As rural Americans struggle for health care access, insurers may be making things worse

Americans who live in rural parts of the country have fewer doctors, specialists and hospitals than those who live in cities. It also appears that insurers are working against them.

Living in rural America certainly comes with a number of benefits. There is less crime, access to the outdoors, and lower costs of living.

Yet, not everything is rosy outside the city limits. Rural communities face growing infrastructure problems like decaying water systems. And they have more limited access to amenities ranging from grocery stores to movie theaters, lower quality schools, and less access to high-speed internet.

Yet perhaps most daunting are the tremendous health disparities rural Americans face, in terms of both their own health and accessing care.

As a number of my recent studies indicate, these disparities may be exacerbated by insurance carriers and the networks they put together for their consumers.

A sick system that’s getting worse

At the turn of the last century, cities were known to be cesspools rampant with disease. Much has changed since then. Today, health care disparities between urban and rural America have indeed reversed. And they are growing wider.

Part of the problem is demographic. Over the last several decades, many rural areas have lost a large share of their residents. In many areas, the young are moving away, leaving an aging population behind.

Besides being older, those staying behind are poorer and have lower levels of education. To make things worse, they are also more likely to be uninsured. And they tend to be sicker, exhibiting higher rates of cancer, heart disease, stroke and chronic lower respiratory disease. It comes as no surprise that their life expectancy is generally lower as well.

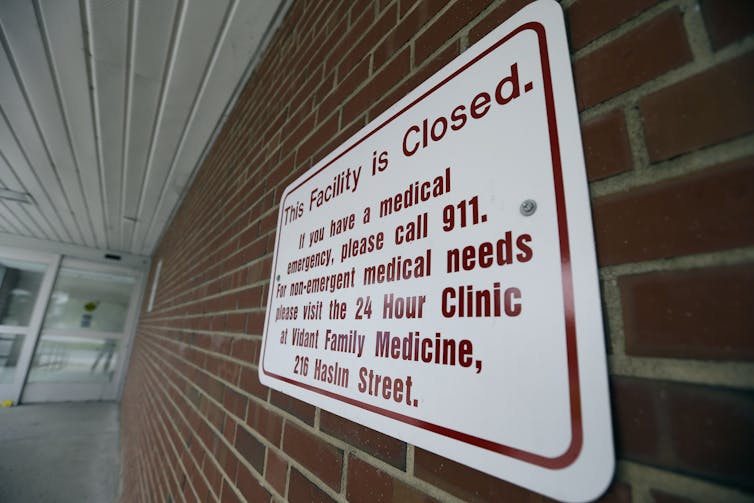

The demographic challenges are made worse by the limitations posed by the health care system. For one, rural areas are experiencing tremendous health care provider shortages. Access is often particularly limited for specialty care. But much more mundane health care services that most of us take for granted, like hospitals – including public hospitals and maternity wards – are also affected.

Politics have made rural access challenges worse in many places. Partisan opposition to the Affordable Care Act has led many states with large rural populations, like Texas and Kansas, to refuse to expand their Medicaid programs or support enrollment in Affordable Care Act marketplaces. This stance is particularly damaging because the program provides a crucial lifeline to rural providers.

A stark divide

Rural communities across the country face tremendous health care access issues. And as recent study my colleagues and I did of access to cardiologists, endocrinologists, OB-GYNs and pediatricians shows, insurance plans may further complicate the issue.

Focusing on California, we compared access between plans sold under the Affordable Care Act and commercially available plans. We also made comparisons to a hypothetical plan that included all of the state’s providers. In theory, this would be the plan available to consumers under various Medicare-for-All proposals.

Overall, we found that consumers living in large metropolitan areas faced only very limited access challenges. However, as distance from cities increased, access worsened significantly. Consumers had fewer providers to choose from, and had to travel further to see them.

One of our starkest findings was the existence of what we called “artificial provider deserts” – areas where providers are practicing and seeing patients, but insurance carriers do not include any of them in their networks. Without access to local providers, some rural residents are forced to travel 120 miles or more to reach in-network care.

Our findings hold for both Affordable Care Act plans and those commercially available, which fared only slightly better.

The problems we found in this study extend well past plans sold on the Affordable Care Act marketplaces. Two of my other studies found similar, if not worse problems, for rural consumers of Medicare Advantage plans in New York and California.

More protections for rural Americans

There are many reasons for the growing disparities between urban and rural America. Many of these aren’t always easily or quickly remedied through government intervention. Indeed, some may be inherent to living outside of metropolitan areas.

Yet when it comes to health care access, our recent work indicates that decisions by insurance carriers may further worsen the situation. Conceivably, insurers may limit access to providers to push sicker populations to enroll with other insurers.

However, the fault may not exclusively lie with insurers. Rural providers may also demand large fees to enter into contracts with insurers, leading insurers to exclude them from their networks.

While regulating provider networks comes with a slew of challenges, it seems apparent to me that our current approach is not working for Rural America. It is time to rethink how we provide and regulate health care access to millions of Americans living in rural areas.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend. ]

Simon F. Haeder is a Fellow in the Interdisciplinary Research Leaders Program, a national leadership development program supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to equip teams of researchers and community partners in applying research to solve real community problems.

Read These Next

Massive US attacks on Iran unlikely to produce regime change in Tehran

President Trump has appealed to Iranians to topple their government, but a popular uprising is unlikely…

Cuba’s speedboat shootout recalls long history of exile groups engaged in covert ops aimed at regime

From the 1960s onward, dissident Cubans in exile have sought to undermine the government in Havana −…

Drug company ads are easy to blame for misleading patients and raising costs, but research shows the

Officials and policymakers say direct-to-consumer drug advertising encourages patients to seek treatments…