From the labor struggles of the 1930s to the racial reckoning of the 2020s, the Highlander school ha

The training center, which welcomed Rosa Parks and John Lewis before they became famous, still empowers and inspires marginalized Americans to use their own voices and talents.

During this period of racial reckoning, many Americans are seeking to make the United States more equitable and just. Many new organizations and coalitions are arising out of a new wave of engagement, but they don’t need to start from scratch.

The Highlander Research and Education Center, a training ground for civil rights activists founded nearly 90 years ago, offers a useful model. As a social movement historian, I am intimately familiar with how this school and similar engines of grassroots engagement have transformed America’s social and political landscape by inspiring generations of leaders seeking to end institutional racism.

Located outside of Knoxville in the eastern Tennessee mountains, Highlander is among the hundreds of organizations that the billionaire philanthropist and author MacKenzie Scott has funded to combat systemic inequity. It’s also playing a critical role in attracting and distributing philanthropic support to lesser-known Southern grassroots organizations.

Together with Southerners on New Ground, another activist training group, it helped launch the Southern Power Fund in 2020. The initiative had raised US$14 million by mid-2021 to make it easier for grassroots organizations to address local needs with no-strings-attached grants.

Myles Horton vs. the color line

Highlander was the brainchild of Myles Horton, a white Southerner who grew up under the crushing weight of poverty in rural Tennessee in the early 20th century. As his parents scratched out a living doing odd jobs, Horton grew increasingly bitter regarding the social and economic system that produced such stark contrasts between the privileged few and the struggling masses. He also became an avid reader.

During the Great Depression, Horton went to graduate school at Union Theological Seminary in New York and the University of Chicago.

There, he was mentored by John Dewey, a philosopher who believed in the need for education aimed at “correcting unfair privilege and unfair deprivation.” American social movements at that time, when the nation’s economic and racial divisions were becoming deeper, were intensifying their critiques concerning the wealth gap and the color line that violently threatened and undermined the lives of millions of African Americans.

Subsequently, Horton founded the Highlander Folk School in 1932. Nestled in the tiny backwoods town of Monteagle, Tennessee, it aimed “to educate rural and industrial leaders for a new social order.”

For Horton, the economic crisis was the perfect moment to achieve the unthinkable: bridging the color line to create synergy between Black and white Southerners. Within Highlander’s welcoming walls and in its outdoor classes, segregation or any pretense of hierarchy was nonexistent.

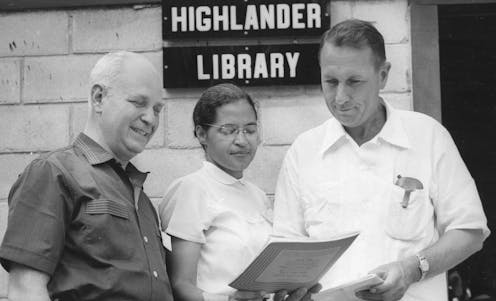

Groups of Southern labor organizers and civil rights activists would gather at Highlander to read and discuss. Its library was stocked with books by progressive intellectuals, including not just Dewey but the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr and the educator and activist George S. Counts.

Participants would learn even more from their community-building. Horton sought to create a space where people of all backgrounds could be exposed to history and literature that enlightened them about their common struggles. Highlander also fostered the creation of music and art that built communion and solidarity, while inculcating the radical notion among trainees that they could transcend racial and class divisions.

In sharing a common space for an extended period, participants in Highlander’s training program could begin to build a truly democratic society as a “circle of learners.”

Empowering civil rights leaders

Today’s training center is the successor to Horton’s original civil rights movement incubator. In 1957, Martin Luther King Jr. praised Highlander’s “noble purpose and creative work” with having “given the South some of its most responsible leaders.”

Four months before her historic act of dissent against Montgomery’s segregated buses, for example, Rosa Parks attended a Highlander workshop on one of several trips she would make there.

And as student sit-ins rocked America’s social and political foundations in the spring of 1960, it was Highlander that served as a retreat for many of the Nashville students, including John Lewis, the future congressman.

Because of unrelenting attacks by prejudiced politicians who alleged that Highlander was spreading communism, Tennessee authorities forced the school’s closure and revoked its charter in 1961. The staff then reincorporated as the Highlander Research and Education Center and moved, first to Knoxville and then to New Market, a small town about 25 miles away.

Under its barely changed name, the nonprofit school would keep forging some of the most unlikely coalitions at the height of the Jim Crow South and beyond.

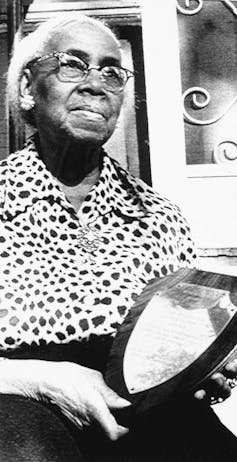

Septima Clark

One of Horton’s most influential hires was a South Carolina schoolteacher named Septima Clark. A graduate of two historically Black colleges, she first arrived in 1954 out of curiosity because she wanted to see for herself the one place she had heard of where “blacks and whites could meet together and talk over the problems” that defined the Jim Crow South.

She returned a year later after being fired from her teaching job in Charleston for belonging to the NAACP. At Highlander, Clark developed and led workshops on leadership. Parks was among her first students, six months before an eventful act of dissent aboard a bus in Montgomery.

Clark became a full-time staffer in 1956. She later implemented her Highlander lesson plans in what she referred to as Citizenship Schools in Johns Island, South Carolina.

Horton’s and Clark’s methods of empowering and training local folks in political literacy became staples of organizations such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC.

SNCC later emulated the concept of Clark’s Citizenship Schools during the Freedom Summer campaign of 1964, which sought to register scores of Black voters who had been barred from registering in Mississippi – under the threat of white terrorism as well as Jim Crow laws.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter.]

SNCC activists also created Freedom Schools throughout the Mississippi Delta region that exposed Black residents to an education that most had been deprived of as impoverished sharecroppers.

Building new coalitions

After the school’s organizers relocated, twice under its new name, Highlander redoubled its efforts to address systemic poverty. In recent years, while upholding its original mission, Highlander has begun to tackle issues such as environmental racism, xenophobia and human rights abuses while advocating for intergenerational and multicultural coalition-building.

Tragically, there are those who still regard such efforts as a threat.

The Highlander Research and Education Center’s main office building in New Market, Tennessee, burned down in 2019. The subsequent identification of a white power symbol raised suspicions of arson, but the case apparently remains under investigation.

Although the blaze engulfed the building, it didn’t raze the spirit and mission of the center that in my view has served as a citadel for democracy and justice.

Jelani M. Favors does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Clarence ‘Taffy’ Abel: A pioneering US Olympic hockey star who hid his Indigenous identity to play i

Despite being a foundational figure in American hockey, Taffy Abel – who hid his Ojibwe heritage so…

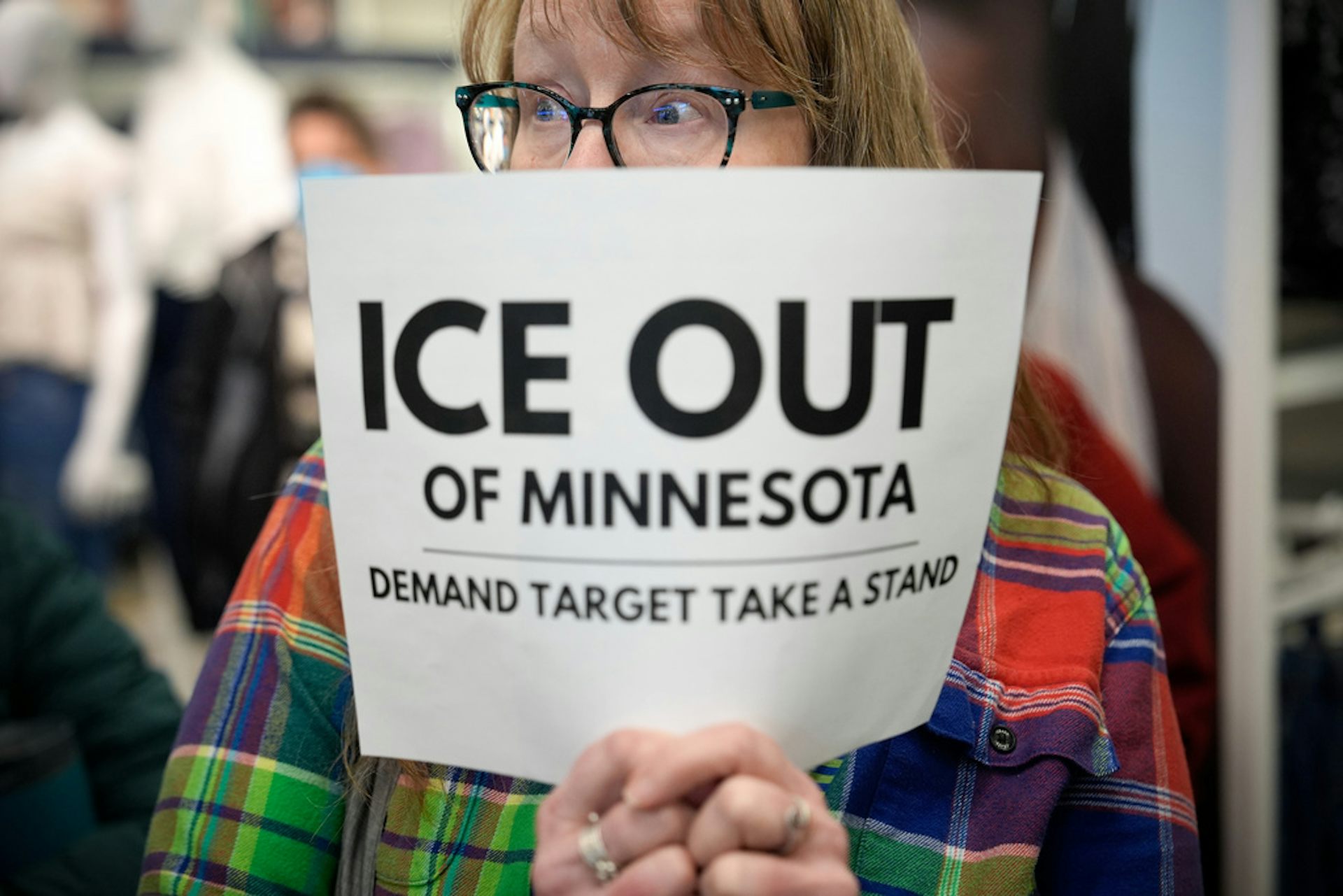

Why corporate America is mostly staying quiet as federal immigration agents show up at its doors

Federal immigration raids in Minnesota prompted a social backlash. But the business community is largely…

ICE and Border Patrol in Minnesota − accused of violating 1st, 2nd, 4th and 10th amendment rights −

In Minnesota, can constitutional protections withstand the actions of a federal government seemingly…