All American presidents have made spectacles of themselves – and there’s nothing wrong with that

A president’s persona is always a public act. In that way, Trump's shtick – vulgar man of the people – was not exceptional. And every president has had to invent his version of the role.

After four years of Donald Trump as president, many Americans were sick and tired. They booted him out, with large numbers likely preferring not to hear about him ever again.

And yet, as a historian of the early American republic, I dare say that the man – or rather the personage – has already become a classic. Trump will remain in the public debate for centuries.

Trump’s apparently calculated shows of lack of compassion plus his galloping vulgarity made him into one of the most unpresidential presidents ever.

But while Trump’s vulgarity alienated many, a big chunk of Americans saw it as a show, a choreography aimed at doing away with the hypocrisy of Ivy League-educated liberals, although Trump’s appointees were even more Ivy League than those in other administrations.

As the recent elections demonstrate, large numbers of voters have condoned the former president’s lowbrow attitudes. Vulgarity, for millions, was just a means to an end. It was part of a larger plan, the beginning of a Jacksonian, democratic revolution expected to give a voice to working-class voters who have been overlooked, allegedly smothered by decades of censorship or “leftist political correctness.”

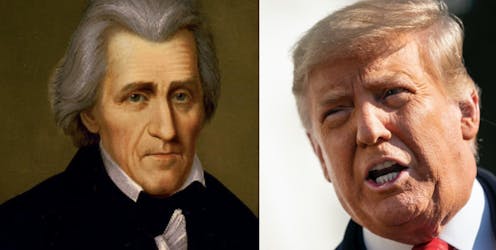

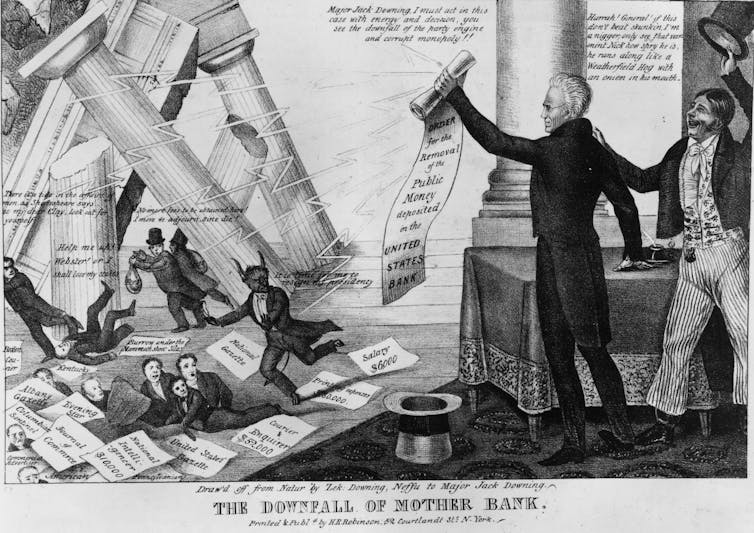

Trump would have loved to emulate the achievements of Andrew Jackson, his idol. Jackson was the president who changed 19th-century America forever. He expanded (male) suffrage, fought against the banks, reshaped federal institutions, and championed territorial expansion – at the expense of Native Americans.

Jackson was also the man who revolutionized the figure of the president. With a penchant for exaggeration, he called for a degree of authenticity in the personage – and it didn’t matter if it was real or pretended.

It’s an American idea that Trump also got perfectly right: Acting out the “man of the people,” with a load of weaknesses and flaws, may well help the president send citizens the message that the supreme office also belongs to them; that the president is like “We the People.”

Alike in style, communication, resentments

In terms of political achievements and successes, Trump is not like Jackson. Personally, the two are also very different: While Trump was steeped in privilege since birth, Jackson was born into a Scots-Irish family of modest means, somewhere along the border between North and South Carolina. And only Jackson was a military hero and a committed nationalist who, despite all flaws, never chased personal interests. No competition.

But there is one area in which the two can compete: Trump is a novel Andrew Jackson in matters of personal style, approach to communication and raids launched against the “liberal elites” – in Jackson’s case, against the two patrician Presidents Adams – John and John Quincy – plus the presidential class known as the “Virginia Dynasty”: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and James Monroe.

Both Jackson and Trump put on stage the same seductive character, the “man of the people.” Like Trump, President Jackson was less than regal. Like Trump, Jackson made deliberate shows of coarseness, profanity and vulgarity in general.

By 1829, the year of his inauguration, the man was a physical wreck. Toothless, his lungs chronically irritated by a bullet he was shot with during a duel, Jackson used to sputter what he called “great quantities of slime.” There’s worse: In a calculated effort to intimidate his enemies and inspire his followers, Jackson would break into terrible fits of shouting, foot-stomping, book-slamming and table-pounding.

And he cursed like a sailor. President Jackson had a pet parrot, Poll. On June 10, 1845, about 3,000 people attended Jackson’s funeral, at the Hermitage, Tennessee. A story goes that Poll was greatly annoyed by the mourners. Jackson’s propensity for swearing must have rubbed off on his pet, because the parrot unexpectedly launched into a blasphemous tirade. Everyone was flabbergasted.

‘Demean himself’

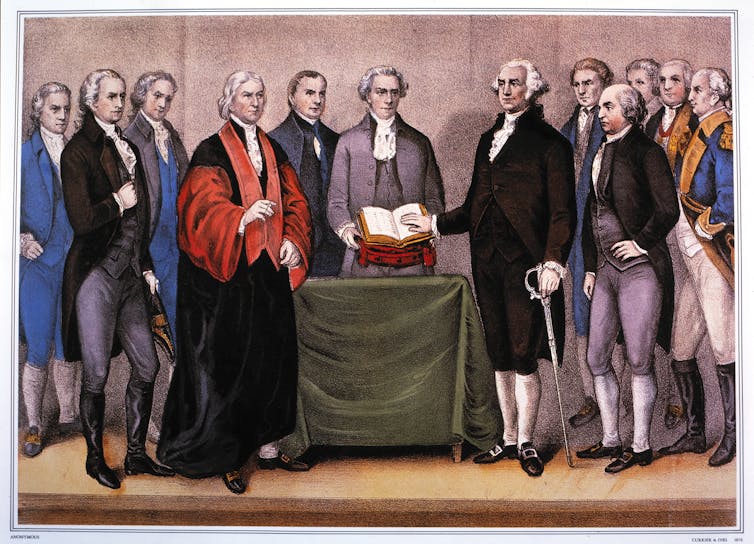

Marking the proper measure of the “regality” of a president is similarly important. For a nation built upon a Constitution, rather than upon hereditary aristocracy, the figure of the president must be unlike any king. And presidents must not be demi-gods or saints either.

When he was sworn in as the new nation’s first president on April 30, 1789, George Washington had no precedent to rely on. Understandably, he was a little bemused. What shall the president be doing? And who is the president, after all? On May 10, Washington wrote to John Adams and asked for his “candid and undisguised opinions” in matter of presidential etiquette and strategies of self-presentation.

An 18th-century elite man, Washington wasn’t tempted by vulgarity, of course. He wasn’t trying to become a “man of the people” himself. He rather feared he could fall into the opposite excess, aristocracy.

“The President,” he wrote to Adams, “can have no object but to demean himself in his public character, in such a manner as to maintain the dignity of Office, without subjecting himself to the imputation of superciliousness or unnecessary reserve.”

‘Persona is a public act’

Washington’s era was different from Jackson’s era, and from our era. But Washington is still right, I believe, and not only to suggest that moderation may be preferred over extremes. Washington is especially right in his claim that the president’s persona is a public act, and does not belong to the individual exclusively.

In terms of institutional procedures, Trump may have done some harm to the office, but he did not and could not destroy the role of the president – the symbolic, inspirational, educational role attached to that office.

The reason is that this role must be reenacted each time. In over 200 years, all presidents, good and bad, couldn’t help asking themselves what the title “President of the United States” entailed, practically. And what piece of theater they were supposed to perform, exactly.

Joe Biden must be asking himself the same question. And he has already provided some answers. Neither an aristocrat nor a pure “man of the people,” he has already presented himself as an empathetic man and a loving, supportive and protective father and grandfather. Biden’s persona, presented in an elderly man with feathery white hair, brings his religious faith to the fore.

The first Catholic president after John F. Kennedy, Biden offers himself as a novel, much-needed American Moses. Are Americans ready for this personage? Will he succeed in connecting with “We the People?”

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]

Maurizio Valsania does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

When GPS lies at sea: How electronic warfare is threatening ships and their crews

In addition to watching out for missile and drone attacks, mariners in conflict zones need to be on…

‘Hamnet’ is making audiences break down in tears – and upending beliefs about male grief

The Oscar-nominated film about Shakespeare’s son explores how men and women mourn differently –…

A successful USDA program that has supported more than 533,000 affordable rental homes in rural Amer

Hundreds of thousands of rural families could lose their affordable homes as mortgages the program supported…