Snacks after youth sports add more calories than kids burn while playing, study says

Youth sports are a great way for kids to be active, but a recent study showed that after-sports snacks, on average, had 43 more calories than the amount burned during the activity.

Youth sports leagues are a great way for children to get physical activity, develop teamwork and create friendships. Research has shown that youth who participate in sports leagues are eight times as likely to be active in their early 20s than those who don’t participate.

This is good news for the more than half of American youth ages 6 to 12 who participated in a team sport in 2017, with baseball, basketball and soccer being the most popular. But our recent research showed that snacks after youth sports games contained more calories than the amount kids burned.

Both of us are faculty members in public health who study childhood obesity. Most of Jay’s work is in physical activity and looks at the effect of the environment on health, including parks and city design. Lori specializes in the food environment and has examined the effects of school breakfast and salad bar programs on student nutrition.

Snacks and youth sports

Our interest in this issue started years ago. When I (Jay) was growing up in the 1980s, I loved playing in youth basketball and baseball leagues. Twenty-five years later, I was excited to enroll my sons in youth sports, including basketball, soccer and flag football.

However, from the first team meeting, something was different. The coach passed around a sign-up sheet to bring a grab-and-go snack for the team. I was surprised by this. When I was growing up, the only sport that had a snack was soccer, and that was oranges and water at half time. Why did these kids need a snack at 2 in the afternoon?

I signed up later in the season to see what the other parents were bringing as snacks. I was even more surprised when the snack turned out to be a hot dog in a bun, a bag of chips, a cookie and a sports drink! My son had just eaten lunch a couple of hours before and had only played for 20 minutes.

I thought to myself: They have got to be consuming more calories than they expended. A few years later, Lori Spruance and I decided to test this and find out if it was true.

Testing our ideas

Lori and her team went out between April and October of 2018 and observed 189 youth sports games for children in the third and fourth grade. The games included soccer, baseball, softball and flag football, and both mixed-gender and single-gender leagues.

To measure calorie expenditure, we used a highly valid and reliable systematic observation tool to assess the duration and intensity of children’s physical activity during the game. The researchers also assessed the calorie content of the food provided, either through the packaging or by measuring the amount of food served.

We found that on average children got 27 minutes of physical activity per game and burned about 170 calories. We were not surprised to find that children playing soccer were the most active, and softball players were the least active. At four out of five games, or 78%, parents served a post-game snack.

When a snack was served, it averaged 213 calories – on average, 43 more calories than the children had expended playing the sport. The most common snacks were baked goods, such as brownies, cookies and cake, followed by fruit snacks, crackers and chips. We were even more disturbed that the average amount of sugar provided was 26.4 grams, exceeding the American Heart Association’s recommendation of 25 grams of sugar per day.

Easy ways to make some changes

We looked at the findings to try to develop a low-cost intervention to help change these effects. Beverages stood out as a major contributor of sugar. In the 145 games where a beverage was served, soda, fruit drinks and sports drinks were served over 85% of the time. Water (3%), milk (1%) and 100% fruit juice (8%) were almost never served. Sugar from drinks (18.3 grams) per serving exceeded sugar from snacks (12.3 grams).

Before the next sport’s season, we developed a one-page fact sheet on smart snacks for your athlete for teams that choose to provide a snack. It recommended water as the drink of choice and small healthy snacks, including mixed nuts, fresh fruit, string cheese, dried fruit and granola bars. These fact sheets were emailed to parents and posted on the local parks and recreation website prior to the season, and researchers came back during the season to see if any changes were made.

Our preliminary results show that the information provided made a difference. We found that 16% of the snacks in the second season included water instead of a sugary beverage; sugary beverage offerings dropped from almost 90% to 80%; and fruits and vegetables increased from 3% to 15%, with an overall drop of 20 calories per game.

These changes appeared to be an easy way for parents to make the smart choice and provide a healthier alternative for their children.

Although 43 calories may not seem like a lot, if a child plays two games a week across 50 weeks this can add up to 4,000 calories or more than a pound of weight per year.

Little changes can make a big difference in promoting healthy body weights in our children. So when your children are playing sports, we recommend making the healthy choice and choosing water, fruits and vegetables and a healthy protein source too, like nuts.

[ Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter. ]

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

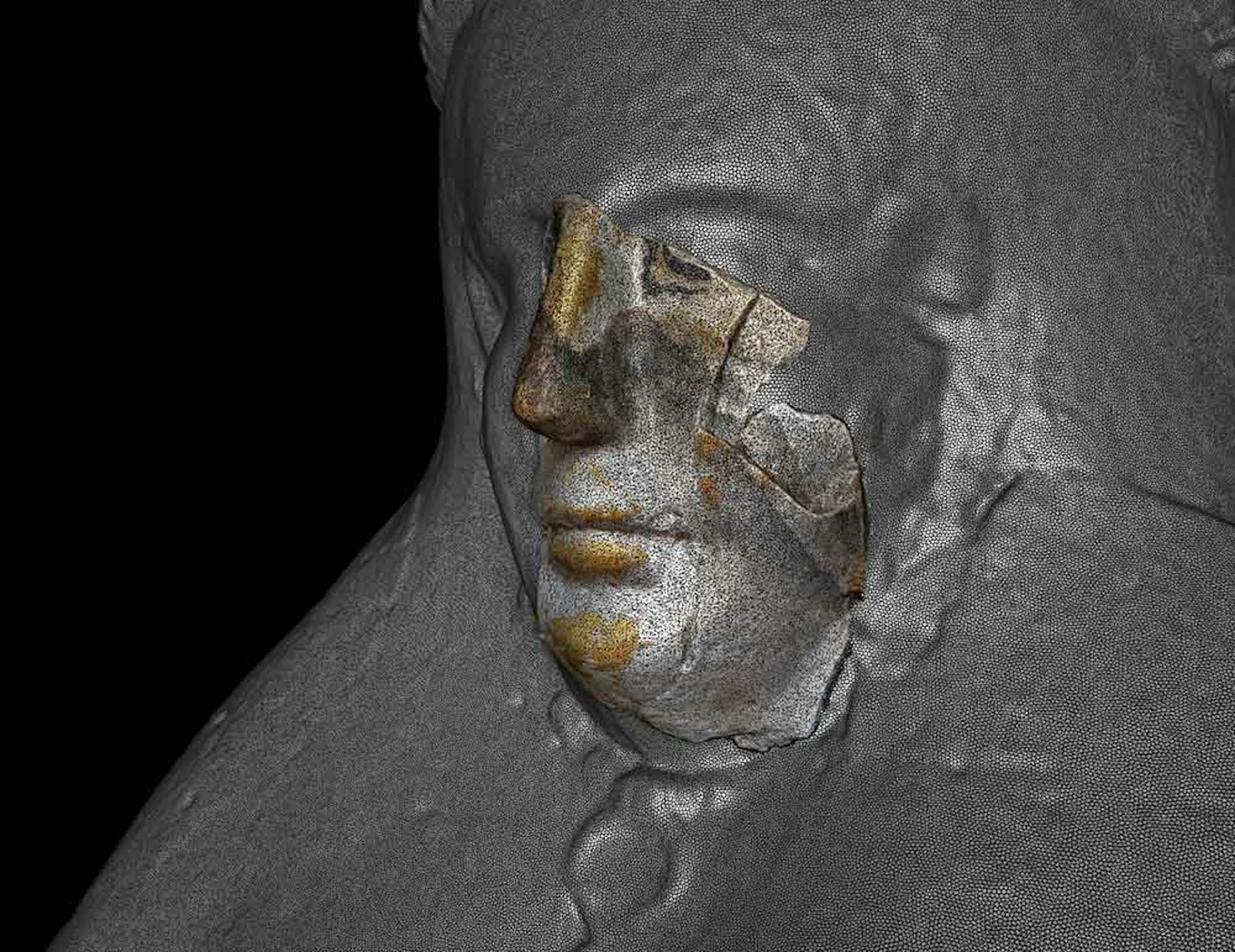

3D scanning and shape analysis help archaeologists connect objects across space and time to recover

Digital tools allow archaeologists to identify similarities between fragments and artifacts and potentially…

The intensity and perfectionism that drive Olympic athletes also put them at high risk for eating di

Athletes in sports where weight and body image come into play, such as figure skating and wrestling,…

Are women board members risk averse or agents of innovation? It’s complicated, new research shows

The effect of women board members on patent activity hinges on whether the company is meeting performance…