Texas voting law builds on long legacy of racism from GOP leaders

For much of the country’s history, the Republican Party was the party of Lincoln and racial equality, and the Democratic Party backed Jim Crow laws and white supremacy. The two parties switched.

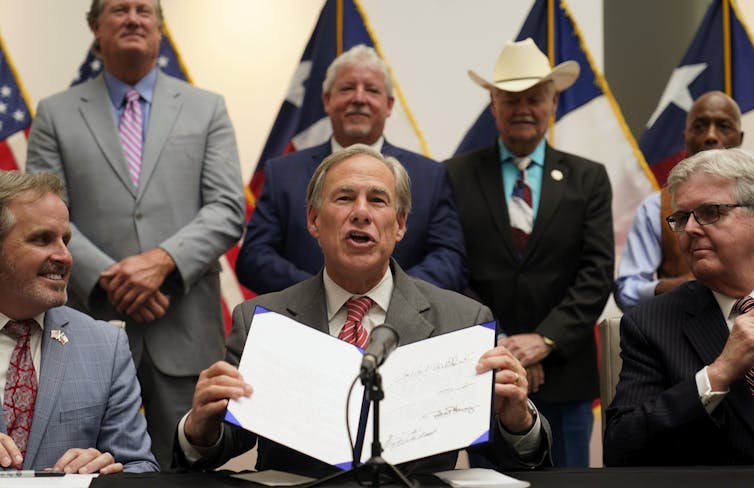

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signed into law a bill on Sept. 7, 2021, that reduces opportunities for people to vote, allows partisan poll watchers more access and creates steeper penalties for violating voting laws.

The Republican governor argued that the legislation would “solidify trust and confidence in the outcome of our elections by making it easier to vote and harder to cheat.” Democratic opponents of the measure, however, said Republican legislators presented no evidence of widespread voter fraud during debate on the bill.

Civil rights organizations immediately filed suit, calling the law unconstitutional because it is intended to restrict voting among minorities, who overwhelmingly support Democratic political candidates.

Across the country, Republicans have turned to gerrymandering and voter suppression legislation such as closing polling stations in minority and low-income precincts, mandating discriminatory voter ID laws and purging millions from voter rolls. In addition, GOP politicians and right-wing commentators have demanded that educators quit teaching the facts of America’s racist history.

For several decades, the GOP has depended on racism to keep white people in power and nonwhites on the outside.

Lee Atwater and the strategy of racism

In 1981, longtime GOP strategist Lee Atwater plainly declared that the Republican Party’s key strategy was racism. Atwater described how the GOP began to define itself as a white supremacist party in response to the civil rights movement. The Nation magazine later published the full audio recording of the interview.

“You start out in 1954 by saying, ‘N—–, n—–, n—–.’”, Atwater said, using the actual racial slur.

“By 1968, you can’t say ‘n—–’ – that hurts, backfires. So you say stuff like, uh, ‘forced busing,’ ‘states’ rights,’ and all that stuff, and you’re getting so abstract,” he continued.

“Now, you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things, and a byproduct of them is, Blacks get hurt worse than whites,” Atwater explained. “‘We want to cut this’ is much more abstract than even the busing thing, uh, and a hell of a lot more abstract than ‘N—–, n—–.’”

The GOP moves from overt racist words to coded words

For much of the country’s history, the Republican Party was the party of Abraham Lincoln and racial equality, and the Democratic Party was the party of Jim Crow laws and white supremacy. The two parties switched positions during the civil rights movement when the Democrats abandoned their support for segregation and Republicans sought to appeal to segregationists.

In the early 1960s, U.S. Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona, a Republican, challenged the GOP’s more liberal politicians to redefine the Republican Party as what newspaper editor William Loeb called “the white man’s party.” Republican New York Gov. Nelson B. Rockefeller responded that if the GOP embraced Goldwater, an opponent of civil rights legislation, as its presidential candidate in 1964, then it would advance a “program based on racism and sectionalism.”

Goldwater won the GOP’s nomination but lost the presidential election in a landslide to the Democratic incumbent, Lyndon Johnson. But even without winning the Oval Office, Goldwater and other like-minded conservative Republicans won the hearts and minds of pro-segregation Democrats, who were angry with Johnson for signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The GOP, as Atwater pointed out, learned to use coded words to court these disillusioned Democrats who became Republicans in what would become known as the “great white switch” or Southern strategy.

States’ rights, welfare queens and Willie Horton

Republican Richard Nixon won the 1968 presidential election in part by using references to states’ rights and “law and order,” rather than by making blatant appeals to white supremacy or racism. Nixon’s chief of staff, H.R. Haldeman, noted that Nixon “emphasized that you have to face the fact that the whole problem is really the Blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognized this while not appearing to.”

In 1980, former California Gov. Ronald Reagan, also a Republican, gave a presidential campaign speech at the Neshoba County Fair near Philadelphia, Mississippi, where three civil rights workers had been murdered in 1963. Reagan declared his own support for states’ rights. Gabrielle Bruney wrote in Esquire that “by touting himself as a states’ rights candidate near the site of one of the nation’s most famous hate crimes, Reagan offered voters a racism that was both obvious and unspoken.”

As president, Reagan used coded rhetoric to connect race to crime, welfare and government spending. For instance, Bryce Covert wrote in The New Republic, Reagan frequently used distortion in his references to a single con artist named Linda Taylor, the so-called “welfare queen,” to argue that welfare was corrupt and Black people were too lazy to work.

Atwater worked as a consultant for Reagan and then as campaign manager for Vice President George H.W. Bush’s presidential campaign in 1988. Atwater approved a television ad blaming Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis, the former governor of Massachusetts, for a furlough program in the state that released a Black first-degree murderer, Willie Horton, who then raped a white woman. Atwater famously claimed, “By the time we’re finished, they’re going to wonder whether Willie Horton is Dukakis’ running mate.” Bush won the election.

Onward to Donald Trump

The GOP’s hold on the South became complete in 2016 when Donald Trump won all the former Confederate states except Virginia.

Trump became one of the GOP’s top contenders for the 2012 presidential nomination after questioning without evidence whether Black president Barack Obama was born in Hawaii. When Obama released his birth certificate, Trump’s candidacy fell apart.

When Trump ran for president in 2016, he used racially divisive rhetoric, calling Mexican immigrants criminals and rapists, proposing a ban on all Muslims entering the U.S. and suggesting a judge should recuse himself from a case solely because of the judge’s Mexican heritage.

His campaign used the slogan “Make America Great Again,” which had been widely criticized for being a dog whistle to white people who felt that minorities were encroaching on their country. Then, as president, he pandered to white supremacists by refusing to criticize them and by using coded words. He told Americans that there are “fine people on both sides” after a confrontation between white supremacists and counterprotesters in Charlottesville, Virginia, on Aug. 12, 2017.

When Trump ran for reelection in 2020, he renewed his birther claim by insinuating that Democratic vice presidential candidate Sen. Kamala Harris, who is Black and Asian, “doesn’t meet the requirements” to run for vice president. When Trump lost the election, he challenged the accuracy of voting in precincts that were heavily minority.

Now Republicans in Texas and around the nation are back to openly expressing their racism with no need for dog whistling or other forms of abstraction.

[Understand key political developments, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s politics newsletter.]

Chris Lamb does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

How the Emerald Isle shaped the Steel City – Pittsburgh’s rich Irish history

Long before Pittsburgh’s modern Irish celebrations existed, Irish immigrants helped shape the city…

When US fights in the Middle East, American Muslim students often face discrimination

The war on terror is among the Middle East conflicts that sparked a rise of anti-Muslim and anti-Arab…

While the US government is investigating unidentified anomalous phenomena, academic researchers stud

Surveys have found that researchers studying UAPs can face pushback from mentors and colleagues, even…