What happened to Confederate money after the Civil War?

Confederate paper money was a promise to exchange the bill for gold or silver, but only after the Confederacy won the war.

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

What happened to Confederate money after the Civil War? – Ray G., 12, Arlington, Virginia

At the time the Civil War began in 1861, the United States government did not print paper money; it only minted coins. As a historian of the American Civil War, I study how the Confederate government used a radical idea: printing paper money.

In 1861, 11 states tried to leave the United States and form a new country, causing a four-year war. Wars cost a lot of money so the new country, called the Confederate States of America, printed money as a way to pay its bills.

But this money was more like a promise – in technical terms, a “promissory note” – because its certificates were really pledges to give the currency’s holder a specific amount of gold or silver, but only if the Confederacy won the war.

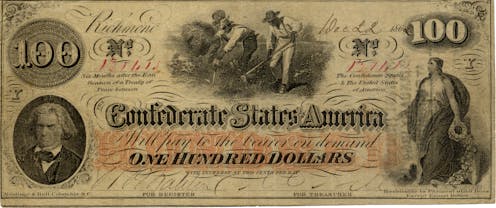

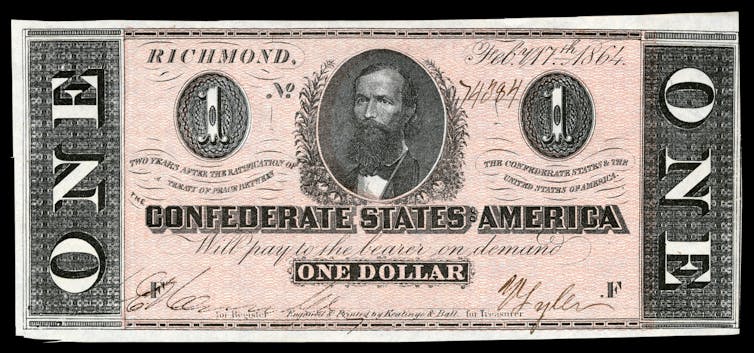

Bills issued earlier in the war said right on them, “Six months after the ratification of a treaty of peace between the Confederate States and the United States, the Confederate States of America will pay” the bill’s amount to the person holding it. Later currency delayed the promised payout until two years after a peace treaty.

The notes were commonly called “graybacks,” after Confederate soldiers, who wore gray uniforms. They bills were decorated with a variety of images, including depictions of mythological gods or goddesses, like the goddess of liberty. Other graybacks bore images of important people in Southern history like George Washington, Andrew Jackson and Jefferson Davis. Some of the bills depicted enslaved Americans working in the fields, or featured pictures of cotton or trains.

But these images often weren’t very good quality, because the Confederacy didn’t have many engravers who could make the detailed plates to print the money.

When the South started losing the war, the value of Confederate money dropped. In addition, prices for food, clothing and other necessities rose because many items were scarce during the war. Graybacks became almost worthless.

In late 1864, a few months before the war’s end, one Confederate dollar was worth just three cents in U.S. currency.

When the Confederate army surrendered in April 1865, graybacks lost any remaining value they might have had. The Confederacy no longer existed, so there was nobody who would exchange its paper money for gold or silver.

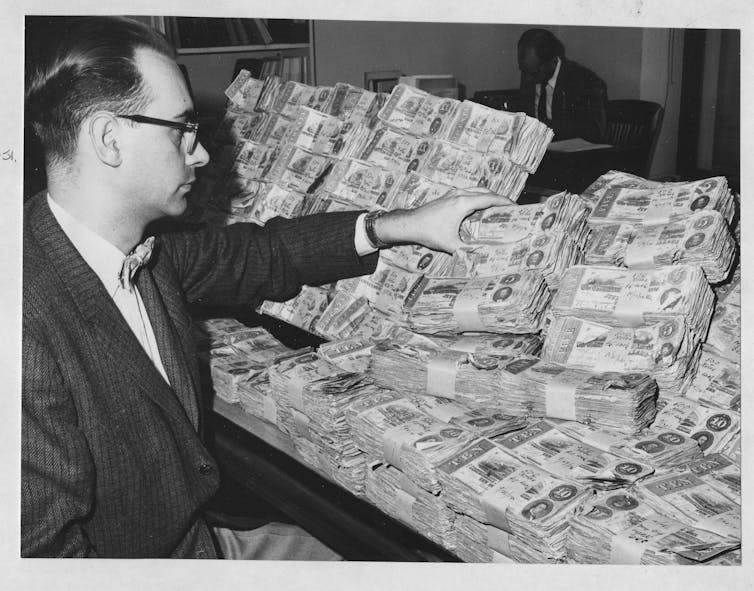

Today, though, Confederate dollars have value as a collectible item. Just like people will pay money to own a Civil War hat or musket, they will pay money to own Confederate money. Some rare Confederate bills are now worth 10 times more than they were in 1861.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.

Robert Gudmestad does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

When US fights in the Middle East, American Muslim students often face discrimination

The war on terror is among the Middle East conflicts that sparked a rise of anti-Muslim and anti-Arab…

How sewage treatment plants could handle food waste, sparing landfills and the climate

Rather than generating climate-warming emissions and wasting nutrients and energy, food waste can become…

Nearly 1 in 3 missing children in the US are Black, driving Pennsylvania and other states to propose

Black children who go missing are often labeled as runaways, which excludes them from the Amber Alert…