,” and strengthened licensing and record-keeping, among other measures.

The first modern gun control groups devoted exclusively to advocating for stronger regulations arose in the 1970s. Chief among them were Handgun Control, Inc. and the National Coalition to Ban Handguns, later renamed the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence. Both were formed in 1974.

Aftermath of Reagan assassination attempt

The foiled 1981 assassination attempt against Ronald Reagan left James Brady, his press secretary, disabled. Brady and his wife, Sarah, joined Handgun Control, Inc., an advocacy group later renamed the Brady Campaign. Their organization spearheaded the successful effort to enact a new federal law named after Brady requiring background checks before most purchases of new guns.

In 1989, a man using an AK-47 assault rifle shot and killed five children and wounded 29 others at an elementary school in Stockton, California. That same year, California became the first state to ban semi-automatic assault weapons – military-style weapons designed to fire a round with each pull of the trigger.

After a multi-year effort, Congress finally enacted a 10-year federal ban on assault weapons in 1994. The law also limited ammunition magazines to those holding no more than 10 rounds – excluding those previously manufactured.

The law expired in 2004, after which mass shootings became more frequent, with assault weapons increasingly used by mass shooters. Repeated efforts to renew the ban have failed.

The gun control movement pressed to further strengthen gun regulations. Those efforts culminated in the passage of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act in 1993, which amended the 1968 gun-control law by establishing a national system of background checks and a five-day waiting period for handgun purchases.

The law called for eliminating that waiting period in 1998, replacing it with an instant background check system.

Congress balks

In the aftermath of the April 1999 Columbine High School shooting, where two heavily armed students killed 12 of their peers and one teacher, and wounded 23 others in Littleton, Colorado, Congress considered several new gun measures.

The Senate narrowly passed a bill in 1999 to establish uniform background checks for all gun purchases, tougher penalties for juvenile gun offenders and requiring locking devices to be sold with new handgun purchases.

The more conservative House of Representatives defeated a much weaker gun bill due to opposition from both lawmakers who wanted a stronger bill and others who opposed gun-control legislation of any kind.

The National Rifle Association, formed in 1871 to improve the shooting and marksmanship skills of military-age men, was by this time the primary organization devoted to thwarting gun laws.

The NRA’s heavy lobbying contributed to that defeat.

Bloodshed in Connecticut, Florida and beyond

The 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, where 20 children and six staff members were killed, spurred President Barack Obama and many lawmakers to seek to tighten gun regulations.

The Senate in early 2013 considered measures to ban assault weapons, limit high-capacity ammunition magazines, require more background checks and improve record-keeping. Senators also considered several provisions to ease gun ownership restrictions by scaling back the background check waiting period, easing regulations on interstate weapons transport and handgun sales, and even a provision to make the use of gun records for creating a registry a felony.

All failed in the Senate. The House, likewise, didn’t pass any new gun-related legislation

Yet the Sandy Hook shooting mobilized three new nationwide gun groups: Everytown for Gun Safety, founded by former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, Americans for Responsible Solutions, formed by former Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, who had been seriously wounded in a 2011 mass shooting, and her husband, Mark Kelly, who is now serving in the Senate, and Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America.

In 2016, the Giffords-Kelly organization combined with another gun safety group to become the Giffords organization. The Moms Demand Action became part of Everytown in 2014.

After Parkland

In 2018, a disgruntled student entered Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, armed with with an assault-style weapon. He killed 17 people and wounded 17 more.

Parkland students spearheaded their own nationwide gun safety effort under the “#NeverAgain” banner. Its “March For Our lives” demonstrations mobilized thousands of students across the country, as did the organization Students Demand Action, which went nationwide in 2018 and is affiliated with Everytown.

That year, 27 states, including Florida, enacted over 60 new gun regulations.

Still, Congress failed to act with the exception of passage of the modest Fix NICS Act. Passed with bipartisan support in 2018, the law improves data-gathering and reporting to the National Instant Criminal Background Check System for those seeking to buy guns. The NRA didn’t oppose the measure.

As this history attests, predicting the likelihood of congressional action now or in the near future is anyone’s guess.

Robert Spitzer is a member of the National Rifle Association and the Giffords organization.

Read These Next

Why US third parties perform best in the Northeast

Many Americans are unhappy with the two major parties but seldom support alternatives. New England is…

Abortion laws show that public policy doesn’t always line up with public opinion

Polls indicate majority support for abortion rights in most states, but laws differ greatly between…

Detroit was once home to 18 Black-led hospitals – here’s how to understand their rise and fall

In the early 20th century, Detroit’s Black medical professionals created a network of health care…