Putin's control over Ukraine war news is not total - it's challenged by online news and risk-taking

Russia is cracking down on freedom of speech and media. But other factors, like outside online information, could make it difficult to control war propaganda - and block out other information.

The Russian media is a powerful propaganda machine. Russian media outlets have been closely controlled by the government over the past several decades, and since Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022, many journalists and editors have been turned into mere mouthpieces for the government line.

But a few recent examples of journalistic defiance show that the Kremlin can’t guarantee full control over Russian journalists during the war. At the same time, Russians’ access to online information about the war constantly challenges the Kremlin’s lies about the invasion.

Some Russian journalists have left the country since the end of February, while others have resigned from their jobs.

“For the most part, even the state media employ people with normal moral standards. Most of them are not all in with what’s happening now - all this hell and horror,” said commercial television NTV anchor Lilia Gildeeva, who resigned over the invasion and has left Russia.

For now, most Russian journalists, many apparently driven by fear of arrest or worse, are publicly going along with President Vladimir Putin’s lies about the war. And it’s certainly not clear if the exodus of individual journalists will result in systematic change in Russia.

But even in authoritarian states, journalists can have power.

I believe that if enough journalists take a serious risk and reject the Kremlin’s control, they can significantly undermine Russia’s war on Ukraine by telling the public the true story of what is happening. I base this on 30 years of studying the Russian media, from how state control of media destroyed nascent political parties to the way the internet challenges Kremlin control.

‘Stop the war’

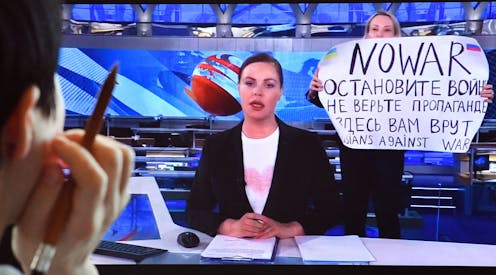

Russian television news editor Marina Ovsyannikova walked on the news set of state-run First Channel on March 14, 2022, and held up a sign behind the newscaster that said “no war” in English and “stop the war, don’t believe the propaganda” in Russian. Her unprecedented protest was cut off in seconds, but it illuminated a crack in the facade of the state-aligned Russian media.

Since the invasion, Russia has enacted new laws that make saying there is a “war” or “invasion” in Ukraine a crime punishable by up to 15 years in prison. The law applies to all journalists, no matter whether they work for state or commercial news outlets. Indeed, the Kremlin controls all major media outlets whether they are owned by the state or commercial enterprises.

During the first week of March alone, Russia blocked approximately 30 Russian and Ukrainian independent media sites.

So far, Russian media are mostly toeing the Kremlin line. For example, Russian television features a constant barrage of brave Russian soldiers, grateful Ukrainians and citizens demonstrating their support for Mother Russia. Scenes of destruction and desperation in Ukraine are blamed on Ukrainian forces.

While Putin relies heavily on Russian journalists to disseminate lies – that Ukraine is committing genocide, for example – and to justify the war, he cannot control the first livestreamed war. Citizens can still post videos online that are viewed by millions despite the Russian government blocking many internet platforms, including Facebook and Twitter, since the invasion.

Unless Putin is able to enforce a ban on virtually all of the internet, digital-savvy Russians will continue to find ways to share information through virtual private networks and the Tor browser, which allow users to bypass government restrictions.

TV becoming less popular

Research by the Yuri Levada Analytical Center, a Moscow-based independent survey organization, shows television is a fading force in Russia.

While 88% of Russians used TV as their primary news source in 2013, this dropped to 62% in 2021, according to the Center. During the same time period, the percentage of Russians using social media as their primary source for news rose from 14% to 37%.

The difference across generations is stark: While 86% of Russians aged 55 or older were turning to television for news in 2021, only 44% of those aged 18-24 were doing the same.

Russian television has high production values, with news and political talk shows that would look familiar worldwide. News content, however, is purely authoritarian: Forces friendly to the Kremlin are praised, enemies are vilified, and inconvenient facts are ignored or twisted.

Russian television, for example, has falsely reported that American agents “seek to deploy anti-Russian bioweapons” and “Ukraine’s leaders are hellbent on acquiring nuclear weapons” to attack Russia.

Disinformation does not necessarily turn viewers away, particularly in a country in which distrust of the West in general and America in particular runs high.

Focus groups in Russia show that people - especially older viewers - often seek reassurance and patriotism, rather than objective information, from TV. Those who seek more factual information are likely to go online.

Russia cracking down on media

Journalists in Russia have sometimes challenged the regime to a degree, reporting the truth about situations ranging from rigged elections to the war in Chechnya.

Since Putin took office, all Russian journalists have faced increased restrictions, including arrest, attacks and murder of those who directly challenge the Kremlin. At least 58 Russian journalists have been killed since 1992, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Two of the remaining voices of independent journalism fell silent in early March 2022. The Echo of Moscow radio station and Dozhd TV, known as Rain, went off air after Russian authorities blocked access to their websites.

Other outlets have chosen to self-censor, while many journalists have fled the country.

There are other signs that the Kremlin’s hold over the media is loosening, as several high-profile Russian journalists have resigned since the invasion, including veteran reporters and prominent broadcasters.

These journalists have fallen silent and have no options for working in Russia, but their refusal to go along with the heightened propaganda regime shows that Putin’s control over journalists is not absolute.

Ukraine war propaganda

Ovsyannikova’s protest on TV was a single event. A Russian court fined her US$215 for violating protest laws, and she is at further risk, having been accused of being a British spy.

Even some who have produced state propaganda for years think war propaganda about Ukraine has gone too far, as Ovsyannikova said she did. Other journalists who have been loyal to the Kremlin for years or even decades may now also be questioning their roles.

This means the Kremlin is fighting a war for media control on two fronts.

When loyal journalists won’t fall in line, or even choose to speak out against the war, it could have a significant effect on the Russian audience that closely follows television.

At the same time, the Kremlin can’t stop the inevitable spread of online content that shows what’s really going on in Ukraine.

[The Conversation’s Politics + Society editors pick need-to-know stories. Sign up for Politics Weekly.]

Sarah Oates has received funding from the Economic and Social Research Council in the United Kingdom, the British Academy, and the Leverhulme Trust to study Russian television.

Read These Next

Jesse Jackson’s misdiagnosis of Parkinson’s is common – new genetic discovery could lead to treatmen

People typically die from progressive supranuclear palsy within 7 to 10 years. There is currently no…

As the Oscars approach, Hollywood grapples with AI’s growing influence on filmmaking

AI tools can now generate movie scenes, resurrect lost footage and replace entry-level jobs – forcing…

When US fights in the Middle East, American Muslim students often face discrimination

The war on terror is among the Middle East conflicts that sparked a rise of anti-Muslim and anti-Arab…