Faces of those America is leaving behind in Afghanistan

As American troops leave Afghanistan, a scholar of the country's history and culture reexamines his photos of the nation's people.

U.S. troops are already heading home from Afghanistan, ending a two-decade-long war that saw as many as 100,000 American troops there. The withdrawal of the remaining few thousand is slated to be complete by the symbolic date of Sept. 11, 2021.

I know this land well from my journeys across more than half of its provinces as a professor of Afghan history and as a former employee of the CIA’s Counter-Terrorism Center tracking the movement of Taliban and al-Qaida suicide bombers. I also advised the military on Afghan terrain, tribes, politics and history.

While on my solo missions for the CIA and U.S. Army beyond the safety of our base’s walls, in what my team described as the “red zone,” I also did something that none of my U.S. Army comrades – who traveled in convoys and were restricted by formal rules of engagement – could do. I freely photographed the fascinating Afghan people around me as they went about their lives in an active war zone.

Lately, I worry about the fate of the people in these photos and others I have taken. Their world may be destroyed if, or when, the fast-advancing Taliban reconquer the last remaining government-controlled zones.

These images show glimpses of the potentially doomed people and ways of life the U.S. is leaving behind as the troops depart.

The warlord

In this photograph from 2003, General Abdul Rashid Dostum, an Uzbek Mongol cavalry commander, rides his prized war stallion Surkun.

Dostum, a legendary military leader who fought alongside the Soviets in the 1980s to extend modernity to Afghanistan and has faced accusations of war crimes against the Taliban which he denies, is a friend and the focus of my 2013 book, “The Last Warlord: The Afghan Warrior who Led US Special Forces to Topple the Taliban Regime.” In 2001 he rode Surkun into combat alongside horse-mounted U.S. Special Forces Green Berets to overthrow his northern Turkic-Mongol people’s historic foes, the ethnic Aryan Pashtun Taliban regime.

Hundreds of his riders were killed in the desperate mountain campaign against their Taliban enemies, as seen in the 2019 Hollywood blockbuster “12 Strong: The True, Declassified Story of the Horse Soldiers of Afghanistan,” which was in part based on my book.

The girl

This cherubic nine-year-old girl at left was charged with babysitting her little brother while her parents worked in the fields in a remote desert region. I have no idea what her fate was, but many impoverished girls like her do not get the opportunity to get an education and are married off in arranged marriages when they are young.

The hosts

I was always amazed at the warm welcomes I received while traveling among the Uzbek-Mongol, Persian-Tajik and Hazara-Shiite Mongol tribes of northern Afghanistan, who are closely allied with the U.S. I was regularly invited into their simple homes, where my hosts would eagerly offer me lamb or goat, often after slaughtering their only source of meat for an honored guest.

The chicken fighters

On most Friday afternoons during my time in Kabul, there were chicken fights, like this one in the Garden of Babur, a popular park built around the marble grave of Babur, the founder of India’s magnificent Moghul Empire. At the fights, men bet on which chicken would win, but the pastime was banned by the Taliban as “un-Islamic” as all such “sinful” games distracted from the worship of God.

The schoolgirls

After five years of being denied the right to an education by the Taliban, these middle school girls in the town of Sheberghan in 2005 were excited to return to school. One girl, third from the right, was crying: She had just told me the story of how the Taliban had killed her parents.

She fretted, “The day the Americans leave the Taliban will return and execute us girls if we try to learn to read and write, which is forbidden for females by their law.”

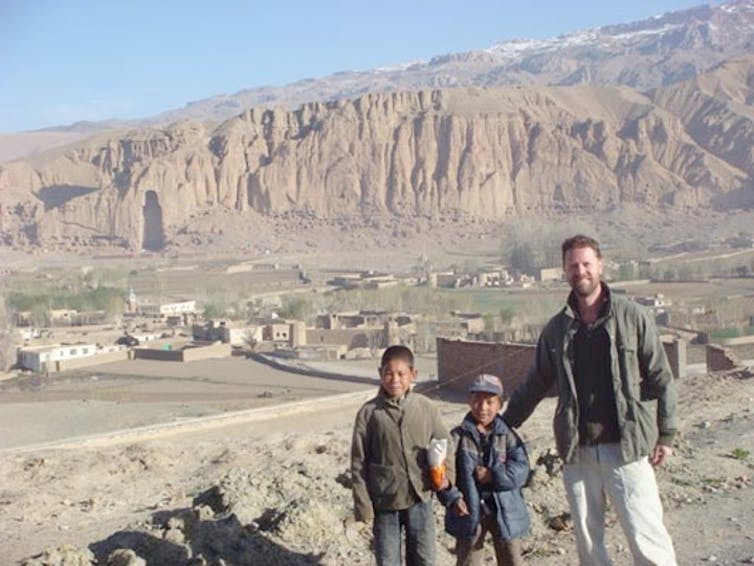

The guardians of the Buddhas

In the idyllic Vale of Bamiyan, at 8,000 feet above sea level in the remote Hindu Kush mountains, the Hazara Mongols for centuries cherished two massive statues of the Buddha, carved into the cliffs in the sixth century. In 2001, the Sunni Taliban destroyed the statues, defying international outcry, in a direct insult to the repressed Shiite Hazaras.

The nomads

As I traversed the soaring mountains and vast deserts of this ancient land that time seemingly forgot, I frequently encountered welcoming and curious Aryan Pashtun nomads known as Kuchis. These wanderers invariably invited me to join them for a simple meal in exchange for my stories about a different world known as America, a land that these humble people, who live out their entire lives in tents without electricity, could not imagine.

The burger and pizza chef

An Afghan who worked on a U.S. base and came to love all things American opened this pizza and burger restaurant in Kabul which, like many businesses, featured an armed guard out front. Other American-style restaurants opened up after the Taliban were driven from Kabul, including the remarkably delicious KFC – Kabul Fried Chicken.

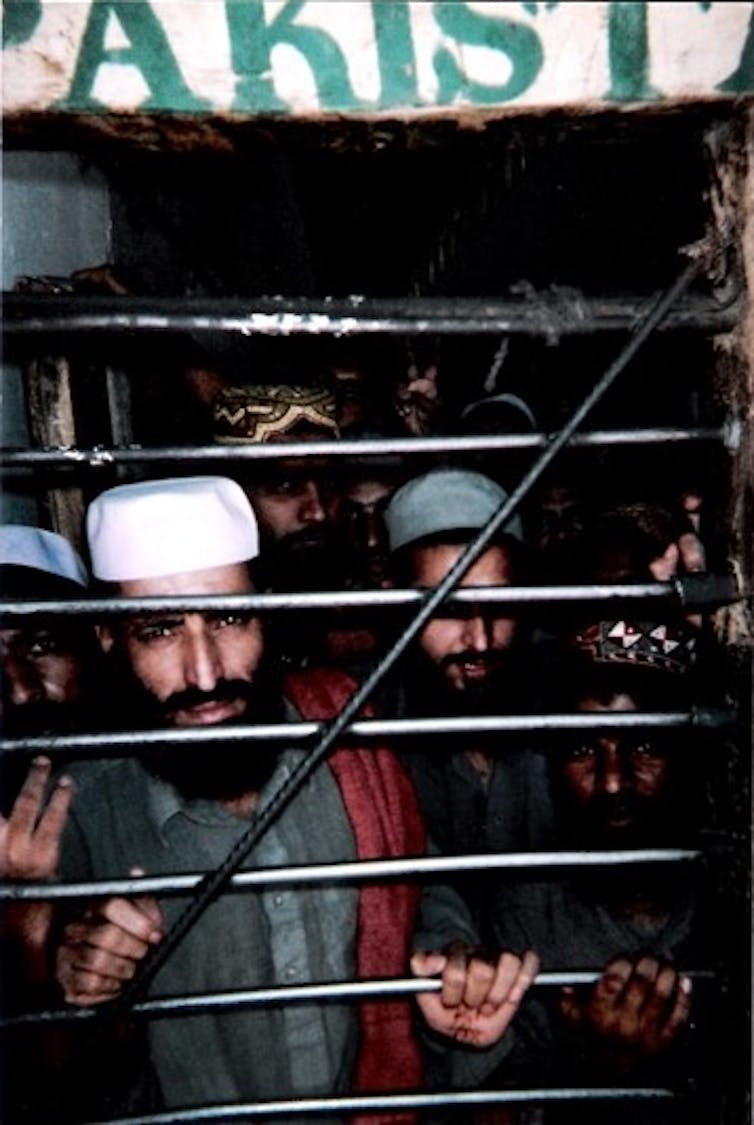

The Taliban

I interviewed several dozen Taliban members, who had been captured by General Dostum’s forces, in a fortress-like prison in the northern deserts of Afghanistan. One of the captives told me a common Taliban mantra: “You Americans may have the watches, but we have the time… We will outlast you.”

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Brian Glyn Williams does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

When US fights in the Middle East, American Muslim students often face discrimination

The war on terror is among the Middle East conflicts that sparked a rise of anti-Muslim and anti-Arab…

In its hunt for critical minerals, the US is misconstruing what is and is not America’s

There’s a growing interest in mining the ocean seabed for minerals essential to technology. But whose…

Nearly 1 in 3 missing children in the US are Black, driving Pennsylvania and other states to propose

Black children who go missing are often labeled as runaways, which excludes them from the Amber Alert…