Days with both extreme heat and extreme air pollution are becoming more common – which can't be a go

In South Asia, days with both extreme heat and extreme pollution are expected to increase 175% by 2050. Separately, the health effects are bad; together they will likely be worse.

The Research Brief is a short take on interesting academic work.

The big idea

Days of extreme high heat and extreme air pollution are both increasing worldwide. Last November, New Delhi experienced a week of the worst air pollution in human history. The entire city shut down and planes couldn’t see well enough to land. Not long before that, Western Europe was slammed with two record-breaking heatwaves that caused the deaths of nearly 1,500 people.

Days of extreme heat and extreme pollution do not often overlap, but our two teams at Texas A&M wanted to see if the number of these double extreme days was increasing and explore what the health risks of that might be.

To test this, we used a computer model to look at the co-occurrence of extreme heat and extreme air pollution in South Asia. The model incorporated trends in greenhouse gas and air pollution emissions from industrial and residential sources, population growth, migration trends and even how air pollution is affected by weather, terrain and nearby oceans.

We predict that the frequency of days with both extreme heat and pollution – and the number of people that will be affected by those days – could massively increase by 2050.

We focused on South Asia because it’s already a climate change hot spot and its population is projected to increase from 1.5 billion today to 2 billion by 2050. Under a worst-case climate change scenario and with little reduction in CO2 and other pollutants, days with both extreme heat and extreme pollution would increase in frequency by 175% in the region, resulting in roughly 78 days a year with those double whammy conditions.

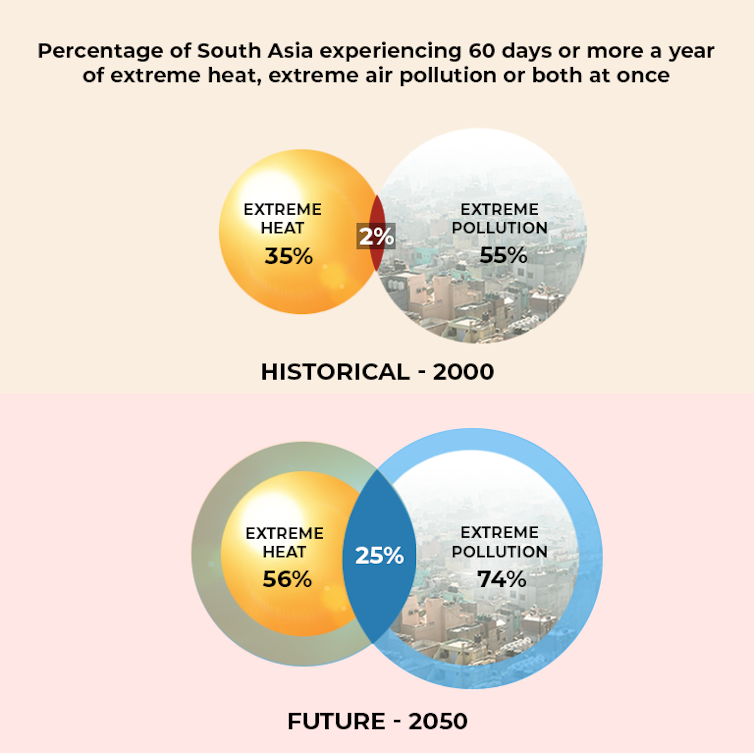

Additionally, the amount of land that would experience this double threat for 60 days or more a year would increase tenfold from 2000 to 2050 – from 2% to more than 25% of all of South Asia. This will also lead to more than 52% of the population being exposed to more than 60 days of this double hazard.

Why it matters

Both extreme heat and air pollution have severe negative effects on the human body.

Extreme heat increases the likelihood of heat exhaustion and heat stroke, but can also worsen chronic ailments such as heart disease. As part of an effort to better understand how extreme heat affects mortality rates, we are currently studying the health effects of heat extremes here in Texas.

Air pollution is known to lead to asthma, heart disease, pregnancy complications and other severe health effects.

So what happens when a person experiences both at the same time?

Scientists know that when a person experiences air pollution in addition to another simultaneous stressor, they become more susceptible to both. This has been shown for combinations such as air pollution and smoking, as well as air pollution and COVID-19.

It is hard to say exactly what effect a prolonged exposure to the double threats of heat and air pollution would have on human health as there have only been a few cases studies looking at the combined effects of both. The results, though sparse, do suggest that more people die when the two conditions co-occur.

What still isn’t known

The full health effects from a combination of extreme heat and extreme pollution are largely unknown, especially in many developing nations where studies haven’t been done and the extremes are expected to get more severe. Billions of people are expected to experience these conditions in the coming decades, but researchers know little about what the risks are.

Which populations – both demographically and in terms of chronic diseases – are most at risk? Just how dangerous are these double extreme days to human health? Where are the most at-risk populations?

It is thus important to develop an empirical understanding of the relationship between health outcomes and multiple environmental stressors like heat and air quality.

What’s next

Learning who is most at risk is important, but taking preventative measures, everyone together, should also be considered.

Using our models, we found that reducing carbon dioxide and non-CO2 air pollutant emissions – even by a moderate amount far less than what would be required to meet the 2 degrees Celsius target in the Paris agreement – would prevent the most severe outcomes.

Even under a very moderate emission reduction scenario called RCP6.0 – where emissions peak in 2060 – the frequency of double extreme days would increase by only 58% by 2050, compared to the 175% we are headed for. The population and land area to experience extended exposure to this hazard would be less than half of what was projected in the business-as-usual scenario.

These increases are still nothing to look forward to, but they show that mitigation efforts can make a big difference. In our view, the world needs to act swiftly and, for example, seize the opportunity of current economic recovery to invest in greener energy. Our future generations do not deserve a dirty, hot future.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Yangyang Xu receives funding from National Science Foundation.

Xiaohui Xu does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

Violent aftermath of Mexico’s ‘El Mencho’ killing follows pattern of other high-profile cartel hits

Members of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel have set up roadblocks and attacked property and security…

What is Bluetooth and how does it work?

Did you know that your wireless earbuds contain a tiny radio transmitter?

Picky eating starts in the womb – a nutritional neuroscientist explains how to expand your child’s p

While genes do influence some food preferences, positive experiences can help make new tastes easier…