When will there be a coronavirus vaccine? 5 questions answered

One of the dangers of the new coronavirus is that there is no treatment – and no vaccine. But researchers had already been at work on vaccines for close-related viruses.

Editor’s note: The coronavirus that started in Wuhan has sickened more than 4,000 people and killed at least 100 in China as of Jan. 27, 2020. Thailand and Hong Kong each have reported eight confirmed cases, and five people in the U.S. have been diagnosed with the illness. People are hoping for a vaccine to slow the spread of the disease.

Is there a vaccine under development for the coronavirus?

Work has begun at multiple organizations, including the National Institutes of Health, to develop a vaccine for this new strain of coronavirus, known among scientists as 2019-nCoV.

Scientists are just getting started working, but their vaccine development strategy will benefit both from work that has been done on closely related viruses, such as SARS and MERS, as well as advances that have been made in vaccine technologies, such as nucleic acid vaccines, which are DNA- and RNA-based vaccines that produce the vaccine antigen in your own body.

Was work underway on this particular strain?

No, but work was ongoing for other closely related coronaviruses that have caused severe disease in humans, namely MERS and SARS. Scientists had not been concerned about this particular strain, as we did not know that it existed and could cause disease in humans until it started causing this outbreak.

How do scientists know when to work on a vaccine for a coronavirus?

Work on vaccines for severe coronaviruses has historically begun once the viruses start infecting humans.

Given that this is the third major outbreak of a new coronavirus that we have had in the past two decades and also given the severity of disease caused by these viruses, we should consider investing in the development of a vaccine that would be broadly protective against these viruses.

What does this work involve, and when might we actually have a vaccine?

This work involves designing the vaccine constructs – for example, producing the right target antigens, viral proteins that are targeted by the immune system, followed by testing in animal models to show that they are protective and safe.

Once safety and efficacy are established, vaccines can advance into clinical trials in humans. If the vaccines induce the expected immune response and protection and are found safe, they can be mass produced for vaccination of the population.

Currently, we lack virus isolates – or samples of the virus – to test the vaccines against. We also lack antibodies to make sure the vaccine is in good shape. We need the virus in order to test if the immune response induced by the vaccine works. Also, we need to establish what animals to test the vaccine on. That potentially could include mice and nonhuman primates.

Vaccine development will likely take months.

Can humans ever be safe from these types of outbreaks?

We expect that these types of outbreaks will occur for the foreseeable future in irregular intervals.

To try to prevent large outbreaks and pandemics, we need to improve surveillance in both humans and animals worldwide as well as invest in risk assessment, allowing scientists to evaluate the potential threat to human health from the virus, for detected viruses.

We believe that global action is needed to invest in novel vaccine approaches that can be employed quickly whenever a new virus like the current coronavirus – and also viruses similar to Zika, Ebola or influenza – emerges. Currently, responses to emerging pathogens are mostly reactive, meaning they start after the outbreak happens. We need a more proactive approach supported by continuous funding.

Florian Krammer receives funding from NIAID, DoD and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, including for work on influenza virus vaccines. He is also named as inventor of technology in the field of human influenza vaccines and is a named co-inventor on patents on technology to develop chimeric HA-based universal influenza virus vaccines.

Aubree Gordon does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

As the Oscars approach, Hollywood grapples with AI’s growing influence on filmmaking

AI tools can now generate movie scenes, resurrect lost footage and replace entry-level jobs – forcing…

While the US government is investigating unidentified anomalous phenomena, academic researchers stud

Surveys have found that researchers studying UAPs can face pushback from mentors and colleagues, even…

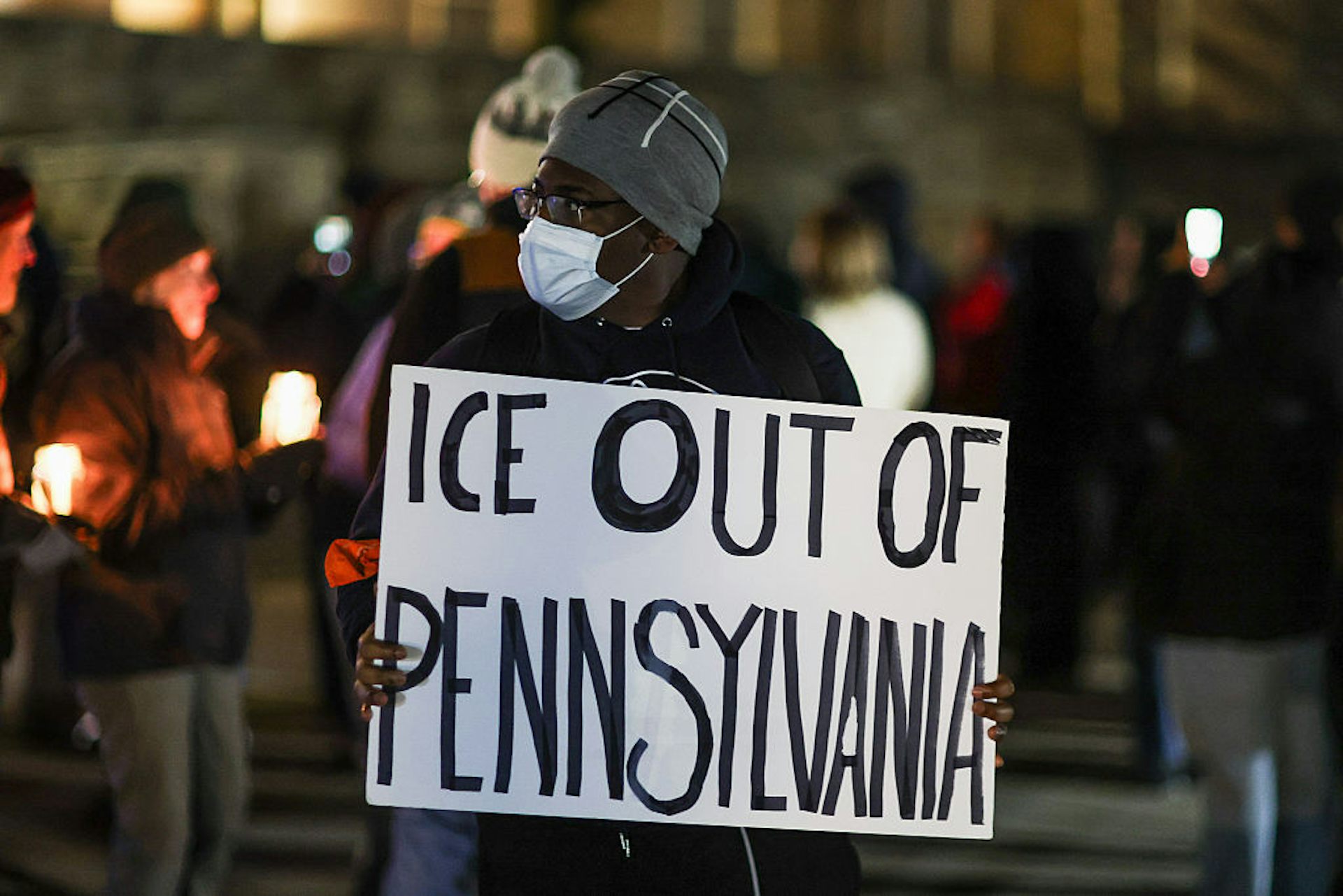

ICE buys $87M warehouse in Pennsylvania − can local officials block a detention facility?

After the government acquired a warehouse in PA to expand ICE operations, questions are mounting about…