Contact tracing's long, turbulent history holds lessons for COVID-19

Trust in the confidentiality of contact tracing broke down during the AIDS epidemic. Today, it's faltering again.

To get the COVID-19 pandemic under control and keep it from flaring up again, contact tracing is critical, but persuading everyone who tests positive to share where they’ve been and with whom relies on trust and cooperation.

Contact tracing’s long, contested history shows how easily both can be shattered.

Looking back at the reasons for resistance to contact tracing as the U.S. struggled to contain epidemics in the past can help us understand the first signs of pushback against contact tracing in the COVID-19 response, as well as the public health consequences.

Reporting by code rather than name – sometimes

The goal of contact tracing is to break the chain of transmission by finding everyone an infected person has been in contact with, testing them if they were exposed and isolating them if they, too, are infected.

Unlike social distancing, which had not been used on such a wide scope and scale since the influenza pandemic of 1918, contact tracing has been a staple of infectious disease control since the 1920s.

At that time, doctors were reluctant to report the names of patients with any condition to health departments. They feared that health departments would “steal” their patients or breach personal information disclosed in a confidential clinical relationship.

Syphilis changed things. Because sexually transmitted diseases were highly stigmatized, health officials and physicians struck a compromise. “Upstanding” patients with conditions like syphilis need not be reported by name to state health departments, only by a code. Yet “recalcitrant” patients – poor or marginalized patients who might not keep all doctor’s appointments – were typically reported to health departments by name so health officials could manage them. Prostitutes were often jailed to contain disease spread.

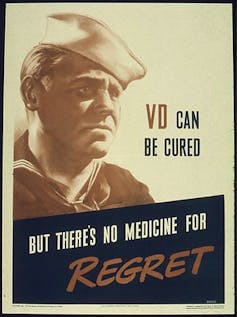

By the time penicillin was developed in the 1940s, the country faced an imperative to “find the missing million” people who were infected and spreading the disease. Health officials would test and treat infected people’s contacts in order to “stamp out VD.” In this context, reporting patients by code instead of by name was no longer conceivable given the scope and scale of the crisis.

In the 1960s, when rates of syphilis soared again, physicians were required to report cases to health departments, which had the manpower to interview patients and follow up all contacts. Physicians had long exercised an ethical duty to warn sexual contacts, but as a health department practice, contact tracing fundamentally relied on the cooperation of patients. Confidentiality, therefore, became standard practice. Investigators would never confirm the name of the patient to a contact, even if it could only be one person, like a spouse.

AIDS: When patient trust broke down

During the early years of the AIDS epidemic, trust in the confidentiality of contact tracing broke down.

Homosexuality or sodomy was still illegal in several states in the mid-1980s, and compiling lists of the names of gay men and their sexual contacts felt not only stigmatizing but risky.

With no effective treatment for AIDS, activists challenged the benefit of taking that risk with contact tracing. One activist compared name-based reporting and contact tracing to the Holocaust: “The road to the gas chamber began with lists in Weimar, Germany.”

Some of that fear was stoked by a California Supreme Court decision that psychiatrists had a duty to warn if they believed one of their patients might harm another person. As the judges in the case, Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California, famously wrote, “The protective privilege ends where the public peril begins.”

For the gay community, as well as for people who injected drugs, the fear was not simply that sexuality and sexual behavior might be inadvertently disclosed in the process of contract tracing, but actively disclosed. Indeed, despite his cooperation, this is exactly what happened in the case of NuShawn Williams – a New York state man who reported relationships with dozens if not hundreds of sexual partners, including girls under the age of 16. Health departments renamed the process “partner notification.”

Technology raises new privacy concerns

Today, in the era of COVID-19, citizens and lawmakers alike have expressed profound concerns about the kind of sweeping intrusion that new, technology-driven forms of contact tracing advanced by Apple and Google could bring.

A group that calls itself Free Ohio Now, while open to traditional contact tracing involving individuals working under the auspices of the health department, is alarmed by the prospect of electronic contact tracing. Member Tom Hach explained, “The door becomes wide open if you use electronic, it’s basically electronic surveillance, and that can be used for many things down the road that this particular application can broadened in the future.”

Unlike China’s apps, Apple and Google plan to rely on U.S. mobile users’ consent. The dilemma for public health officials is that if not enough people agree to use the apps, the apps lose their value for containing the virus’s spread.

Ultimately, Americans face a trade-off between public health and privacy. For these reasons, health departments around the nation have been hiring thousands of human contact tracers who work by phone and uphold confidentiality.

Yet in Texas, a state hit hard by the latest surge in cases, even those traditional methods are drawing fire, echoing the concerns voiced in the early years of the AIDS epidemic. Grant Byum, explaining the position of his group Texans Against Contract Tracing, said COVID-19 may be real but “it’s just not been a hugely significant issue as far as deaths and we just think it’s extreme overkill.”

Drawing the line between ‘cops’ and ‘docs’

In a context in which some people continue to claim COVID-19 is a hoax, in which masks are contested and in which social distancing is challenged as a violation of individual rights, contact tracing is at risk of politicization.

Minnesota Public Safety Commissioner John Harrington sparked more fears when he used the term “contact tracing” to describe how police track down suspects. The remark stirred unfounded concerns that police could gain access to COVID-19 case reports to determine who had attended protests over police brutality.

There’s never been a more important time to draw a bright line between cops and docs when it comes to the health of populations hit hardest by COVID-19. But there are times when public health relies on the legal system in order to fulfill its mission. In New York’s Rockland County, health officials resorted to subpoenas to compel individuals who attended a party associated with an outbreak to cooperate with contact tracers.

Contract tracing is a key to helping states avoid a return to sweeping social distancing measures like stay-at-home orders and business closures. Trust that one’s name and medical information will be kept confidential is core to its success. Without that trust, even individuals who might want to help identify potential contacts may feel silence is safer.

But contact tracing also relies on speed. We not only need more contract tracers in the U.S., we need more cooperation. If too many individuals refuse to participate, public health risks losing one of the single best means of halting the resurgence of COVID-19.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Amy Lauren Fairchild has received funding from NIH and NSF.

Ronald Bayer has received funding from NIH and NSF.

Lawrence O. Gostin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Crowdfunded generosity isn’t taxable – but IRS regulations haven’t kept up with the growth of mutual

Some Americans are discovering that monetary help they received from friends, neighbors or even strangers…

What is Bluetooth and how does it work?

Did you know that your wireless earbuds contain a tiny radio transmitter?

How transparent policies can protect Florida school libraries amid efforts to ban books

Well-designed school library policies make space for community feedback while preserving intellectual…