The pandemic has affected millions with other illnesses – here's how it affected a health professor'

People with eating disorders often struggle with staying in control. For many, the pandemic took away control. A health scholar shares her story of how that loss of control affected her bulimia.

Control. What does it mean to lose control? For someone who has spent nearly half their life battling an eating disorder, losing control is about an extremely heightened awareness of numbers. Numbers I believe I can control.

Because I have an acute need for control, this pandemic drove me to focus on numbers that I spent years in therapy training my brain not to obsess over. What is my weight? How many minutes have I exercised today? When is the next time I can eat? How many calories have I consumed? These are numbers that I believe I can control when other aspects of life seem unmanageable.

As a public health expert focusing on food and nutrition policy, I assumed that the coronavirus would impact our country heavily. But I was not mentally prepared for the level of destruction that would suffocate our communities. And I was not prepared for how it would affect me.

An ongoing battle

The pandemic has altered all of our lives, most particularly the families and friends of those who have died and those who are recovering from COVID-19. I understand that my suffering is nowhere near as serious as theirs. I recognize my privilege as a white, fully employed woman. My experience leads me to wonder how people with fewer resources, or without jobs and access to health care, have fared and will continue to fare.

I am one of millions whose mental health has been impacted by this pandemic. My mental health struggle revolves around control – and manifests itself in my efforts to control something no one else can – my body. Even though I physically suffered from bulimia for a decade, emotionally I will always be on the path to recovery. I will never fully recover from my battle with bulimia. And feeling frozen in time, not remembering what month or day it is, this pandemic has been a stark reminder that recovery is a process.

Bulimia is a cycle of eating large amounts of food and compensatory behaviors designed to reverse the effects of binging. My bulimia involves strict dieting, binging at dinner, and then self-induced vomiting to rid myself of calories. When engaging in disordered eating, I believe I’m in control of the situation. In reality, the exact moment I’ve acted on an impulse is when I’ve lost control.

In college, I remember sitting in a child psychology class on the day we focused on eating disorders. I glanced at the diagnostic criteria for bulimia and realized the words on the page were describing me. Until that point, I had convinced myself that my disordered eating would stop once I reached my “weight goal.” It wasn’t until years later that I acknowledged I could never reach my goal, because I continued to change it.

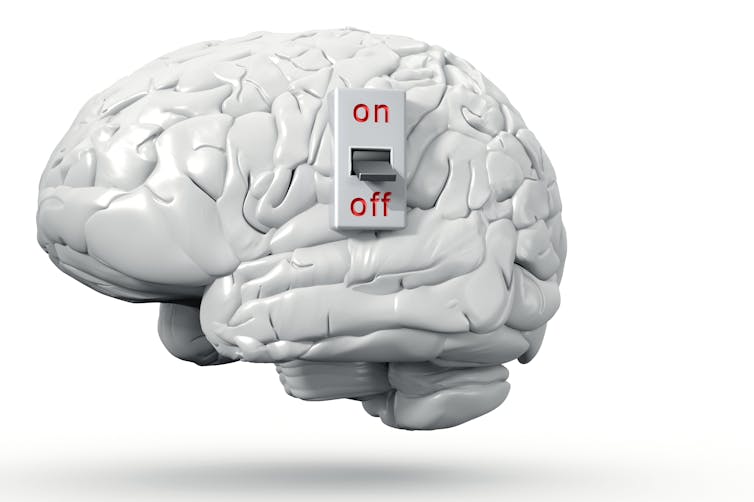

For someone who is fueled by tremendous willpower, facing an impossible goal usually doesn’t end well. Once I recognized that I couldn’t just turn my bulimia “on” and “off,” it was too late. That “switch” in my brain that I thought I could control no longer worked because it never existed.

Pandemic tipping point

When I started working remotely in March, I went from traveling sometimes several times a week to working alone in my house. I became anxious, agitated and frustrated with all the uncertainty. Like many people during this pandemic, I craved some sense of normalcy.

Whereas social interaction is a breeding ground for COVID-19, social isolation is where eating disorders thrive. Feeling frustrated with the world around me, I resorted to focusing on what I thought I could control – my body.

In April, only a few weeks into working remotely from home, I began subjecting my body to the humiliating act of purging the food I consumed. Maybe because I’m older than when I first became bulimic, the practice of exercising in the morning, fasting all day, and sneaking around after dinner was and is physically and emotionally more draining. For every day I kept my relapse hidden from my spouse, I plunged deeper into an illness that was spiraling out of control.

In absence of a national strategy to address the pandemic, I began piling on rules around my daily routine. Just like the unattainable weight goals I set in college, I began setting unrealistic rules that my body could not follow.

Returning to recovery

After two months of quarantine, and as more data about COVID-19 emerged, I saw a very bleak picture of my future. I realized I didn’t have the energy to fight for “control” over my body. Once I accepted that my body could not endure these actions long-term (again), coupled with the fact that COVID-19 was not going anywhere, I decided I needed a plan.

The first step was sharing my relapse with my spouse – which was harder the second time around. I have a much stronger sense of shame now, because I should “know better.” I should know not to engage in this behavior. But just because an expert knows better doesn’t make it any easier – especially during a pandemic.

Next, I focused on redirecting my obsession with numbers on a scale. I limited the amount of time I spent comparing myself to others on social media. I spoke more openly about my impulses and urges with my spouse. I spent as many hours outside as possible. I worked in my garden. With dirt under my fingernails and sweat dripping down my face, I proudly watched my daffodils, irises, peonies and roses bloom through the seasons. And then there was the satisfaction of weeding. Ripping out invasive plants – digging down to the root and purging them from my garden. Just like my bulimia, if the root isn’t addressed – it will return with a vengeance.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

I am not a mental health professional, but I hope to reach people who might be tempted to experiment with disordered eating. If I can reach those who may be thinking about it as a means to manage weight during a time when it’s hard to manage life, I can show them this is a path you never want to take. This is a path that once you go down, you can never go back. You may be able to walk on the side, but that temptation will always be there, on the edge of your every step. And when you finally find your path to recovery, a pandemic might hit. And like me, you might realize just how easy it is to stumble and fall.

Lastly, I hope this might be a warning to our country’s leaders. With 5 million COVID-19 cases and more than 161,000 deaths, the country can’t neglect the millions of people who are fighting a wave of mental health issues. Please don’t let this spin out of control. People have stumbled and some have fallen during this pandemic. Our country needs a comprehensive plan for addressing the inevitable mental health crisis.

If you or a loved one needs help with managing an eating disorder, the National Eating Disorders Association can provide resources.

Lindsey Haynes-Maslow does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Living in space can change where your brain sits in your skull – new research

These changes aren’t permanent – the brain goes gradually back to normal after coming back to Earth.…

Green or not, US energy future depends on Native nations

Native American lands contain 30% of the nation’s coal, 50% of its uranium and 20% of its natural…

The rise of ‘Merzoni’: How an alliance between Germany’s and Italy’s leaders is reshaping Europe

The center of gravity in Europe is increasingly aligning along a Rome-Berlin axis.